To my bias opinion, Faber & Faber have always seamed a more artistic publisher based on the work in the 1930’s and 40’s. The typesetting of the poetry to the beautifully illustrated dust jackets always seam to be ahead of other publishers when it came to literature and how to employ artists.

The Ariel poems were a series of 38 pamphlets that contained illustrated poems published by Faber and Gwyer and later by Faber and Faber.

Faber and Faber began as a firm in 1929. However, its roots go back further — to The Scientific Press, owned by Sir Maurice and Lady Gwyer and derived much of its income from the weekly magazine the ‘Nursing Mirror’.

The Gwyers aimed for trade publishing and this led them to Geoffrey Faber. The partnership was then founded in 1925 and known as Faber and Gwyer. It was at this time In 1925 that T.S.Eliot left Lloyds bank to join the publishing firm Faber and Gwyer, as an editor.

The partnership of Gwyers and Faber didn’t last for long, four years later in 1929, the Nursing Mirror was sold and Geoffrey Faber and the Gwyers parted company. Searching for a name with a ring of respectability, Geoffrey hit on the name Faber and Faber, although there was only ever one Faber.

In 1927, Eliot was asked by Geoffrey Faber, to write one poem each year for a series of illustrated pamphlets with holiday themes to be sent to the firms clients and business acquaintances as Christmas greetings.

This series became the “Ariel Series” and would amass 38 pamphlets from a selection of English writers and poets from 1927 through 1931. It was a mark of considerable taste by Faber & Faber as they paired their authors with modern artists.

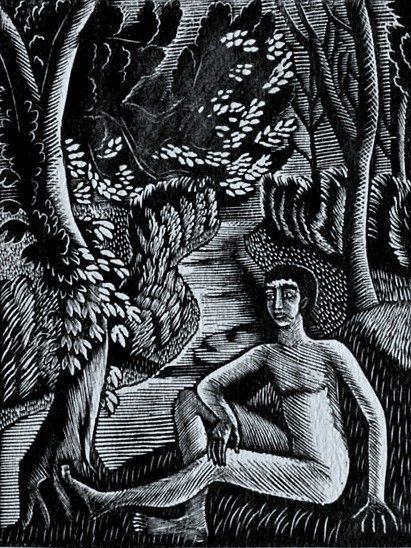

A detail of the wood engraving by Gertrude Hermes for Ariel Poem #23

The first editions of the Ariel Poems where released in numbers of 3000–5000 printings per copy. A set of limited editions where also issued in various printings of 250–500 copies each. These were signed and numbered by the authors and bound with thicker hand cut paper. Both versions of the editions had an illustration on the front cover, then a frontispiece by the illustrator that was sometimes coloured. Then the poems text. The pamphlets were bought back in 1954, when eight new publications were released in the New Series. These came with a colourful envelope from when they were posted.

The pamphlets, in order, are as follows:

