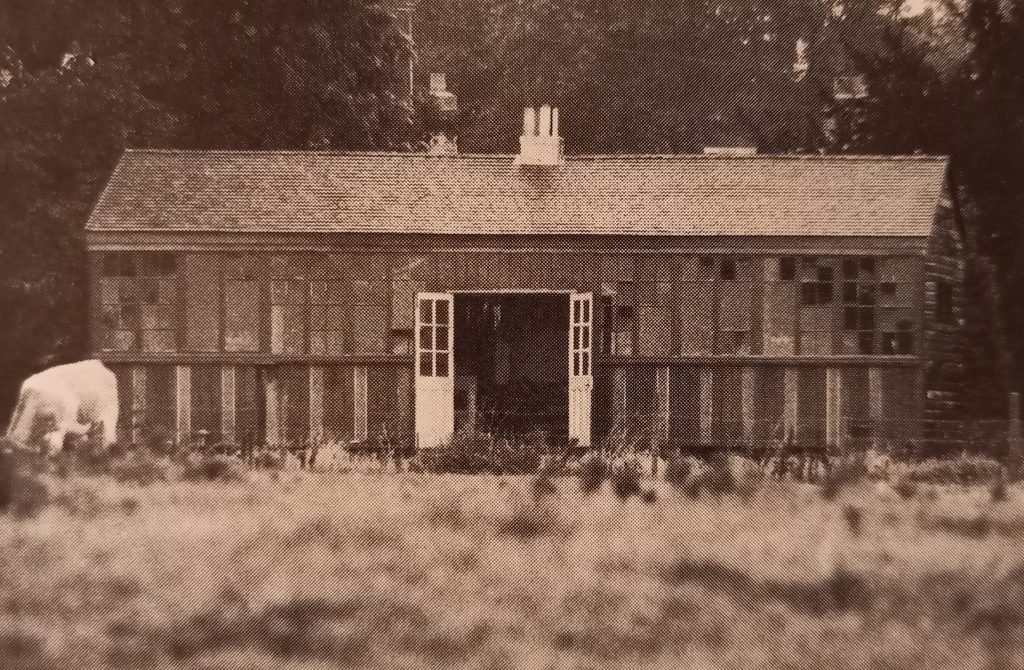

This is a piece from Crafts. No 42. Jan/Feb 1980. Elspeth Owen was asked to write about her pottery. At this time Owen had only been potting for eight years. She still has her studio in the same building in Grantchester, Cambridge.

When I meet people for the first time, they often say, “I’ve seen you before somewhere’’. There seems to be a similar reaction to my pots.

Passing child at craft market: “Are these Roman, Dad?” “Yes, that’s right’’; and, “Have these pots been dug up?”

I was born just before the war, and grew up with my head in the clouds (Schumann and Brahms — my mother plays the piano) and my feet shakily on the ground (air-raid shelters, ration books, and the bitter winter of 1947). I read History at Oxford, joined the Women’s Liberation Movement, began a training in psychotherapy, taught in a village school, and helped bring up two boys.

I began to make pots about eight years ago. I think my original intention in going to pottery evening classes in Cambridge was to dodge one supper-and-bedtime ritual in the week. But then I saw Dan Arbeid making his pots on television, and I started to pay more attention to the clay. During the following winter, the evening classes were taken by Zoé Ellison, who showed us slides of Cretan pots and looked very carefully at what I made. Then I began to look closely at pots in the American Indian section of the anthropological museum in Cambridge and at pictures of the work of Ruth Duckworth and of Gillian Lowdnes. ‘

From the start, my intentions were simultaneously subversive and integrating — I was out to have fun. I found my interest in the processes of making focussed and encouraged by reading Seonaid Robertson’s Rosegarden and Labyrinth and Paulus Behrenson’s Making One’s Way With Clay, and by looking at Arp’s paintings and sculpture, mushrooms and decaying fruit, Ewen Henderson’s pots, the insides of people’s rooms, and geological photographs.

The shapes I originally thought of making were tall cylinders and big coiled bins. None have appeared. Instead, I developed pinched forms, using a smooth stoneware clay. I tried using porcelain, but the shapes became too frilly, so I abandoned it. Accidents (not the same thing as mistakes) are part of the development of ideas – you have to keep alert so as not to miss a good one. Out of doors once, the grogged clay cracked, the result of warm air, the grog, and the fact that I was pushing the shape out from inside the ball of clay. What interested me was that the cracks made the form look as if it was still moving after it had been fired. This one accident led to a whole range of experiments with surface texture, cracking, splitting, and curling back the clay.

I want the decoration of pots to be inherent rather than applied. I add oxides into the clay to colour it, rather than painting or glazing on the surface. Decorative features are part of the shape: ridges are traces of movements made by my left hand at an early stage of raising the clay; from ridged pots developed strata pots, using layers of different coloured clays. The joins between colours and the breaking of lines interest me as a way of making movements, both vertical and horizontal. In New Guinea, we had an expression, “Let’s see your difference”, meaning the clearly visible yet blurred line on the body between suntanned and paler skin.

Recently, I have allowed the pots to come nearer to losing their balance. A slipped disc affects my own, and the discomfort I feel when my spine is out of place is contained in those pots which are nearest to collapse. These shapes are trying to give form to paradoxes: still/moving; open/closed; fragile/tough; angry/comforting. The contrariness also characterises my working method, since although I am right-handed, my left hand controls the forming of the pinched pots. I have started to use a bat to beat out shapes forcibly with my right hand, making pots which suggest their axes veering to left and right. Next, I would like to make pots that have the confidence of being made with both hands equally.