It is not easy for us to experience the shock of new things. At our fingers today we can type into the internet anything from Japanese Flute Music to American desert road signs and get the answers we expect. Television also exposed us to the world and so now, few things shock us. But try to think what you might have felt seeing an impressionist painting for the first time, if you had only been surrounded by Titian’s; or the wartime work of Paul Nash would have said to you if you had been surrounded by Constable paintings all your life? And where did you see these new paintings, was it in a gallery or in the press with an editorial of the erosion of society? Pick up any book on art history textbook and you won’t find anything considered modern in there until the mid 1920s.

John Constable – Wivenhoe Park, Essex, 1816

Paul Nash – The Ypres Salient at Night, 1918

This rejection of a fear of the new was felt by Frank Rutter, who in 1905, set up the French Impressionist Fund, with the support of the Sunday Times. This fund was open to the public to donate to, for the acquisition of an impressionist painting to be given to the National Gallery. Contributions slowly mounted up to £160, sufficient at that time to buy a top class Impressionist painting. This was mostly supported by the intellectual circles of London, from Virginia Woolf to Sickert. Rutter’s choice of painting to be picked was Monet’s Vétheuil: Sunshine and Snow, however the National Gallery did not accept work by living artists in 1905; and the gallery trustees also found Manet, Sisley and Pissarro, who were all too advanced. Rutter wrote: “They were certainly dead – but they had not been dead long enough for England”, adding “I nearly wept with disappointment.” The compromise was Eugène Boudin’s Entrance to Trouville Harbour, 1888. The National Gallery accepted this painting, although Rutter didn’t believe he was a true Impressionist, being at the start of the movement, but he compromised to get something rather than nothing, in the collection.

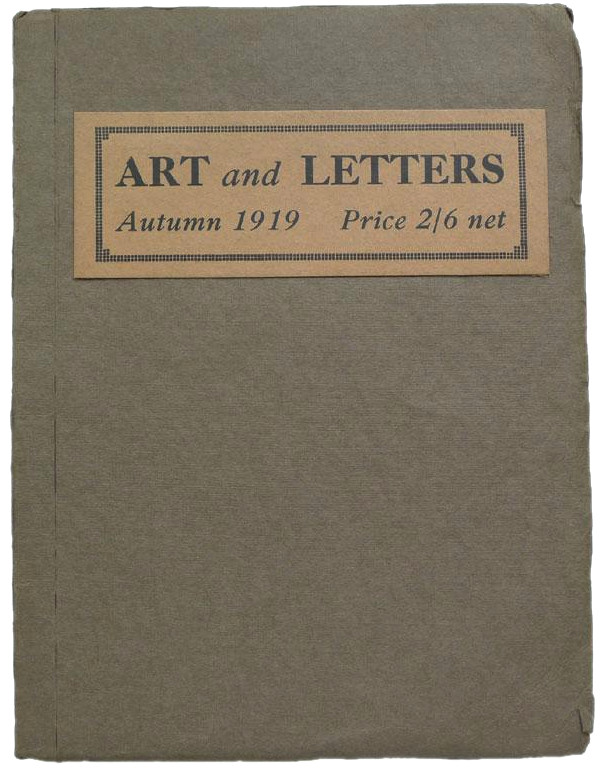

In the 1920s art galleries were also not free to enter, and were mostly obsessed with paintings from 100 years in the past. I think it is fair to say the public of Britain was not an engaged with the art world and so that, and so without the demand of an audience, there was no reason to change in the hanging of galleries; it was still an old-boy-network. For the modernists, their efforts of self promotion was to mix collectively in magazines that era. These mostly feature, poetry, pictures and prose. They also have an underground feeling, from Blast to Words and Letters, they all have the look of 1970s punk zines, cheap paperbound magazines done on a small press or duplicator.

However, the vibrations and shockwaves of Post-Impressionism and the modernist movements of the First World War (Vortist, Futurist, Dadaism) had been washed around in an ocean of ideas, and these lapped like water at the feet of the art students of the 1920s. From this era of artists, the new ideas formed into two camps: the minimal modernists and the maximalist surrealists.

The modernists were mostly British. The most accoladed of these young artists today are Henry Moore, Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, who took the ideas of primitive sculptures and ethnographic items and thought about what modernism really was by rejecting was it wasn’t. Though the teaching of the British art schools at this time still was looking to Italy and Europe for definitions of aspiration, many of these students had all been aware of Egyptian and pre-Columbian sculpture from local museums and magazines, and they had observed the same effects of those on Impressionist painters. It is also very likely with all the colonial propaganda of the British Empire, they were more exposed to the ancient worlds and tribalism of Africa, though with empirical projections of the ‘savage’ than of aboriginal artists. But we know Hepworth and Moore most certainly observed ancient artifacts during 1921 in the British Museum, Moore making hundreds of sketches and after learning how to carve sculpture, would reference these inspirations.

These young artists wouldn’t have made it alone. Older artists like Picasso were getting public attention and these young students were all championed by the art critic and poet, Herbert Read who was their life-long supporter. The British students had exhibitions and became part of the 7&5 Society and that was a nucleus for what was hip and happening in the avant garde art world in 1934 and 35; though the exhibitions they had were not sensations, they focused the press attention on this group and the movement looked more mainstream as a group.

At attitudes of the British public to art had changed in the 1930s, but by this point, modernism wasn’t so new, and art deco white sugarcube houses were appearing all over the country. Magazines also were hungry for content and twenty years on since the First World War, these ideas had become palatable and intriguing to their readers. When Henry Moore became an official war artists during the Second World War he was already famous by this point. I think it was Moore’s shelter scenes of the London Underground (as make-do bomb shelters) that added a level of emptaphy with the public and helped elevate his contemporaries after the war.