This essay comes from the Shell Guide to England, 1970. The Shell book I actually found for free in a shipping trunk. Inside are many starchy pieces of text on the English landscape and it gets a little dry at times. I guess even when it was published the essays were written to the wrong market, being more historical than artistic and most people would know a great deal of it. However, the most entertaining essay in the book is by Barbara Jones who uses all of her wisdom from her Follies & Grottoes books to give a brief account of the history of follies for the layman and where you might find some exciting examples. My copy of Follies & Grottoes is well read, it is exlibris of Laurence Whistler and found for a fiver. The illustrations here come from the two editions of it.

Barbara Jones – Follies & Grottoes, 1953 and enlarged in 1974.

The English love to break down the natural scene. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the areas of natural heath and scrub left untouched by medieval husbandry were vigorously taken in hand and built upon, gardened, afforested and landscaped, most of England was arranged by man. In the nineteenth century the whole country was netted over with railways, and the cities grew; but, in fact, the scene was not altered very much. In this century we have come to accept that scene as natural, as the country”. We in our turn are trying to break it down, with motorways, industrial sites and new cities.

At all times since the end of the Tudor wars there have been English landowners, with anything from a ducal estate to a suburban front garden, who have not been content with other people’s ideas of breakdown, with the ordinary thing. Even if they have been able to commission idiosyncratic houses from great architects, they have still wanted something more, something wilder. The results of these impulses are scattered all over the country, and are called by the other English “follies”.

Follies take many forms. We may discount at once the follies in name alone, houses of which neighbours disapproved, or houses built too far from water, or with too little money to finish them, and also various clumps and belts of trees (the word was corrupted from feuillée). And the ordinary garden house, temple or gazebo does not qualify either. The element of eccentricity is essential; follies are fantastic, a little crazy in desire or design. Architecture is building for shelter; follies are building for building, a purer art. Towers and obelisks build upwards; labyrinths and tunnels build down. Other follies are aggregates of unlikely materials, abstractions of shells and minerals, bark and branches, nearer sculpture than architecture, the desire to amass solids in space.

The earliest folly I have found is Freston Tower in Suffolk, built in the middle of the sixteenth century, a brick tower on the banks of the River Orwell, near Ipswich. At the end of the century Rushton Triangular Lodge was built in Northamptonshire by Sir Thomas Tresham. Everything is in threes: the plan is triangular, each wall three times three times three feet, three sets of three-by-three triangles on top of the walls; three floors; three windows each side on each floor; trefoils and triangular pinnacles. Ten miles away at Lyveden is the shell of Tresham’s house, extending the arithmetic of three to five, seven and nine. More follies and conceits, and some tunnels, were built in the next century, mostly surviving only in visitors’ accounts of them, though there is a sinister temple of bark nailed over wood at Exton’ Park in Rutland, and there are fine grotto rooms of stone and shells at Skipton in Yorkshire and at Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire.

In the eighteenth century follies became fashionable as well as eccentric; a nobleman’s estate positively needed one. Towers, tunnels, and grottoes continued in production, and all sorts of new follies were invented – sham castles and ruins, hermitages, labyrinths, obelisks, and eye-catchers. In the nineteenth century fewer follies were built, and those more by the rich than the noble, but druid circles were invented, and some superb folly gardens were laid out, with a curiosity round every corner. Late in the century fantastic gardening with broken china, slag, shells, flint, glass, coal, and coral became fashionable for the poor as well as for the rich. Only two or three dozen follies have been built in the twentieth century, but the little gardens continue, with gnomes added to the older materials.

