It is always hard to say what the joy is in studio pottery, but I think it is knowing that it is crafted and made rather than mass produced in a factory. There has always been a tradition of decorated slipware in pottery as other than paintings, carvings in churches and textile embroidery there were few opportunities to ever see any decoration on items. If you did, it was normally because you too had money.

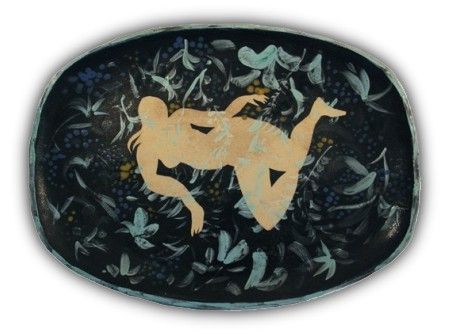

Thomas Toft – Staffordshire Slipware Dish, c1670-90

After the fashions of early slipware and large decorated chargers came the smaller refined pots that the public would buy in the Victorian periods. This followed the social change of home ownership and so factories had new markets to cater for. This is the time when Royal Doulton and Brannam Pottery both stopped making sewage pipes and chimney pots and started to make domestic kitchenware and vases.

Arthur Bamkin for Charles Brannam – Sgraffito Cup, 1898

After the fashions of early slipware and large decorated chargers came the smaller refined pots that the public would buy in the Victorian periods. This followed the social change of home ownership and so factories had new markets to cater for. This is the time when companies like Royal Doulton and Brannam Pottery both stopped making sewage pipes and chimney pots and started to make domestic kitchenware and vases.

Robert Wallace for Martin Brothers – Double Sided Face Jug, 1901

The Martin Brothers whose large birds command such high prices also demand a mention for they were the blurred line of Doulton’s factory made designs and Brannam Pottery’s craft. They created vases with bold and bright decoration before going into a series of ceramics with natural earthy tones. The most interesting thing about them is that they can be incredibly surreal, and, well, tacky. Some are beautiful, but I thought it was good to show some early surrealism.

Joseon Dynasty Moon Jar, 18c.

The moon Jar above is the most famous example of Bernard Leach’s effect on British Crafts. He bought the jar while out in the East and brought it back to Britain and when he died he left to Lucie Rie, who in-turn left it to the British Museum.

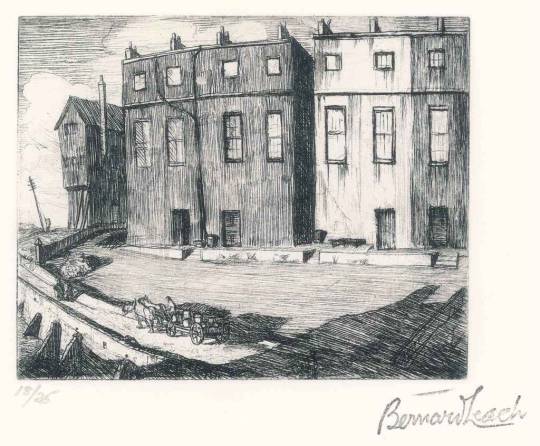

Bernard Leach was raised in the days of the British Empire. His father worked for the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank and as a child he was based in Hong Kong and in Japan before returning to Britain to attend schooling. He attended the Slade for a time and then the London School of Art in Kensington where he was taught etching by Frank Brangwyn. Leach was at this time very fond of Etching and returned to Japan with the intention of teaching it to the Japanese.

Bernard Leach – A London Scene (Etching), 1908-9. (Leach-Redgrave Restrike)

While in Japan Leach became obsessed by the craft of pottery and took lessons with Urano Shigekichi. After learning the industry for a year he set up his own pottery in Japan before moving to China. He exhibited his works and this lead to the introduction to Shōji Hamada.

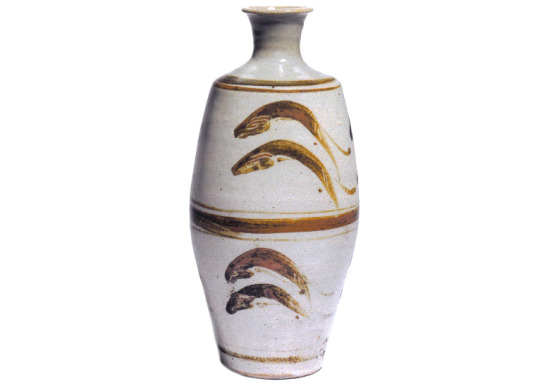

Bernard Leach – Leaping Fish Vase, c1965

Hamada was deeply impressed by a Tokyo exhibition of ceramic art by Bernard Leach, who was then staying with Yanagi Sōetsu, and wrote to Leach seeking an introduction. The two found much in common and became good friends, so much so that Hamada asked and was granted permission to accompany Leach to England in 1920 when the latter decided to return and establish a pottery there.

Edgar Skinner – a friend of Leach’s father introduced him to the St. Ives Guild of Handicrafts which was supported by local wealthy philanthropist called Francis Horne who lived at Tremorna in Carbis Bay. She offered him a capital loan of £2500 to set up his pottery with Hamada and also an assured income of £250 for 3 years.

The Leach Pottery was founded and over the next ten years they would experiment with the clays, slips and glazes in the UK and different woods to burn in the kilns. In 1923 Michael Cardew joined the pottery and left some years later to found Winchcombe Pottery.

The Leach Pottery took on various students to work there: Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie, Norah Braden, Charlotte Epton and Dorothy Kemp. It was not the only pottery but I think it is honest to say the Leach pottery and the skills learnt in Asia have made him important. His influence would go on when there was a serge in home pottery in the 1960s and people copied his designs and used his glaze recipes.

Charlotte Epton – Jar and Lid, c1930

The other pottery that helped the surge of British Studio Pottery would be at Dartington Hall. Bernard Leach helped set up the pottery in the late 1920s. He recommended Sylvia Fox-Strangeways who was the first potter at Dartington. She was joined by Marianne De Trey who would later run it and education pupils.

Many other potters were forging the way in Studio Pottery in the interwar years: William Staite Murray, Dora Billington, Lucie Rie, Ursula Mommens, Ray Finch and Hans Coper. But to list the styles they made, the shapes of pots and their individual glazes would make this post too long

In the 1960s and 70s in the UK there was a boom in the amount of small potteries. Some looked back at the methods of making pottery in the Leach-Asian tradition, some went on to make domestic wear, others just experimented with styles. There are so many wonderful potters from all over Britain and their decorations and ways of potting are all so different. To collect it now doesn’t have to be expensive as some galleries would have you believe and I have been both collecting and selling pots in Cambridge for years.

Peter C Arnold for Alderney Pottery – Pot and Lid, c1970

I don’t know if the modern potters would call it their moment of postmodernism, but there are many craftsmen out there who are experimenting with the size and form of things. Below is plate by Dylan Bowen who has an amazing eye for almost careless slip designs.

Dylan Bowen – Plate, c2015

Now some potters make record amounts at auction and museums have exhibitions of their pottery, like Kettle’s Yard with Jennifer Lee. In the 1990s David Bowie invested in the Leaping Fish Vase by Bernard Leach and in the sale of his collection of art it broke the record for a Leach work at £32,500.