This post started with me looking at the April 1947 edition of Lilliput where the artical Portrait of a Neighbourhood, has paintings by James Boswell with text by Eric Hobsbawm, the left wing historian. The text intrigued me, as it was based around Boswell’s paintings, but mostly it is that I had seen the paintings used elsewhere before, but more on that later.

Hobsbawm’s examination of Camden.

Camden Town, the subject (of the four pictures James Boswell has painted for Lilliput) is the western outpost of the East End of London, and does not exist officially. No authority recognises it. All that can be said about its boundaries – for it is real enough – is that they run somewhere between the Euston Road and the black, rat-ridden Grand Union Canal, the Nash terraces in Regent’s Park and the great railway jungle of King’s Cross, Euston and St. Pancras. It is impossible to be more definite, for there is no Camden Town except in-so-far as people say they live there, and not, say, in Kentish ‘Town or King’s Cross or Chalk Farm. It includes all the people who shop in the High Street and Parkway, who go to the Gaumont or the Plaza or the Bedford Music Hall, who watch the crowds streaming to the Zoo.

How many? In all some 30,000, practically all shockingly housed. In the borough of St. Pancras in which Camden Town falls 17% of the men work in transport – mainly railways, 21%. in shops, restaurants, barber parlours and the like, 6% in metals. 18% of its women are: servants, waitresses and attendants, 11% clerks, typists and shop-assistants, and 52%, stay at home. Just over half work in the area. No doubt a good few of the 97 suicides (40 by gas), the 3 murders and 2 manslaughters of St. Pancras in the last year (when they counted such things) belonged to Camden Town.

There is nothing monumental or historic about Camden Town. Its great buildings are the pseudo-Egyptian Black Cat Cigarette factory, the barque music-hall, and the austere red brick baronial of the Rowton House lodgings for single working men. It is Victorian, except for the south-west, now blitzed and slum-cleared, and the beautiful grey, black and yellow Mornington Crescent. The Irish, with their nose for Georgian architecture, have settled there, and the coloured seamen drink in the pub at the corner, where they can see the statue of Richard Cobden, the only man in Camden Town with a monument.

What gives Camden Town its special air is simply the fact that its ordinariness is slightly démodé. Somehow it has stuck fast in the period when Sickert painted it, and Bernard Shaw campaigned to get it to elect him to the L.C.C. A few of the worst slums have been cleared, and there is better lighting. Its skilled trades are still old-fashioned – making pianos, organs, bagpipes and furniture. It has the street-crowds, the stalls of oranges, whelks and jellied eels, the odd jobs, the smell, the music-hall gilt and the greasy soot which the LNER and the LMS spread impartially over it. It isn’t as flamboyant as Stepney or Shoreditch, or as grim as Canning Town; it is just ordinary. That is why Boswell’s pictures show its people doing nothing specially Camden Townish, but simply the sort of things that are being done in scores of neighbourhoods in Inner London.

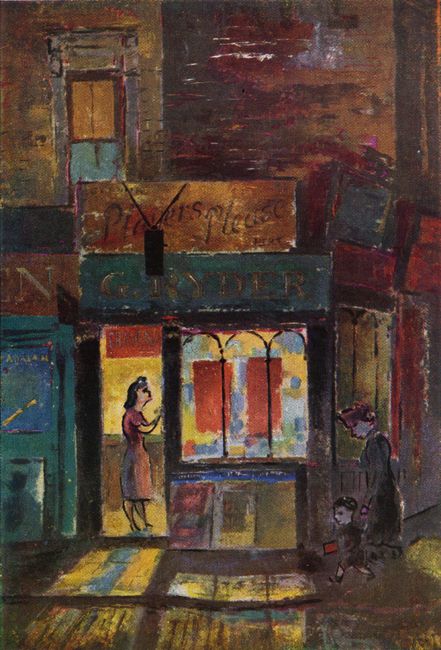

That stationer and tobacconist in his first picture, Little Gold Mine, for instance, is no different from other, once struggling shops. He sells maybe 5-600 daily papers (two or three dozen of them Irish, if he’s in that area), and makes his money on the tobacco. He stocks soft drinks, possibly sweets, certainly racing tips; works the shop with his wife, who handled it by herself when he was in the forces. He is probably an agent for a bookie. If he had a food shop, especially one that sold pies and sandwiches, he would do even better. One made enough in a year’s business to buy another shop. There is money about, and not enough on which to spend it, and anything sells in Camden Town. If it comes to that, everything is for sale, one way or another, within a 500 yards radius of the tube station: radios, pet monkeys, whisky, pictures of saints, model airplanes, artichokes, the works of Engels (who used to pass through regularly on his visits to Marx, stopping for a drink at the Mother Shipton).