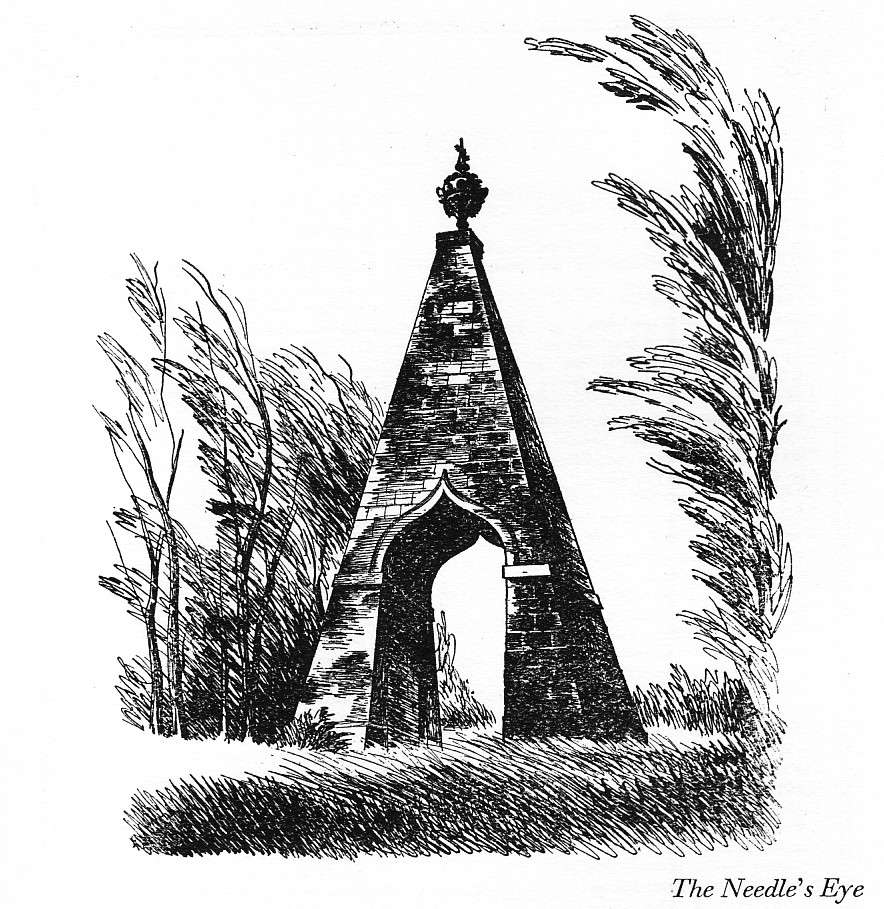

The commonest sort of folly, and the easiest to find, is that which is built upwards. There are a great many ordinary little ones, but there are also some magnificent towers, built to commemorate great happenings or to command great prospects. There is a nice triangular one in London, in Castlewood Park at Shooters Hill, 64 feet high, built in 1784 to the memory of Sir William James and to “Record the Conquest of the CASTLE OF SEVERNDROGG on the COAST of MALABAR which fell to his Superior Valour and able Conduct on the 2nd Day of April MDCCLV”. In the nineteenth century it was used for select parties, and now it is a tea shop. Another triangular folly is Haldon Belvedere, near Exeter, built by an ex-Governor of Madras, with a floor made of marble from Hyderabad, and really exquisite plaster work. At Wentworth Woodhouse in Yorkshire is Hoober Stand, 1748, a superb 100-foot soot-stained golden tower on a triangular plan, its sides tapering to a hexagonal lantern. It was built by Thomas, Marquis of Rockingham, in honour of George II. Nearby is Keppel’s Pillar, built by the 2nd Marquis in 1782 to commemorate the British Fleet at Ushant. It soars up, supporting nothing, an amazing 150 feet. Also nearby is the Needle’s Eye, a tall stone pyramid pierced by an ogival arch and crowned by a lovely urn, built, the story goes, for a crack whip to drive through after he had boasted that he could drive a coach and horses through the eye of a needle. At Wentworth Castle there are more conceits.

Many follies have good stories attached: you may be told that the builder is buried under the floor because he quarrelled with the parson, or is there standing on his head, or with his favourite horse under him. One man seems to have deserved all the stories: Mad Jack Fuller, who built a Needle, a Mausoleum, a Tower, a Rotunda, and an Observatory at Brightling in Sussex, and at Dallington a neat cone called the Sugar Loaf, to justify a night-time statement that he could see Dallington church spire from his dining-room window. In daylight this statement proved wrong, but he made a sham spire just over the skyline, to be right for his next dinner-party. Attached to his pyramid tomb is the most persistent of all the legends: that he is sit at table inside, with a bottle and a bird before him.

At Tong in Shropshire are some pyramids with no legends at all, perhaps because the builder George Durant said exactly what everything was for – and imagination could invent nothing stranger. “Quaint buildings, monuments with hieroglyphs, and inscriptions alike to deceased friends, eternity, and favourite animals – were then to be found on every path of the demesne”, says an old local guidebook.

