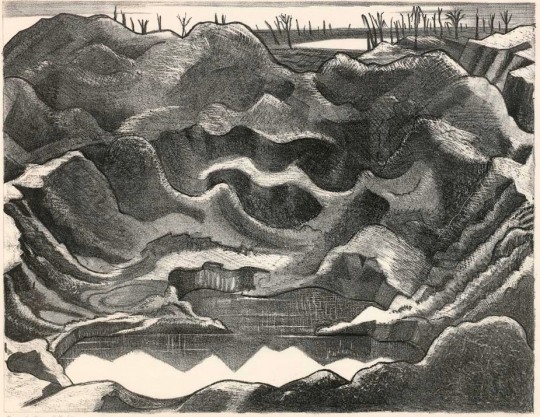

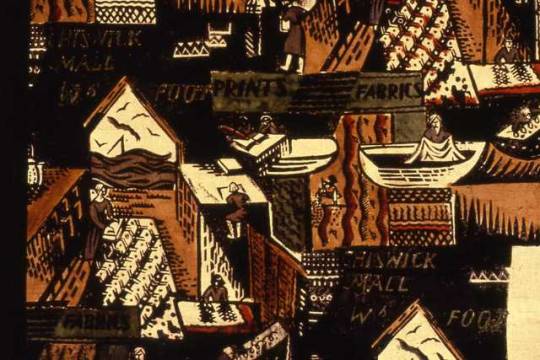

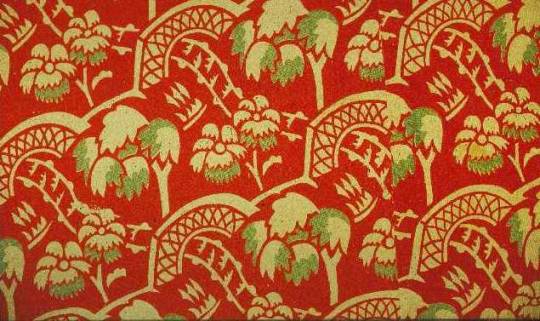

Joyce Clissold – ‘Footprints’ c.1928 for Footprints Ltd.

The Footprints workshop started life as a printing press for dress and furnishing fabrics using traditional hand-block printing. It was set up in 1925 by Gwen Pike and Elspeth Little in Durham Wharf, Hammersmith and supported by Celandine Kennington (the wealthy second wife of the artist Eric Kennington). The name, Footprints, was chosen because of the foot pressure used to create most of the block prints.

Originally the Pike and Little partnership was one of artist and business; Elspeth Little owning a shop called ‘Modern Textiles’ and Gwen Pike being the artist / designer of ‘Footprints’.

Modern Textiles was opened in 1926 by Elspeth Anne Little, who had studied painting at the Central and Slade Schools. She had become involved with textiles and block printing by being employed in a theatrical workshop after leaving college.♠

Elspeth Little was taken on in 1923 as an apprentice at ‘Fraser, Trelevan and Wilkinson’ – the theatrical workshop run by Grace Lovat Fraser, widow of the designer Claude Lovat Fraser. The pressure of work meant that Elspeth Little soon became an employee, not a trainee, and as such she was involved in printing fabrics for theatre sets and costumes.

Encouraged by Paul Nash, she opened a shop to sell a variety of craft made goods. It was the intention of Modern Textiles to promote superior design and production as an alternative to what were seen as the “hackneyed and exhausted” offerings being mass-produced repetitively by many English manufacturers. This was emphasised in the shop’s publicity which stated that:

“The object of “Modern Textiles” is to sell work of good design, principally fabrics of various kinds. A few people already know that well designed materials are being made by one or two artists, but the promoters of “Modern Textiles” believe a very much larger public than is generally supposed would be eager to buy stuffs of individuality and beauty, whether for dresses or furnishing, if there were better opportunity for selection”. ♠

