This artical appeared in Lilliput magazine in 1944 by Thomas Burke. It is a brief biography of Simeon Solomon; the artist rejected by society because of his conviction for sodomy in 1873 (sentenced to Hard labour) and in ’74, when he was arrested in Paris for soliciting men and spent three months in a Paris jail.

From a wealthy family his brother Abraham was an artist as well as his sister Rebecca. His lifestyle bought him to alcoholism and he became a vagrant despite his family connections. He was a beautiful and talented young man.

Nobody pays much attention to the work of pavement artists, or to the “artists” themselves. So nobody, passing along Bayswater Road in the first years of this century, paid much attention to a blotchy, unkempt screever and his coloured chalk drawings. Nobody even noticed that the drawings had an assured ease not usual in the work of screevers. Pennies in the cap were few.

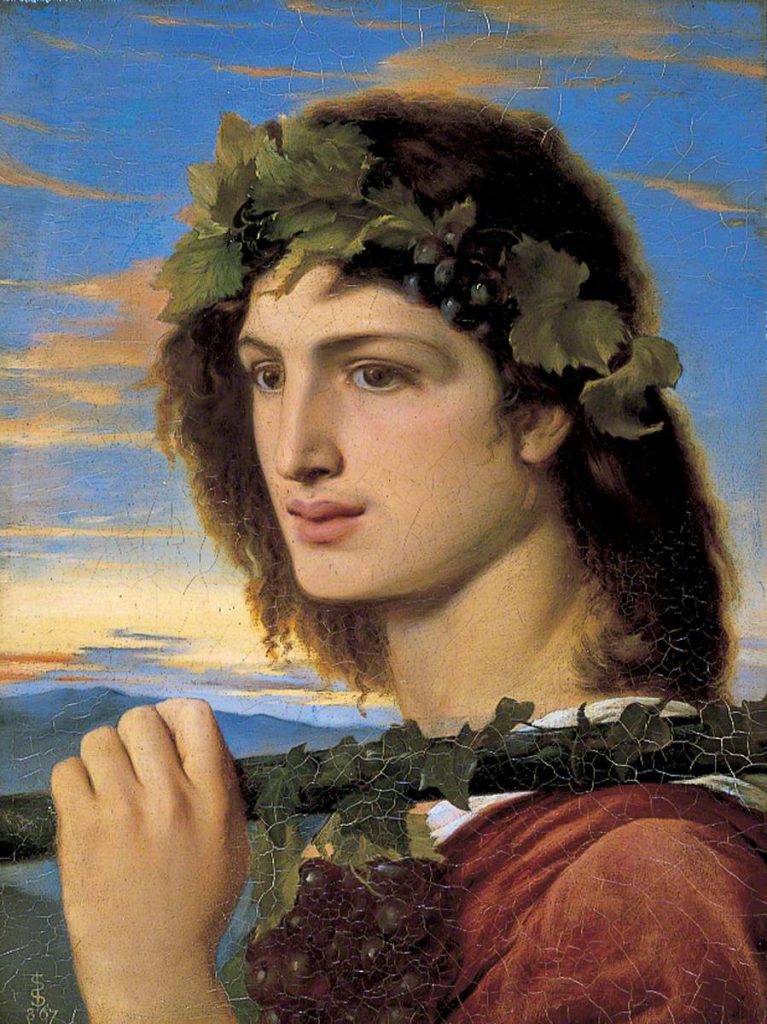

Simeon Solomon – Bacchus, 1867

But if people had been better informed they would surely have given more than a casual glance to the man who had been hung in the Academy for twelve consecutive years, and had been an admired friend of Burne-Jones, Walter Pater and Swinburne. For Simeon Solomon was an artist whose name appears, always with epithets of regret and compassion, in many volumes of the art and literary memoirs of the later nineteenth century.

A queer story, his; one of those stories of wreckage of bright hopes of which the nineteenth century holds so many; among them Thomas Dermody, John Mitford, Charles Whitehead, James Thomson (B.V.) and Ernest Dowson.

With most of them the cause was drink; for the drink of the nineteenth century was of more fiery and mordant temper than the drink of this century which, if it has fewer geniuses, has fever stories of wreckage. With Simeon Solomon the causes were many and obscure.

He was born in Shoreditch, son of a Jewish hatter. Drawing and painting came instinctively to him at an early age. At 15 he entered the Royal Academy Schools, and was first hung at the annual exhibition when he was 17. The subject of that first picture, like the subjects of most of his pictures, was taken from the Old Testament, and its manner was that now known as Pre-Raphaelite. At this time he is described as a handsome graceful figure, with red hair, an exquisite profile, and brilliant eyes. His appearance alone made people notice him, and when his work was seen he won the acclamation of many of the alert, among them Swinburne and Pater; white Burne-Jones, writing years latter in a perhaps over-generous mood, said that “Simeon Solomon was the greatest artist of us all.”

Simeon Solomon – The Magic Crystal, 1878

Like many of the artists of that group he had a literary gift., and a rare little pamphlet of his – A Vision of Love Revealed in Sleep – May sometimes be turned up by the curious. Swinburne gave his work an enthusiastic review; Pater too admired it. Written in the rather inflated prose used by De Quincey, it records the wanderings of a spirit conducted through a land where he sees the figure of Love in different stages of suffering, caused by the wrongs and abuses inflicted on man. For some years Solomon was a vogue and a figure in intelligent circles. He was often Pater’s guest at Oxford he visited Lord Houghton (Monckton Milnes); stayed with Oscar Browning, then a master at Eton; and was much seen with Swinburne.