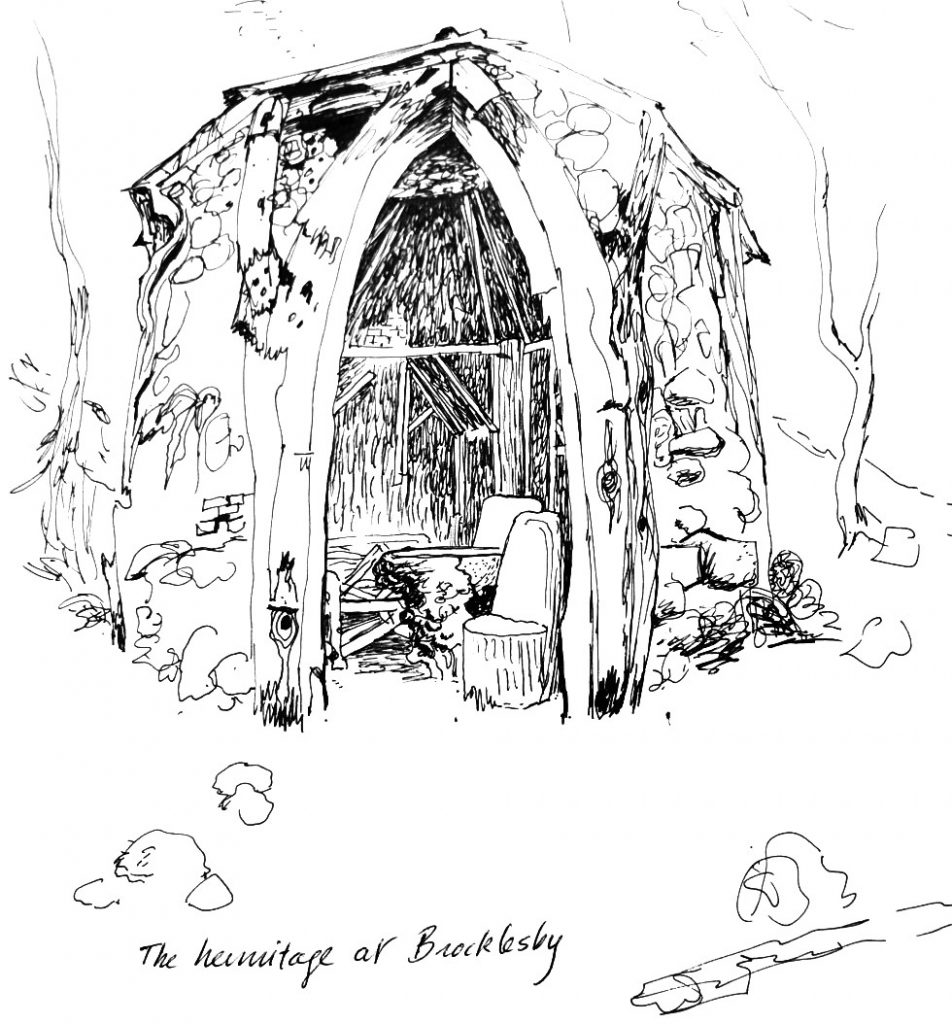

Pyramidal gate-piers are carved as though bound with heavy ropes, and such objects as lamps and snails are carved in panels on the walls. A gazebo called The Pulpit has animals and snakes. On a nearby farm there is also an Egyptian Aviary, a pyramidal hen-house labelled AB OVO. Durant was one of the few gentlemen of his time who not only longed to have a hermit in the grounds to show to visitors, but achieved a very contented one, for a gentleman who had fallen on hard times lived in a cave at Tong until he died in 1822. The contemporary terms for the employment of hermits were usually much alike: a cave (or a rustic hermitage of roots, branches and knotty wood) was provided, and a hermit was advertised for, to serve a period of seven years, living secluded, with hair long, and nails unclipped, never speaking, with good food sent down from the house daily. But it seems that few people are even mock hermits by nature, or few people know how to employ one kindly. One gentleman was forced to use a wax image; and there are many records of early failure – the hermit went away, or he was found drinking in the village and dismissed. One known success, however, was the Hermit Finch, whose Sanctuary lies down in the woods of the park at Burley on the Hill in Rutland, preserved with most remarkable and imaginative rustic architecture and furniture, a pebble-and-knuckle-bone floor, and even the hermit’s sacking bed.

The desire to dig downwards is rarer than the desire to build up. It is also much more expensive; so the tunnellers had to be very rich or very determined. The 5th Duke of Portland’s underground rooms at Welbeck are the most famous mole-works. The Duke was said to speak willingly only to the men who dug the tunnels. Most excavations have an air of sadness. Many have walls of bare earth, or lined with cement, or strung along with a handful of cockle shells. But they were highly esteemed the last century, for the Catacombs at High Beech in Epping Forest were a pleasure resort. They are a wild descent into the dark earth of huge blocks of masonry said to have come from Chelmsford gaol, hidden under the garden. As well as the plain tunnels of compulsive digging, there are excavations of great beauty in the form of grottoes, where the surface has been decorated with glittering minerals, exotic shells, fossils, tufa – all the natural objects that became commonly wonderful in the eighteenth century. I have referred to the shell rooms at Skipton and Woburn; in both of these there is contemporary architecture with an overlay of shells. In the eighteenth century this style continued in fashion, greatly refined, culminating in the exquisite Shell House made by the 2nd Duchess of Richmond at Goodwood in Sussex. True grottoes, though not always underground, look like caves under the sea, spar and shells arranged in waves and stalactites. We have the name of Josiah Lane as builder, with his son, of a series of superb grottoes – at St Giles House, Cranborne, in Dorset, Fonthill in Wiltshire, St Anne’s Hill and Pain’s Hill in Surrey, amongst others. The two-roomed grotto at Wimborne St Giles is in the park and is shown with the house; it has been restored and is probably the finest shellwork of this sort that we have, a wonderful composition of surfaces and colours, the insides of shells gleaming against the

duller backs, small shells offsetting large.