- Yuletide in a Younger World by Thomas Hardy, drawings by Albert Rutherston

- The Linnet’s Nest by Henry Newbolt, drawings by Ralph Keene

- The Wonder Night by Laurence Binyon, drawings by Barnett Freedman

- Alone by Walter de la Mare, wood engravings by Blair Hughes-Stanton

- Gloria in Profundis by G. K. Chesterton, wood engravings by Eric Gill

- The Early Whistler by Wilfred Gibson, drawings by John Nash

- Nativity by Siegfried Sassoon, designs by Paul Nash

- Journey of the Magi by T. S. Eliot, drawings by E. McKnight Kauffer

- The Chanty of the Nona, poem and drawings by Hilaire Belloc

- Moss and Feather by W. H. Davies, illustrated by Sir William Nicholson

- Self to Self by Walter de la Mare, wood engravings by Blaire Hughes-Stanton

- Troy by Humbert Wolfe, drawings by Charles Ricketts

- The Winter Solstice by Harold Monro, drawings by David Jones

- To My Mother by Siegfried Sassoon, drawings by Stephen Tennant

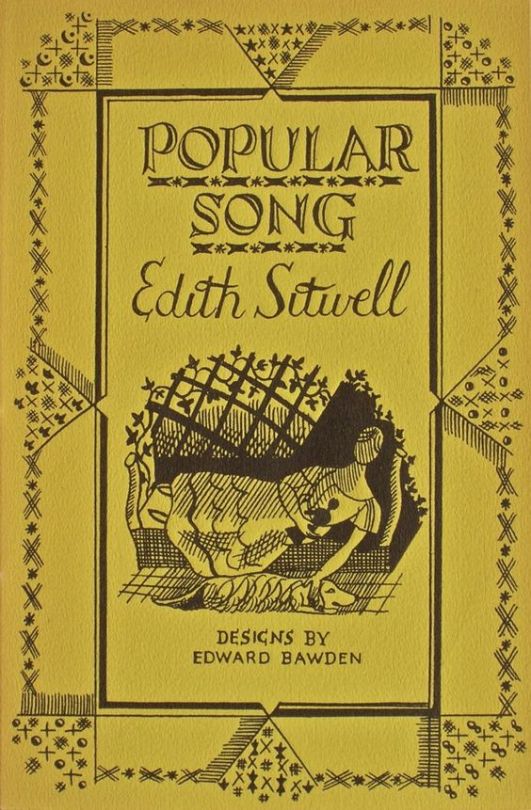

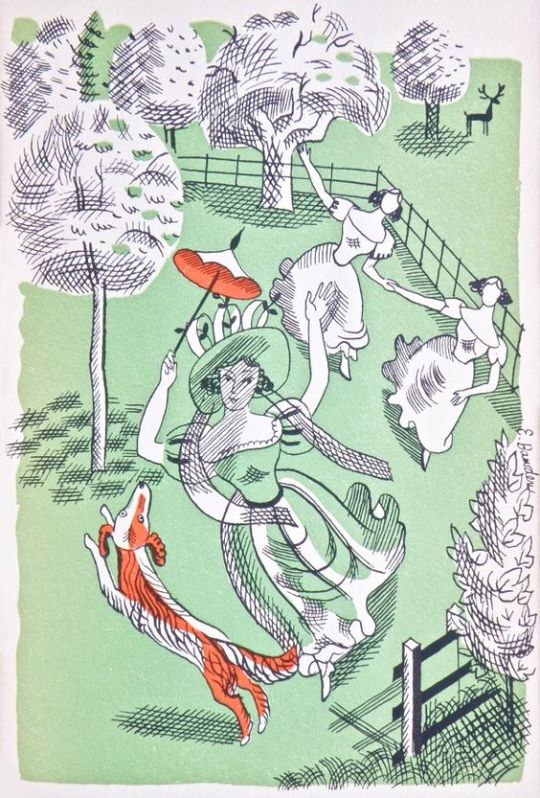

- Popular Song by Edith Sitwell, designs by Edward Bawden

- A Song for Simeon by T. S. Eliot, drawings by E. McKnight Kauffer

- Winter Nights, a reminiscence by Edmund Blunden, drawings by Albert Rutherston

- Three Things by W. B. Yeats, drawings by Gilbert Spencer

- Dark Weeping by “AE”, designs by Paul Nash

- A Snowdrop by Walter de la Mare, drawings by Claudia Guercio

- Ubi Ecclesia by G. K. Chesterton, drawings by Diana Murphy

- The Outcast by James Stephens, drawings by Althea Willoughby

- Animula by T. S. Eliot, wood engravings by Gertrude Hermes

- Inscription on a Fountain-Head by Peter Quennell, drawings by Albert Rutherston

- The Grave of Arthur by G. K. Chesterton, drawings by Celia Fiennes

- Elm Angel by Harold Monro, wood engravings by Eric Ravilious

- In Sicily by Siegfried Sassoon, drawings by Stephen Tennant

- The Triumph of the Machine by D. H. Lawrence, drawings by Althea Willoughby

- Marina by T. S. Eliot, drawings by E. McKnight Kauffer

- The Gum Trees by Roy Campbell, drawings by David Jones

- News by Walter de la Mare, drawings by Barnett Freedman

- A Child is Born by Henry Newbolt, drawings by Althea Willoughby

- To Lucy by Walter de la Mare, drawings by Albert Rutherston

- To the Red Rose by Siegfried Sassoon, drawings by Stephen Tennant

- Triumphal March by T. S. Eliot, drawings by E. McKnight Kauffer

- Jane Barston 1719–1746 by Edith Sitwell, drawings by R. A. Davies

- Invitation To Cast Out Care by Vita Sackville-West, drawings by Graham Sutherland

- Choosing A Mast by Roy Campbell, drawings by Barnett Freedman

The 1954 series was as follows:

- Sirmione Peninsula by Stephen Spender, drawings by Lynton Lamb

- The Winnowing Dream by Walter de la Mare, drawings by Robin Jacques.

- The Other Wing by Louis Macneice, drawings by Michael Ayrton.

- Mountains by W. H. Auden, drawings by Edward Bawden.

- Nativity by Roy Campbell, drawings by James Sellars.

- Christmas Eve by C Day Lewis, drawings by Edward Ardizzone

- The Cultivation of Christmas Trees by T. S. Eliot, drawings by David Jones.

- Prometheus by Edwin Muir, drawings by John Piper.