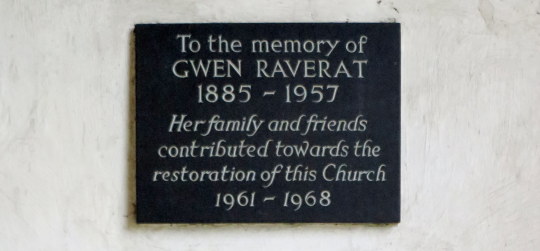

Within cycling distance from my home is the church at Harlton. The village is known now as the home of Gwen Raverat from 1925 to 1941, although she is buried with her family in Trumpington.

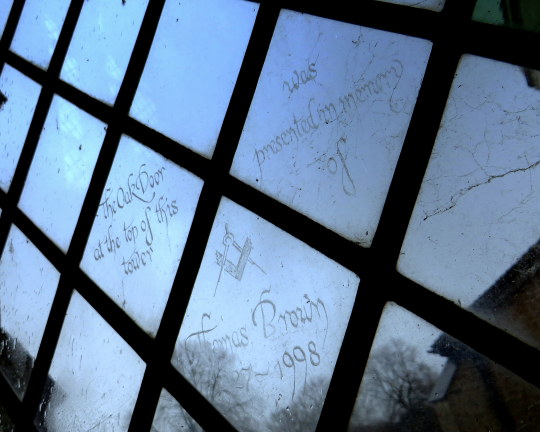

There are various monuments over the church, in windows and on plaques. Also over the church are bits of scratched graffiti as well as a large monument in alabaster and marble.

The Fryer Monument

The first John Fryer, father of Thomas Fryer, the elder of the men commemorated on the monument, was born at Balsham and educated at Eton, King’s College Cambridge, and the University of Padua, then the greatest medical school in Europe. Although he was for a time a Lutheran, and was indeed imprisoned for heresy in the 1520s, by 1561 he was imprisoned in the Tower of London for Catholicism. He was released in 1563, but died of the plague in October of that year.

A scratched Elizabethan gravedigger with spade.

Said to be a consecration mark this pattern can be found all over the country, in churches, barns, castles and on furniture. Most people call them Daisy Wheels or Hexfoils.

The root screen below is said to be Cambridgeshire’s only one made totally of stone.

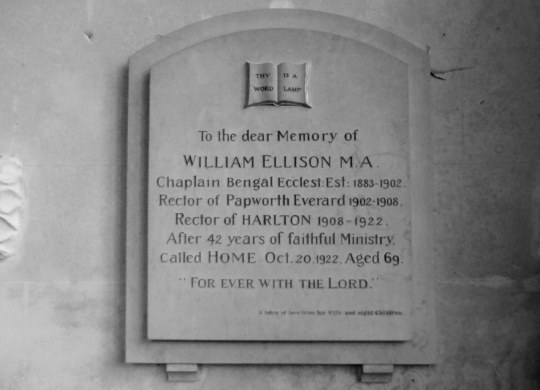

The rector of the church in 1908-1922 was William Ellison and his son, Jan was the carver of the twelve disciples in the reredos – in the style of Eric Gill. One of eight children, Henry Jan was born in Harlton, and studied sculpture in Paris with Ossip Zadkine. There he met many of the key figures of the artistic avant-gardes of the 1920s and ’30s. In 1935 he designed sculpture for Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry’s Sun House in Hampstead.

After working as an intelligence agent in the Middle East during World War Two, he re-trained in ceramic studies at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, London. He set up the Cross Keys Pottery in Cambridge with his wife Zoë. The church now has three of their vases inside and two wall planters.