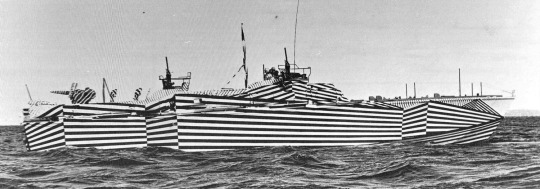

Photograph of WW1 Dazzel Ships at sea.

Camouflage and its part in WW1 has a curious and quaint history. Most people know of the dazzle ships and how the painter Norman Wilkinson found that painting the ships not to fit in made them harder to target by the enemy. But other areas of WW1 where more subtle.

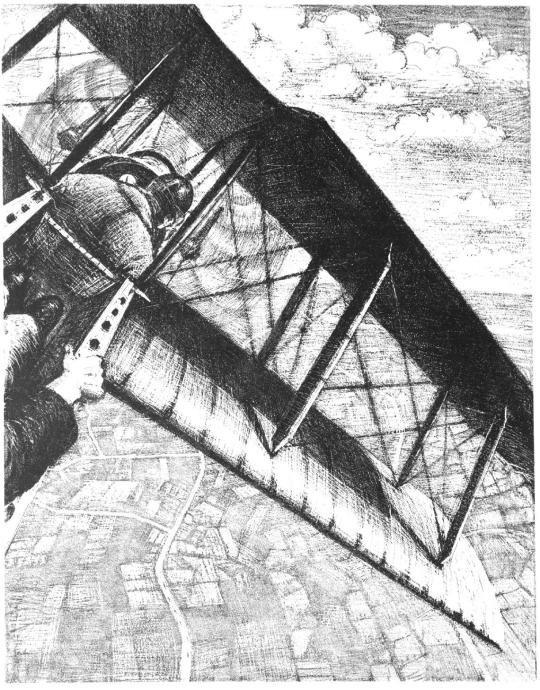

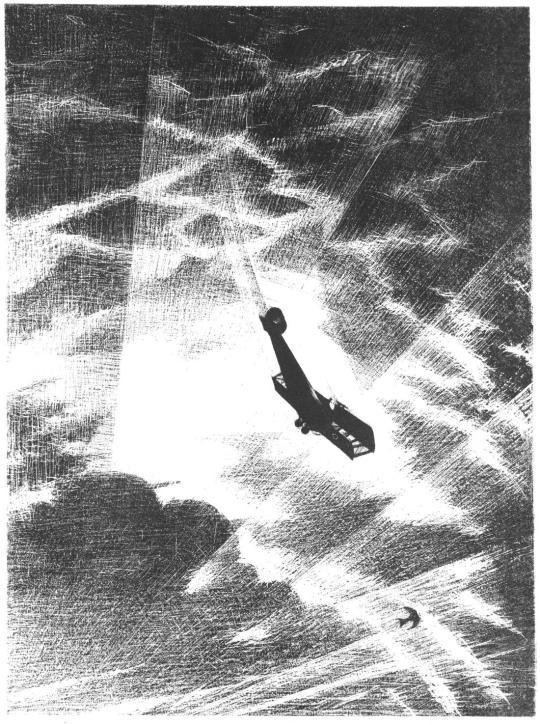

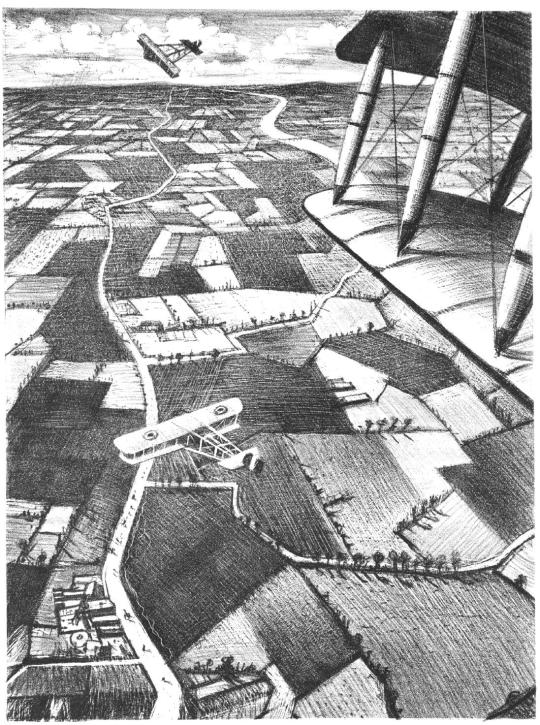

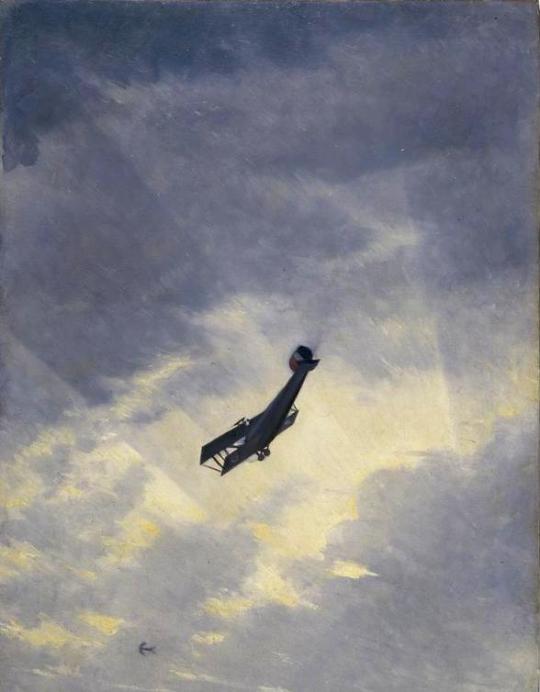

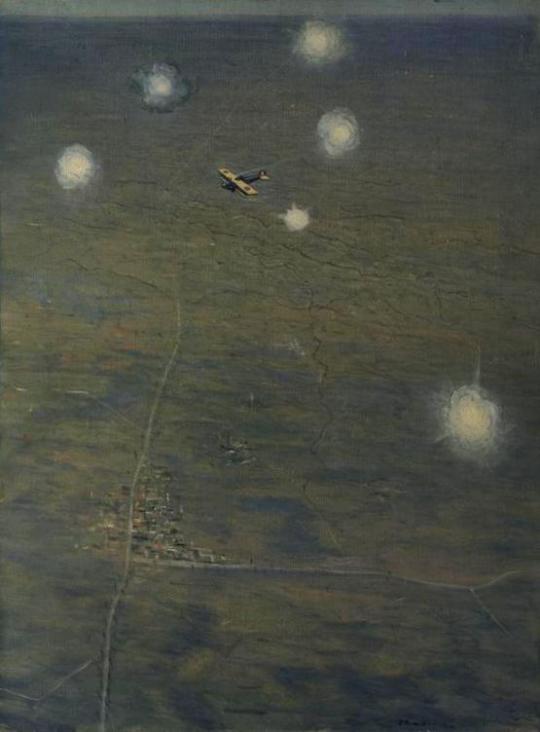

Leon Underwood – Looking Toward Ardregne, 1917

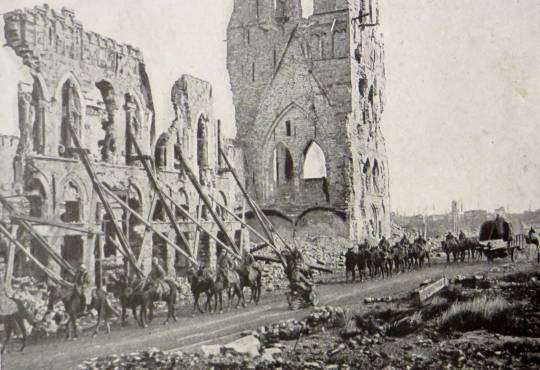

It was another artist, Leon Underwood who worked with Solomon J Solomon on making a fake tree Observation post. With so much of the war being fixed with both sides in trenches, any height was an advantage to see what the enemy was up to. You can see how trees ended up looking after months of shell-fire from the Paul Nash painting below, a fractured set of stumps piercing the sky.

Paul Nash – The Menin Road, 1919

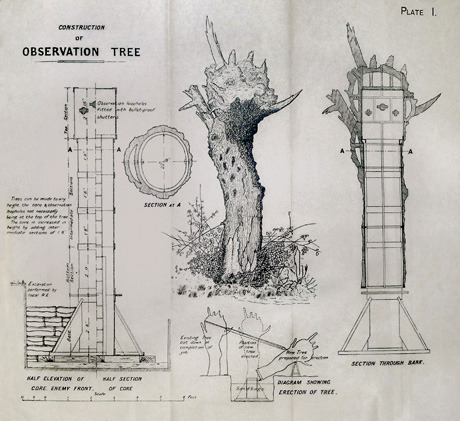

The plans for the Trees were drawn out in blue print to look like Shelled Trees and then would be transported to the place and erected side-wards and hope the enemy didn’t notice one new tree on the horizon

Construction blueprint plan of the Observation Tree.