James Boswell – Little Gold Mine

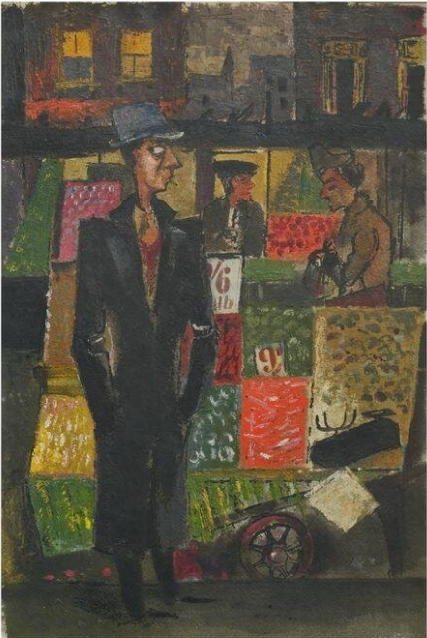

James Boswell – Private Enterprise

Another group which is not complaining is that of the street-traders like the spiv in Private Enterprise. The war has been the making of them. Previously many depended on ”governors” from whom they hired the, barrows (2/6 a week), and who bought for them and took a 33.5% share; or on moneylenders who helped them over the winter, when there were no sales. Now every man with a regular licence has an allocation of the rationed goods —oranges for instance; winter sales are brisk, and the “governors”’ are said to have lost much of their hold. Overheads have of course gone up: a barrow may be £1 & week or more, paper-bags have been up to 25′ a thousand, and a new man who wants to enter the trade may have a lot of other extras. Still, the wolf is kept from the door. Men have been known to pull in £20 a week, and if business is poor there is this and that to supplement it.

Camden Town is a smallish street-trading centre, and the 40-50 barrows are little more than half the pre-war strength. Their life is strictly balanced between a search for the best pitch and an eye on the coppers who move them on, Sooner or Later they all get hauled up; then they plead guilty. Why be awkward? For years the police have tried to make them sell in a side street, for years they have surged into the High Street. Once upon a time they sent a deputation to the Home Office, now they just sell, move off, and come back again. You can’t keep a good man down.

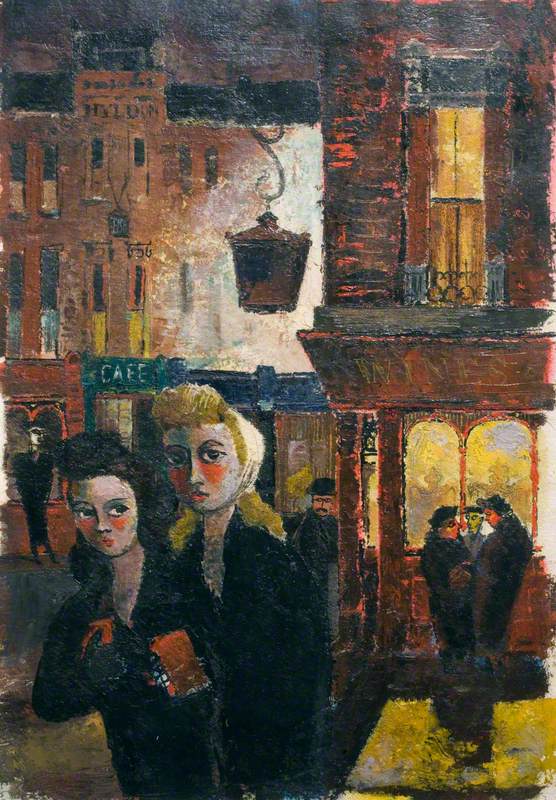

Boswell’s third picture, Saturday Night, shows one of the borough’s 267 pubs, one of its 304 restaurants and one of its 73 fried fish shops. The girls in front might work in Carreras cigarette factory or in a shop, and are on the way the pictures, or down the Hampstead Road towards Tottenham Court Road and the dance-halls, Perhaps even or even to Camden Town’s pride, the Music Hall. The café is probably run by a Cypriot who lives, with several thousand compatriots, just south of the Euston Road, the man against the walk might be an Irish builder, a railwayman, just possibly a demobbed Pole.

