During the Second World War in 1941, Cambridge was hit by many bombing raids. One of the most deadly was on the 24th of February when ten people lost their lives on Hills Road between the Catholic Church and the Station.

The main blast appears to have been outside The Globe Inn and Bull’s Dairy. This evening at the station in Cambridge an important consignment of tanks was being unloaded. That has given the rumours ever since that the Germans had intelligence, possibly from the Dutch agent Jan Ter Braak who was known to have been operating in Cambridge at the time.

At 11pm a 50kg high explosive bomb exploded on the roof of the Catholic church’s sacristy; it blew a six foot hole in the roof and a similar sized hole in the wall of the Sacred Heart Chapel.

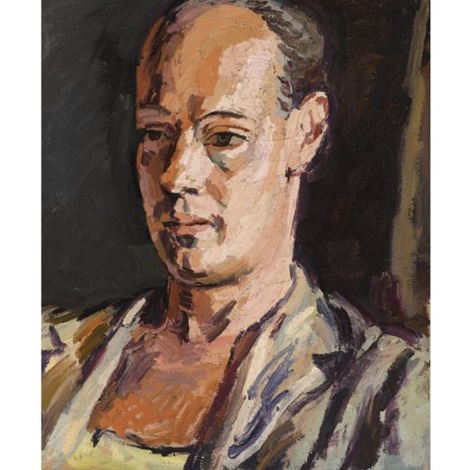

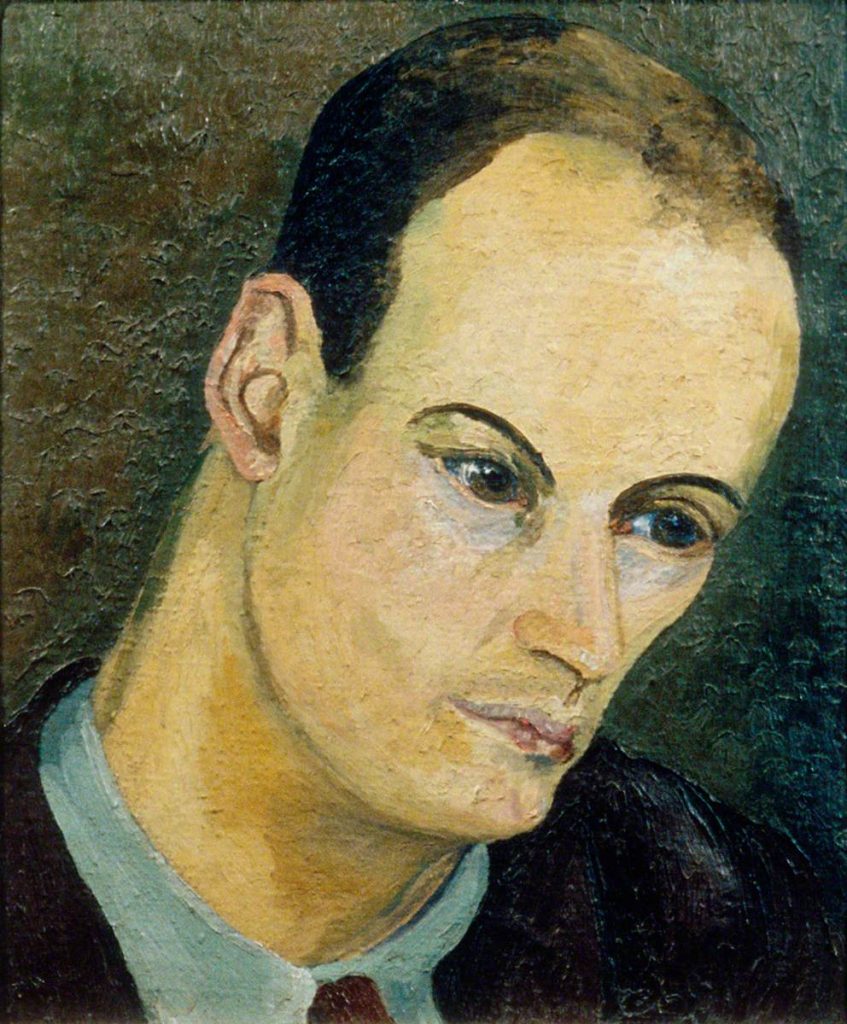

Petica Coursolles Robertson

Civilian. Died 24th February 1941. Aged 57. Air Raid Warden; W.V.S. Daughter of the late Major and Mrs. Charles Jones; wife of Professor D. S. Robertson, of 56 Bateman Street. Died at Russell Street. Buried in CAMBRIDGE, MUNICIPAL BOROUGH CEMETERY, Cambridge.

