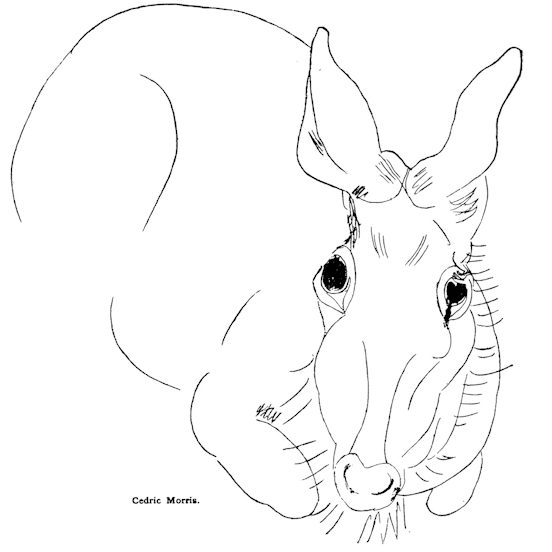

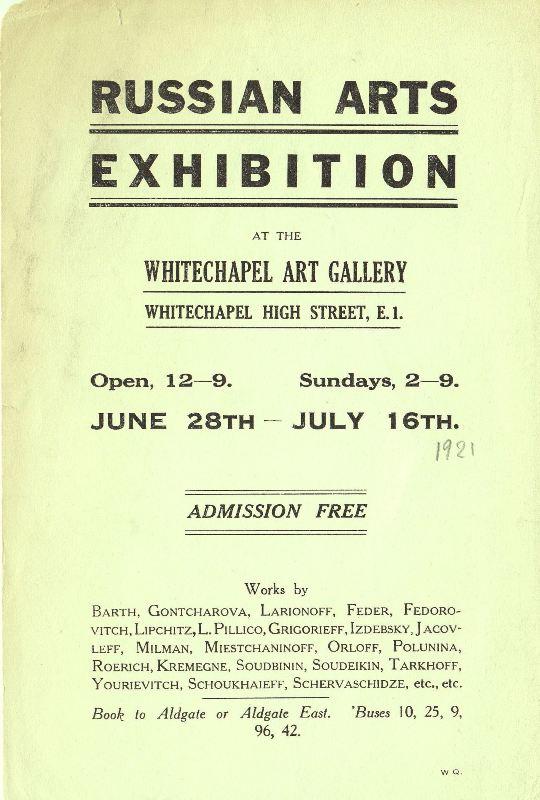

In my shopping habits, I end up with lots of odd periodicals. This one from The Egoist Press’s magazine The Tyro (1922) has a curious set of editorial quirks – An essay on Russian Artists by Dismorr and an illustration by a young Cedric Morris. It sadly is a home for more of Wyndham Lewis’s ravings on art. The show was likely the 1921 Exhibition of Russian Arts and Crafts at the Whitechapel Galleries. It featured work by artists fleeing the revolution and living in London and Paris. Cagall, Goncharova, Larionov, Vasil’eva, Jacques Lipchitz and Arkhipenko and Pilichowski.

Some Russian Artists by Jessica Dismorr

THE show of exiled Russians at Whitechapel was noteworthy not for the artistic achievements, but as an expression of national character in art..

No other country of Europe has such marked æsthetic predilections. A bias towards clearness of presentment, emphatic shapes and strong colour is hers by inheritance. Naiveté, a farce in Paris and London, is true here. Toys and eikons give with homely terseness the character of the race.

The work of Goncharova is a good example of the toy-making gift. Inventiveness sprung directly from tradition reached in her setting to the “Coq d’or” its finest flower. At Whitechapel she exhibits cubist devices grafted on to immemorial patternings of peasant costume. Her juxtaposed chromes and majentas, so “moderniste” and daring, are commonplaces of the primitive steppe village.

Sarionoff plays a more involved game, dovetailing bright splinters of colour into the forms of men and objects. By his method much animation is suggested in the artificial stage atmosphere for which he works. Vassilieva paints dexterously a world in which all surfaces are fresh paint, all people dolls, all manners the story-book code.

Chagal, wandering Jew, mentally native to Russia is the curious vessel of the national spirit. His subject matter is legend and fairy- tale, his personal adventures or the bald drama of peasant life. Not an illustrator, he is a summoner of forms, all of which have story as well as shape. Men, small and large, numerous important animals, fantastic suns and moons, carts and churches jostle one another throughout these amazing designs. Here, though natural congruities are outraged, there is a plastic orderliness preserved as by a miracle.

Two sculptors of talent seek emancipation of a different kind.

Archipenko has been known in Paris exhibitions for block-like stone pieces, so sparingly treated by the chisel as to leave all their natural weight and inertia. A change of intention is seen in his newest works which possess on the contrary great formal variety. Freeing his subject from all but certain selected aspects he traces in air the whorls and spirals of a sculptural shorthand.

With Lipschitz we find a fiercer disdain of realism. The sources of human form disappear as his scheme develops, and a new thing is produced relying upon itself for significance. He works to discover an ideal organisation, one plane pre-supposing another till the sum of parts is reached. Such an endeavour is a searching test of natural gift, for in those polar regions of conquest it has no allies. When Lipschitz fails it is due to an enterprise supported by a talent not equally mature.

Jessie Dismorr.