James Boswell – Saturday Night

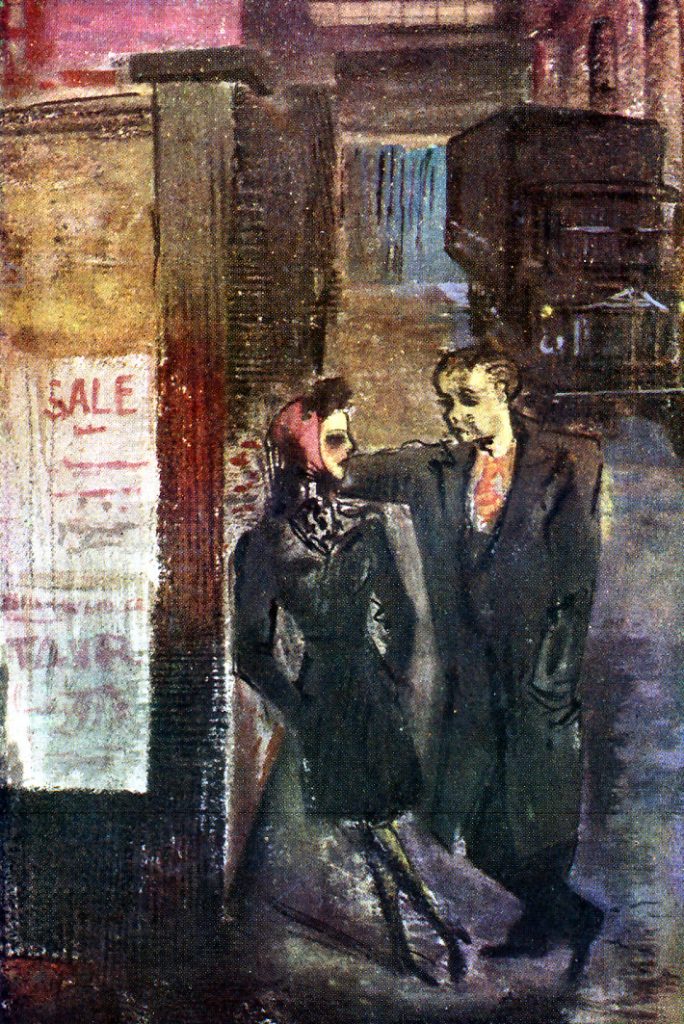

James Boswell – Spring Fever

Camden Town pubs run to brass and engraved glass rather than neon lights, though modernisation is creeping up in the main street. Later on in the evening the police will run in a few drunks, who, with shopbreakers and touts, provide most of the local crime. There are no pickings for classy criminals around. here. The couple in Spring Fever are probably in that alley because, like most Camden Towners, there is no room for them at home.

In summer they would go to Regent’s Park or up to Hampstead Heath. Had they married before the war, they could look forward to 1 3/4 rooms between them; now to less. If they have a child it may be one of the 70 out of every 1,000 who die before reaching the age of one in this district. Also the chances are just over 1 in 10 that it will be illegitimate. It is unlikely that they are worrying about this now. Spring blows into Camden Town from the hills of Highgate and Hampstead, and across from Regent’s Park, a few minutes away. The barrows will be shining with fruit, the pubs will be lit up. If the evening is quiet they will hear the northern trains and between them, faintly, the roaring of the animals in the Zoo.

About the images.