At Stourhead in Wiltshire the National Trust owns a famous grotto, large and formal, built round one of the headwaters of the Stour, with fine statues of a nymph and a river-god. The walk round the lake runs through the grotto, a green, cool melancholy contrast to the splendid Capability Brown landscaping. Another remarkable grotto was built by Thomas Goldney in his garden on top of Clifton gorge at Bristol, with a cascade leaping from an urn held by Neptune, echoes from the wild water, a Lions’ Den and fine shells. All these grottoes are professional work, and look it, but by the beginning of the nineteenth century only amateur grotto-builders remained. The fashion spread wide; most towns, especially those by the seaside, have a bit of shellwork somewhere. There is a big one at Margate, probably made by two brothers called Bowles in an existing excavation. It was lost to sight for about thirty years, and found again in 1834 or 1835 by a schoolmaster’s son digging a duckpond. There is

almost no fantastic origin that has not been claimed for it – Cretans, Druids, even Tibetans, are supposed to have built it, and the simple amateur shellwork has been interpreted in a hundred gnostic symbols: we are a romantic-minded race. Druids were very fashionable in the first quarter of the century; there is a good sham Circle on the Yorkshire moors near Masham, a real prehistoric temple moved from Jersey to a back garden in Henley-on-Thames, and a Druids’ Table among the bone grottoes and bone-lined caves at Banwell on Mendip in Somerset, elaborated during the years after 1824 by the Bishop of Bath and Wells over and down some mine-shafts and two natural caves with stalactites and stalagmites. Ancient animal bones were ready on the floor, and the Bishop made the most of them.

Back to the eighteenth century, and back above ground. The Middle Ages and the Barons’ Wars became very modish, and Gothic architecture was admired again, not often for gentlemen’s houses, in spite of Walpole at Strawberry Hill, but certainly for follies. Suddenly hundreds of gentlemen wanted to see the ruins of a Gothic castle crumbling at a suitable distance from the house. A few of them had real ones; the others plunged into the fun of building fakes. Some of the sham castles were ruinous in design, like that at Wimpole in Cambridgeshire; some rapidly became so through being knocked up in a hurry or on the cheap; and some were built very crisp and new like Sanderson Miller’s Sham Castle outside Bath, a façade rising about forty feet on a hill-top, flat as a piece of scenery, which indeed it is, a wall without a room. Some castles were in fact made of painted canvas on wooden frames, so great was the scramble to get them up. Some were rich with Gothic detail, trefoils and quatrefoils, and castellations and arrow slits, but often reproduced on an absurdly large scale as there was no need to consider the strength of the wall, and defence could become decoration. Others were so ungothic that they could not be called castles; they were curious spiky constructions, often of flint, that were given names used for no other architecture, like eye-catcher, terminal, conceit, or vista-closer. Many of them were undoubtedly designed by eager amateurs of the arts, and put up by the estate workers; but a timid amateur could find plenty of help in the dozens of books on the Picturesque or the Grotesque that were published, with illustrations, plans, elevations and dimensions of every variety of hut, retreat, cascade, bathhouse, mosque and pagoda, from trifles made with Rude Branches to enormous Mauresque Pavilions beyond the Do-It-Yourself of all but the greatest estates.

Some people, having built one folly, went on. Hawkstone in Shropshire was an estate with many fine follies. The hermitage, with mock hermit, and an ornamental windmill have disappeared, but half a dozen survive, including a marvellous labyrinth that rises to the sunlight on top of a rocky bluff. Stourhead has a Rustic Convent, St Peter’s Pump, and Alfred’s Tower, as well as the grotto, and West Wycombe in Buckinghamshire has a Mausoleum, St Crispin’s Cottages – built to look like a church from the house – a Sham Lodge, and caves, now with son et lumière, Today, the folly impulse is concentrated in the small gardens, the miniature model villages that have succeeded the real ones of the rich, and a continuing tradition of topiary, we still have such gardens as the breath-taking solid geometry clipped from yew at Levens in Westmorland, that has been clipped since 1689. And there is a new one in Wolverhampton that has privet topiary of sixteen Scotch terriers, two cats and a rat.