Petice was born to of Major Charles Jones of the Royal Artillery and Mary Jane Ross in London. Her sister became famous as the writer and editor Emily Beatrix Coursolles (“Topsy”) Jones, they were both educated at Saint Felix School, Reydon, Southwold.

Jones’s first novel, Quiet Interior, was published in 1920 and praised by such notable contemporary authors as Katherine Mansfield and Rebecca West. She went on to write a handful of other novels: The Singing Captives (1921), The Wedgwood Medallion (1923), Inigo Sandys (1924), Helen and Felicia (1927), and Morning and Cloud (1932).

Petica married Martin Robertson. They had two children; Charles and Giles. After Petica died Martin married a family friend, Cecil (née Spring Rice) whom he had known as a family friend; and they had another child, Lucy. While her husband was posted overseas to North Africa, Cecil took her family to Iken, Suffolk, not far from Aldeburgh, where her own

mother, Margie, was running a nursery school for evacuees.

In 1984 as a result of an accident in the garden of their Parker Street house Cecil fell to her death.

Kathleen [Ada Irene] Thaxter

Civilian. Died 24th February 1941. Aged 24. Fire Watcher; of 147 Sturton Street. Daughter of Charles Thaxter, of 17 Merton Street, Newnham. Died at Hills Road. Buried in CAMBRIDGE, MUNICIPAL BOROUGH CEMETERY, Cambridge.

Ivy [Florence] Woodcock

Civilian. Died 24th February 1941. Aged 29. of Hills Road. Daughter of the late Mr. and Mrs. Jessup, of 47 Argyle Street; wife of Percy Cyril Woodcock. Died at Hills Road. Buried in CAMBRIDGE, MUNICIPAL BOROUGH CEMETERY, Cambridge.

Bertie Thomas Ashman

Civilian. Died 24th February 1941. Aged 42. St. John’s Ambulance Brigade; of 48 Hills Road. Son of J. L. and M. Ashman, of 46 Sedgwick Street; husband of Rene Ashman. Died at 48 Hills Road. Buried in CAMBRIDGE, MUNICIPAL BOROUGH CEMETERY, Cambridge.

Sidney Harold Brittain

Civilian, Died 25th February 1941. Aged 50. Husband of Phyllis Edith Kate Brittain, of 80 Castle Street. Injured 24 February 1941, at Hills Road; died at Addenbrookes Hospital. Buried in CAMBRIDGE, MUNICIPAL BOROUGH CEMETERY, Cambridge.

William Brittain born about 1869 to Charles and Besty Brittain he was married to Susan Jane Bell 1892

Sidney Brittain age 50 of 80 Castle Street Cambridge, died outside The Globe Pub in Hills Rd, on the night of Mon 24th Feb, in a Bombing raid aimed at Troop and munitions movements at the near by marshalling yard. It was believed to have been coordinated by a Dutch Nazi spy who killed himself when he realised Police were on to him

[William] John Frederick Day

Sapper 1927204, 150 Railway Construction Company, Royal Engineers. Died 24th febraury 1941. Aged 29. Son of William and Mabel Day, of Cambridge; husband of Doris May Day, of Marylebone, London. Buried in CAMBRIDGE CITY CEMETERY, Cambridge. Grave 6042.

Lucy Sybil Gent

Civilian. Died 24th February 1941. Aged 60. Air Raid Warden W.V.S.; of 76 Hills Road. Died at Hills Road. Buried in CAMBRIDGE, MUNICIPAL BOROUGH CEMETERY, Cambridge.

Maurice Herbert George Lambert

Civilian. Died 2nd March 1941. Aged 34. of 25 Hills Road. Son of A. G. and C. E. Lambert, of 68 Hills Road; husband of Ivy Lambert. Injured 24 February 1941, at Hills Road; died at Addenbrookes Hospital. Buried in CAMBRIDGE, MUNICIPAL BOROUGH CEMETERY, Cambridge.

Frederick [Dennis Charles] Negus

Civilian. Died 25th February 1941. Aged 19. Home Guard; of 87 Russell Street. Son of Frederick John and Ellen Elizabeth Negus, of London. Injured 24 February 1941, at Hills Road; died at Addenbrookes Hospital. Buried in CAMBRIDGE, MUNICIPAL BOROUGH CEMETERY, Cambridge.