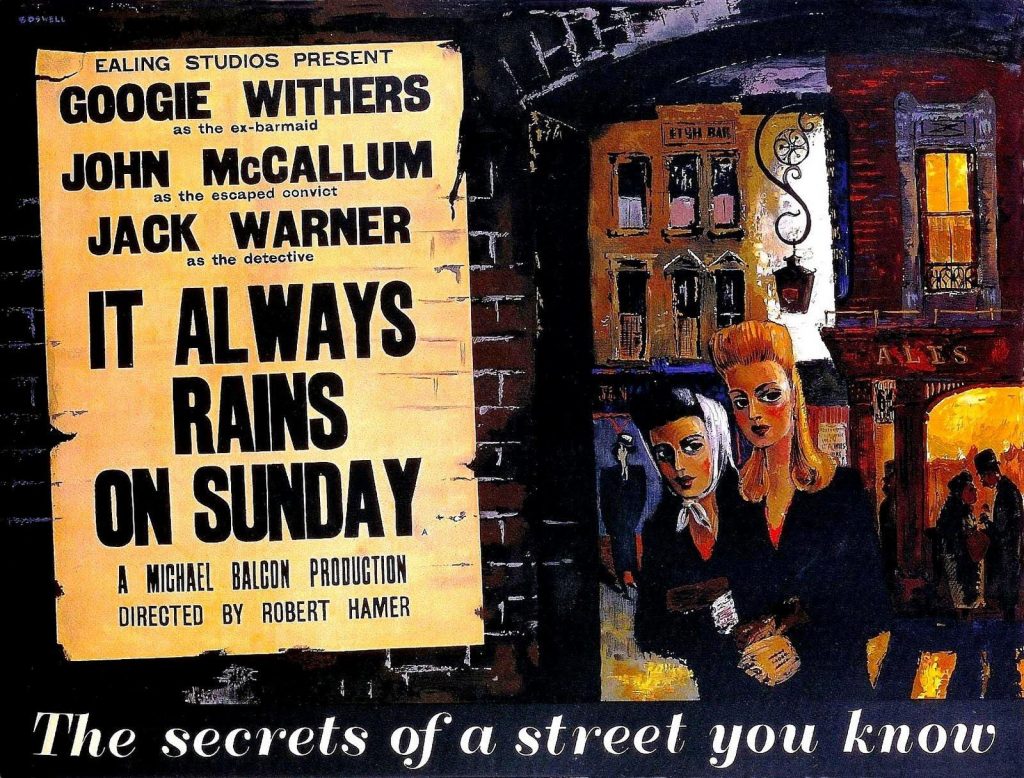

Now to address the images, according to his widow, Boswell has been painting these scenes of Camden Town for Ealing Studios to use on a poster for the movie It Always Rains on Sunday (1947). The painting Saturday Night is used for the poster (below) Boswell then made a collage of work to deliver to the studio with the added the arch and wall, printers at this time copied and translated designs, cleaned them up and really rearranged them however they wanted.

At this time in his life, Boswell was living in Hampstead with his Canadian wife and their daughter Sally. He was also the editor of Lilliput magazine for a time. The painting must have made a good impression as Boswell completed the others on the power of the poster.

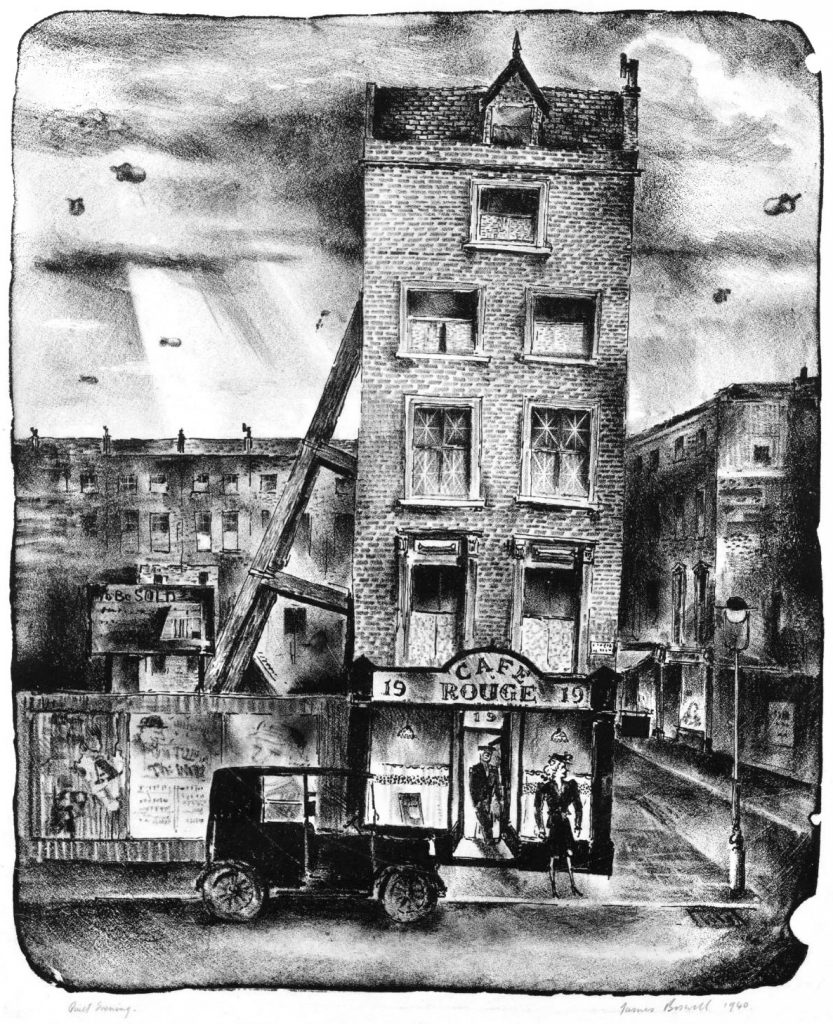

But Saturday Night wasn’t the only design I had seen before, on the front of the essay is a little drawing of a cafe. It appeared again in this lithograph produced in 1940 (I think likely designed for the AIA Everyman series, but not used). Being a print and drawn to a lithographic stone, the sketch would have looked the same until he went to print it, then it would be printed backwards. Thankfully he must have been aware of this as he put the Cafe Rouge and numbers the correct way around. (But you would be amazed how many artists and students forget).

James Boswell –

Quiet Evening

1940

By the look of it, the building must have had some bomb damage next door with the props up from the recently demolished neighbour. The building has got taller in the lithograph and given it was printed in 1940, it was likely so the building would stand against the barrage balloons in the background.

As a bonus and interesting fact about the movie, It Always Rains on Sundays, is that the title card has a picture by Barnett Freedman behind it.