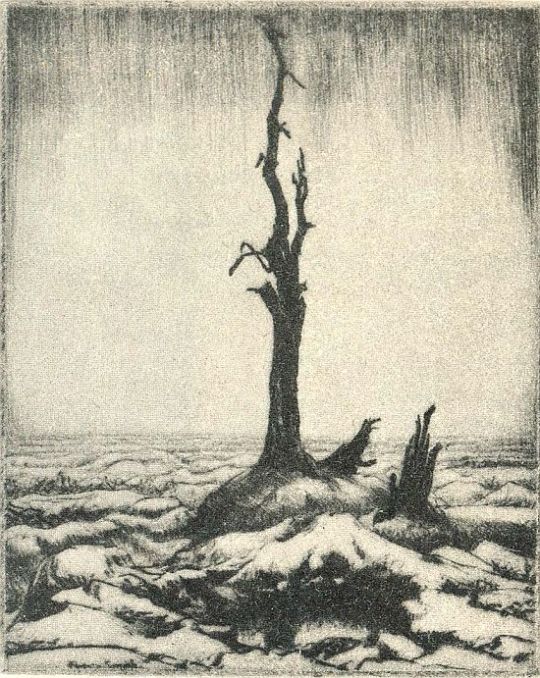

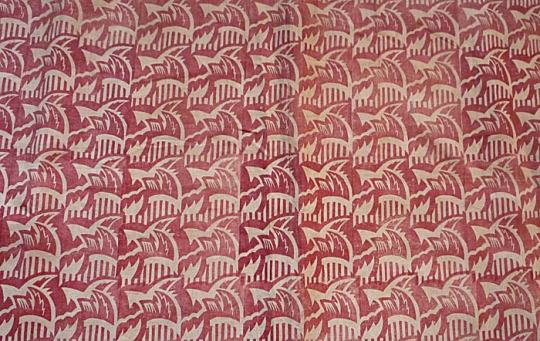

Joyce Clissold – fabric print for Footprints Ltd. c1930s

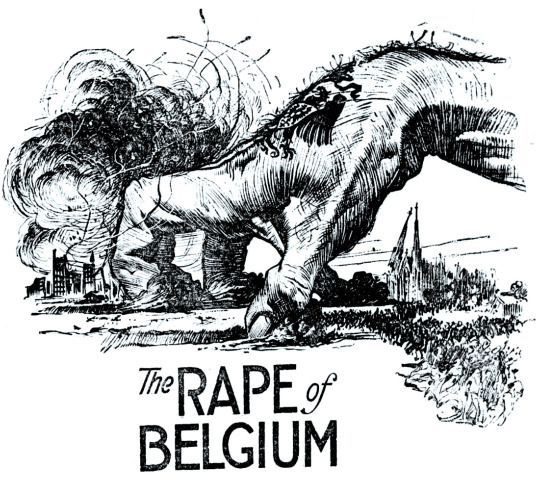

Elspeth Little sold lengths of fabric, scarves, shawls, cloaks, dressing gowns, velvet jackets and other small ready to wear items, plus some ceramics. Block printed linens and velvets by Phyllis Barron and Enid Marx and batiks by Marion Dorn were offered along side painted and printed fabrics by Miss Little, and artists Paul Nash, Eric Kennington and Norman Wilkinson.Miss Little had a workroom behind the shop where she printed her own textile designs from lino blocks. However, the majority of printing for Modern Textiles was carried out by Footprints, a workshop established to supply the shop. ♠

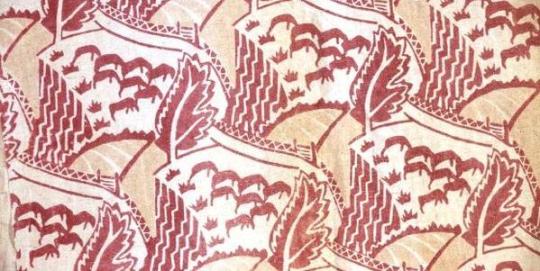

Doris Gregg – ‘Welwyn Garden City’, 1930. Lino block print. Footprints Ltd.

The Footprints workshop became the longest-lasting block printing enterprise of the 1920s and continued (despite the break up of the Pike-Little partnership) until after the war. It was predominantly a female workforce. Workers would enter the studio as an apprentice, working making dyes and assisting with printing before designing their own work, this made sure that all the staff were competent in the main processes of the studio.

Doris Scull – ‘Sheep’ for Footprints Ltd.

The most recent group of designers and engravers on linoleum for producing textile patterns is that established by the energy and resource of Mrs. Eric Kennington (nee Edith Celandine Cecil), in a workshop by the river at Hammersmith. The chief craftswoman here is Mrs. Gwen Pike, a most experienced and able engraver and printer. The works, known as Footprints, reproduce patterns by their own staff, and also designs contributed by independent artists. ‡

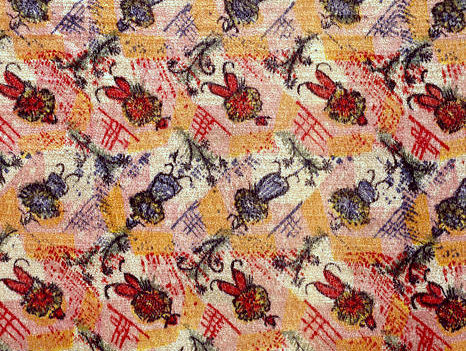

Joyce Clissold – Fabric designed for Footprints Ltd with the original lino block below.

