I love discovering interesting artists, the research and uncovering details of their life and then buying works to sell, but before the lock down, little did I know that I would buy a painting stolen from the Victoria and Albert Museum. I want to give it back to them but their staff are all furloughed until August.

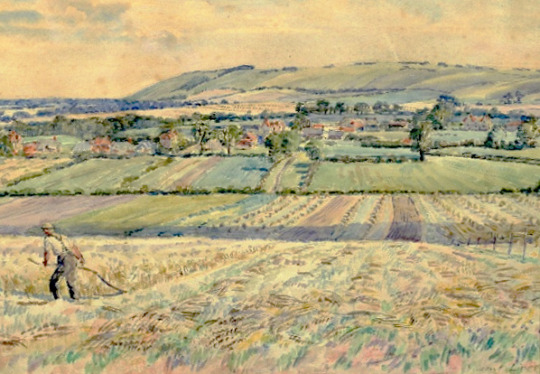

The painting was a watercolour by Vincent Lines, an artist with an interesting past. Lines education started at the London Central School of Arts and Crafts, then in 1931 he was admitted into the Royal College of Art. He was influenced by A.S.Hartrick and Thomas Hennell. He worked as a watercolour artist and an illustrator. He became Principal of Horsham art school in 1935. He was one of the artists chosen to work on the Recording Britain project, and that is one of the things that attracted me to him.

During the Great Depression in America artists were employed by the state to make works for the public. It was called the Federal Art Project and from 1935 the project was mostly famous for many murals in post offices and public buildings across America, but it also covered sculpture and graphic design work. The project is said to have made 200,000 works from 1935 to 1943.

The director of the National Gallery, Sir Kenneth Clark was inspired by the Federal Art Project in the run-up to the Second World War. In 1940 the Committee for the Employment of Artists in Wartime (part of the British Ministry of Labour and National Service) launched a scheme to employ artists to record the home front, funded by a grant from the Pilgrim Trust. It ran until 1943 and some of the country’s finest watercolour painters, such as John Piper, Rosemary Ellis, Rowland Hilder, and Barbara Jones were commissioned to make paintings and drawings of places which captured a sense of national identity. Their subjects were typically English: market towns, villages, churches, country estates, rural landscapes; industries, rivers, monuments and ruins. They were documenting characteristic scenes in a way never undertaken before.

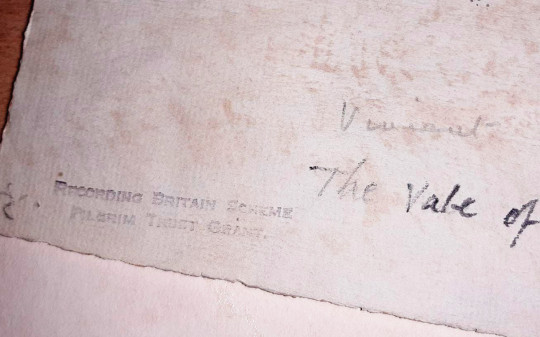

So how did I discover my purchase was stolen? I bought the painting at auction over the internet and had it posted to me, when it arrived the glass was broken, so I took it apart. Unusually it had no tape on the back and it was in a cheap clip frame giving easy access to the back; I thought this was odd as the auction house could see it was titled but they had called it “landscape with farm worker” and I assumed when buying it, that was the title. On the back of the painting it had the full details, Vincent Lines, and the name “Vale of Shalbourne”. Did they Google the real title “Vale of Shalbourne” and found the same listing on the V&A website? Who knows but it feels unusual for an auction house not to research a painting they are consigning.

Further-more, I had taken the back off the picture and at first I found a stamp for Recording Britain, then the allocation number. The code when typed into the V&A website comes up with a listing for “The Vale of Shalbourne” by Vincent Lines, is is listed as “In Storage”. Being listed with the code it couldn’t have been a rejected work by Lines for the project. The Recording Britain board chose what they bought, leaving more prolific artists some works to sell, but these were not stamped. Though the Pilgrim Trust funded the scheme they gave all the works, over 1500, to the Victoria and Albert Museum to document and keep. Due to the large number of works created, many works were given to regional collections and it is likely this painting was either stolen or wrongly disposed off by one of these regional collections or a council disposing of work. From the frame the watercolour came in, the style of mount and the amount of dirt on the glass I would guess this was framed in the early 1990s. When it was stolen I couldn’t guess, nor why.