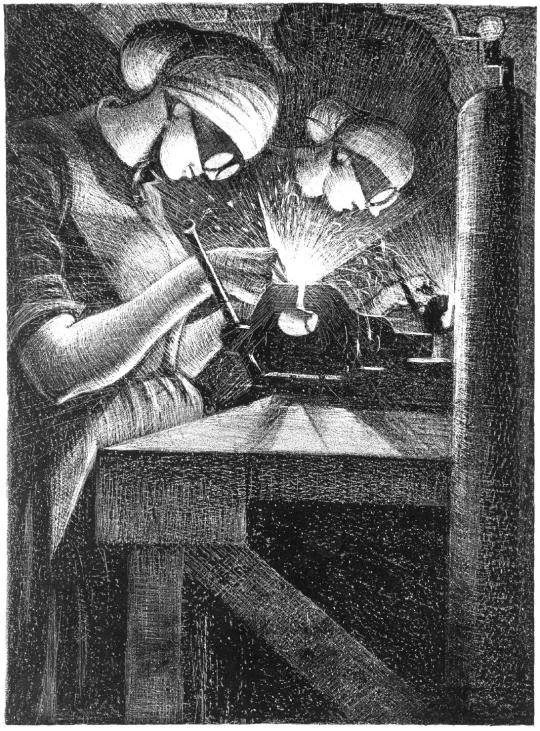

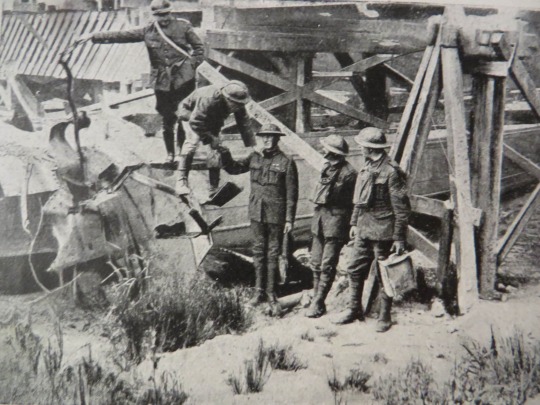

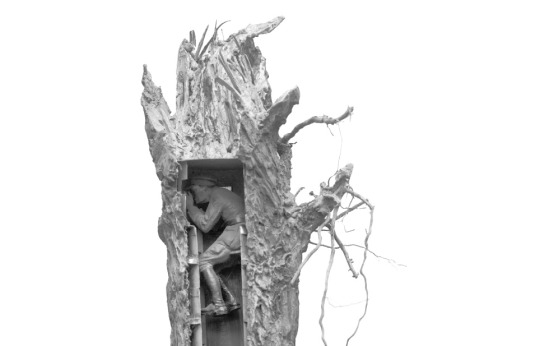

Below is a photograph of one of the trees in the state of manufacture. In front of the men are the shredded crowns of the trees.

Below is another photograph of a tree in situ on the field with a warren for the men to get in and out of. In the side would be a slit for the men to look out of, rather than looking over the top.

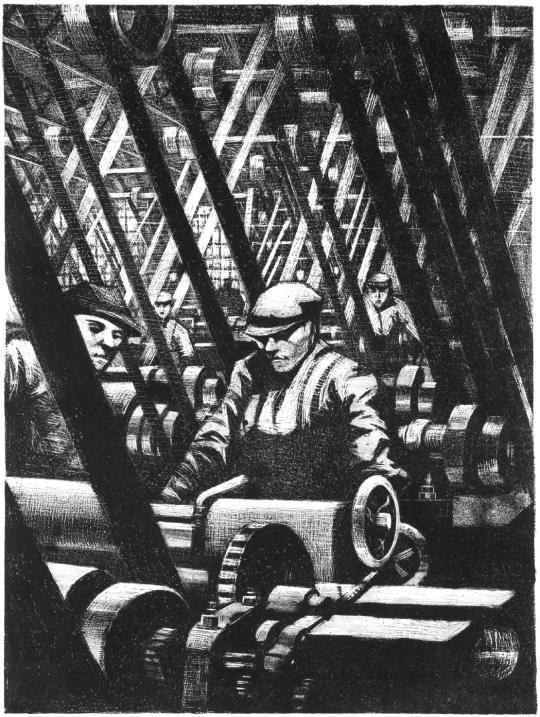

The painting below is a large Leon Underwood of how the tree was erected, foundations laid into the side of a trench so men could get under and in, others carrying the sides ready to be grafted together.

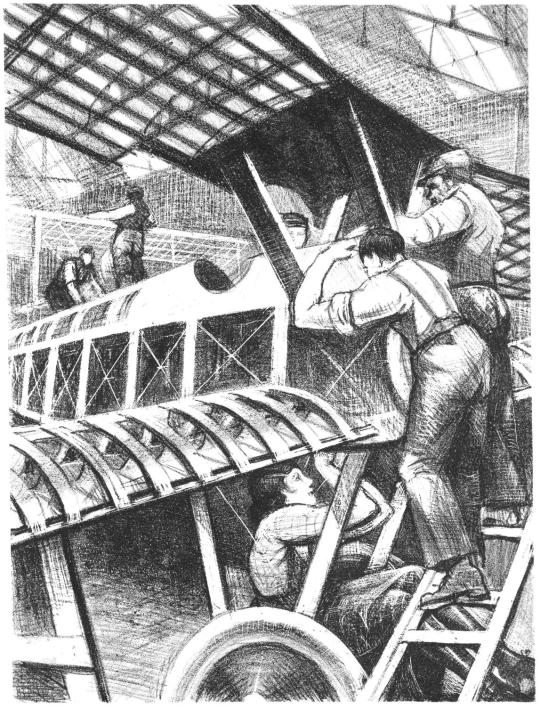

What I like about the camouflaged tree is how bonkers it is but also how obvious. Below is a painting in the epic, almost religious style by Leon Underwood, not unlike Jesus at the Cross.

Leon Underwood – Erecting a Camouflage Tree, 1919