Joyce Clissold arrived in two years into Footprints life in 1927, and continued Footprints when Pike and Little split in 1929. Clissold studied at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, learning wood engraving and lino cutting in the printing rooms. When she started working at Footprints she was a student and it was a small printing workshop on the Thames outside London, she is mostly to credit for turning it into a viable business. She focused most on the creative input of designing and block cutting but helped Footprints establish their own set of shops independent of ‘Modern Textiles’ after 1929.

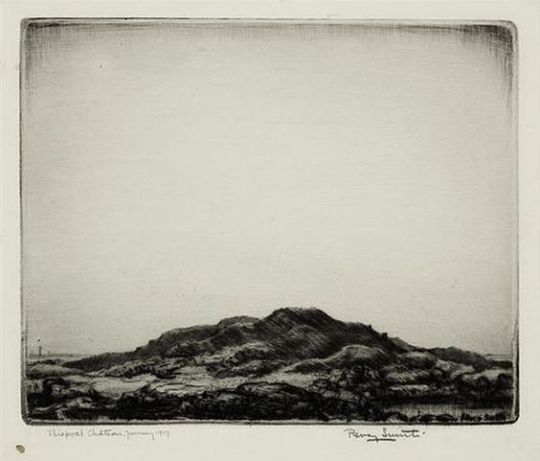

Footprints Studio, Brentford, 1934-35

In the mid-1930s she relocated Footprints to enable her to live and work on the same premises. The new situation reflected the tradition of textile production by women at home. Household and workshop activities intermingled. The kitchen became known at the “lab”. But the domestic setting belied the fact of an effective business. In its heyday there were 40-50 employees involved in the production, making up, distribution and sale of printing fabrics. The first Footprints shop opened in New Bond Street, London, in 1933 to sell dress and furnishing fabrics; it moved to a more stylish location in 1936, near, near to furriers, milliners and gown markers. An additional shop was established in 1935 in fashionable Knightsbridge. Footprints’ textiles provided interesting alternatives to predictable modernist trends and appealed to artistic customers such as Gracie Fields and Yvonne Arnaud. †

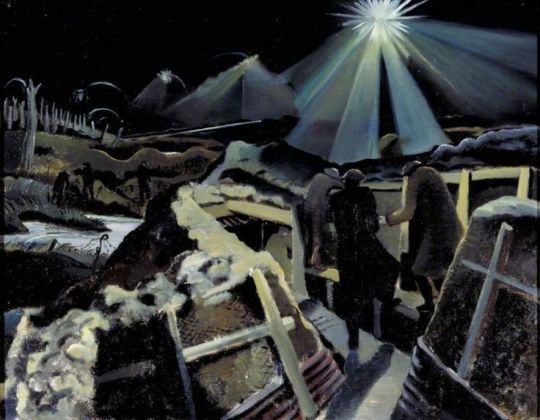

Paul Nash fabric design. Printined by Footprints Ltd.

The Footprints shops and represented artists like Paul Nash, Eric Kennington and Marion Dorn. Footprints used a much wider colour range than Barron and Larcher. Block printed fabric was very much the desire of the Avant-garde and influential. Without machines the fabrics were hand printed, this was a slow process. These fabrics were exclusive and expensive with the average price of hand printed fabrics, at 12 shillings per yard, while manufacturers such as Warners could produce printed textiles for 6 shillings per yard.

In 1940 Clissold had to close the shops due to the lack of essential supplies and the female employees being required for war work. The workshop managed to re-open after the war, but with fewer printers and a more modest range. †

Paul Nash – Two variations on ‘Big Abstract’ printed by Footprints Ltd.

Other clients included Deitmar Blow, the architect to the Duke of Westminster, and the stylish and fashionable decorator Syrie Maugham.

† Dictionary of Women Artists by Delia Gaze, 1997. 9781884964213

Modern Block Printed Textiles by Alan Powers, 1992. 9780744518917

‡ The Woodcut No.1 An Annual, 1927.

♠ Printed Textiles: Artist Craftswomen by Hazel Clark, 1989