I have emailed the V&A but had nothing back due to Covid Lockdown, but I will wait and see what they say. It would be curious to know if it was loaned out to regional collection or if it was stolen from London. The plot thickens. It is my intention to return it to them. Though technically I lost money from this there is a satisfaction of having done the right thing and returning a work to it’s home. Other collectors of Vincent Line’s work were the King, the Government Art Collection, Hertfordshire Pictures for Schools and the Royal Library. Thankfully I legitimately own the Hertfordshire Pictures for Schools painting as they were all sold off when the council wanted to make some money, but that is another story.

—————————-

I love discovering interesting artists, the research and uncovering details of their life and then buying works to sell, little did I know that I would buy a painting stolen from the Victoria and Albert Museum. I gave it back, losing in money but gaining in spirit.

It was by Vincent Lines, an artist with an interesting past. Lines education started at the London Central School of Arts and Crafts, then in 1931 he was admitted into the Royal College of Art. He was influenced by A.S.Hartrick and Thomas Hennell.He worked as a watercolour artist and an illustrator. He became Principal of Horsham art school in 1935. He was one of the artists chosen to work on the Recording Britain project and that is one of the things that attracted me to him.

During the Great depression in America artists were employed by the state to make works for the public. It was called the Federal Art Project and from 1935 the project was mostly famous for the murals in post offices, but it also covered sculpture and graphic design work. The project is said to have made 200,000 works from 1935 to 1943.

The director of the National Gallery, Sir Kenneth Clark was inspired by the Federal Art Project in the run-up to the Second World War years. In 1940 the Committee for the Employment of Artists in Wartime, part of the British Ministry of Labour and National Service, launched a scheme to employ artists to record the home front, funded by a grant from the Pilgrim Trust. It ran until 1943 and some of the country’s finest watercolour painters, such as John Piper, Sir William Russell Flint, Rowland Hilder, and Barbara Jones were commissioned to make paintings and drawings of places which captured a sense of national identity.

Their subjects were typically English: market towns, villages, churches, country estates, rural landscapes; industries, rivers, monuments and ruins. They were documenting characteristic scenes in a way never undertaken before.

How did I discover it was stolen? I bought the painting at auction and had it posted to me, when it arrived the glass was broken so I took it apart. Unusually it had no tape on the back and it was in a cheap clip frame giving easy access to the back; I thought this was odd as the auction house could see it was titled but they had called it “landscape with farm worker” and I assumed when buying it, that was the title. Did they google the real title “The Vale of Shalbourne” and found the same listing on the V&A website? Who knows but it feels unusual.

So I had taken the back off the picture and at first I found a stamp, then the allocation number. Stamp Above, Number below. The code when typed into the V&A website comes up with a listing for “The Vale of Shalbourne” by Vincent Lines, is is listed as “In Storage”.

Being listed with the code it couldn’t have been a rejected work. The Recording Britain board chose what they bought, leaving more prolific artists some works to sell, but these were not stamped. Though the Pilgrim Trust funded the scheme they gave all the works, over 1500, to the Victoria and Albert Museum to document and keep. Due to the large number of works created, many works were given to regional collections and it is likely this painting was either stolen or wrongly disposed off by one of these regional collections or a council disposing of work.

From the frame the watercolour came in, the style of mount and the amount of dirt on the glass I would guess this was framed in the early 1990s. When it was stolen I couldn’t guess, nor why.

I called the V&A and …

Though technically I lost money from this there is a satisfaction of having done the right thing and returning a work to it’s home. Other collectors of Vincent Line’s work were the King, the Government Art Collection, Hertfordshire Pictures for Schools and the Royal Library.