But he didn’t want his gifts or his personal beauty. He threw them to the dogs. The rot set in when he was about thirty. What caused it is not clear, but at that time it was not drink. It was something more serious; something that caused Oscar Browning , when he was talking him on a tour of the Italian galleries, to part company with him and come home alone. There are stories of drugs and of indiscreet aberrations. Unpleasant elements began to appear in his work, notably in those presenting ideas of love. Also, it became coarse and careless in treatment, and he repeated his subjects. Friends warned him against prostituting his genius. He ignored them.

His aberrations soon became too extreame even for Bohemia. Men began to withdraw from him, and his name began to be spoken in polite circles only in a pitying murmur. Swinburne not only broke with him; he spoke of him as “a thing abhorrent to man, woman and beast.”

The end of his vogue came as abruptly as it began. He had some fifteen years if success, prosperity and respect. Then he turned his back on it all, and deliberately lived the rest of his life as an exile, among the social outcasts.

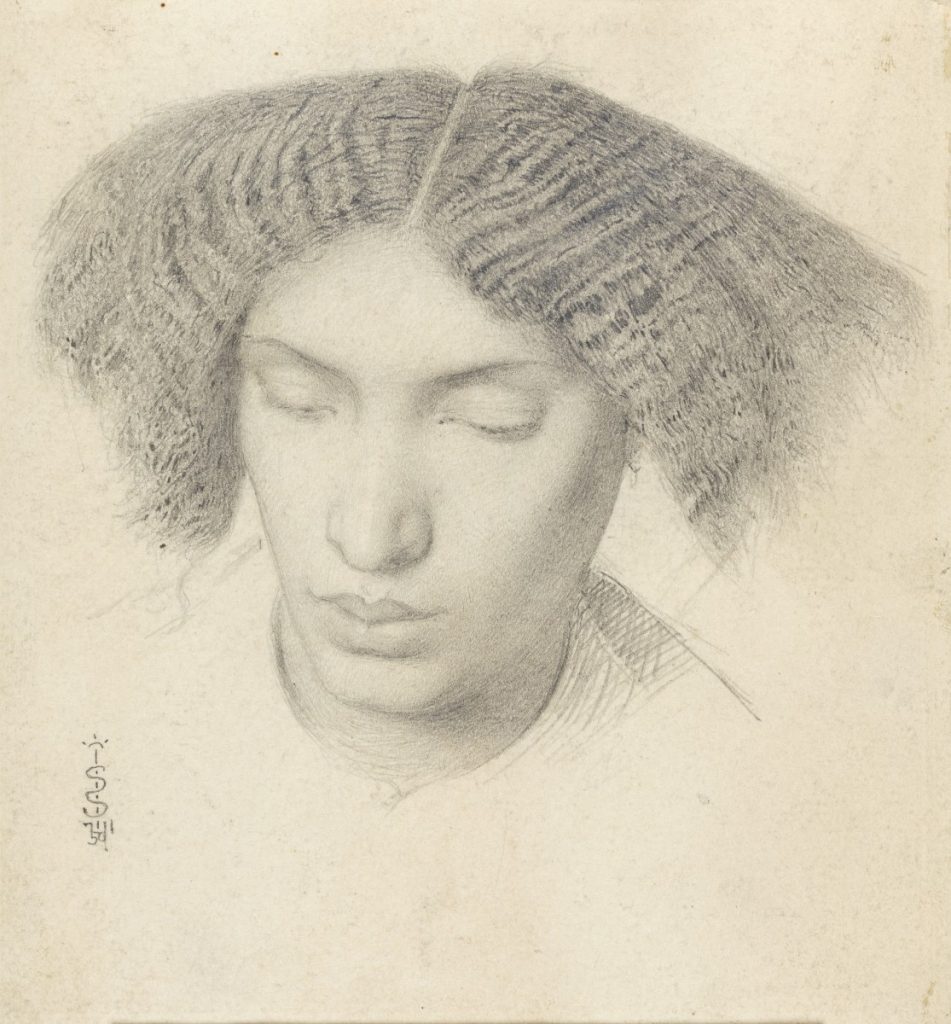

Simeon Solomon – Mrs Fanny Eaton, 1859

His conduct eventually led to a term in prison, but in prison he wrought no cure. His family got him into a mental home; that, too, was ineffectual. When he came out, many efforts were made to reclaim him. They were futile. By that time he had added drink to his other indulgences and seemed beyond hope. He was set up with clothes, a studio and a decent home. He never used the studio. He sold only the clothes and furniture and returned to the gutter.

Dealers were still willing to buy his work, and one or two supplied him with the necessary materials and small advances, though they could never rely on actually getting the drawings. But though he had lost all moral sense, he did not lose his good human feeling. For long periods he was an inmate of St. Giles Workhouse, and when he did deliver a drawing and collect the money, he would take some of the old workhouse boys for the day and bring them all home tight.

He was not above sponging on successful artists with whom he had once been equal, and there is a story that, having successfully touched a prosperous artist and noticed the rich contents of his home, he repaid the loan by coming back with one of his gutter friends, a professional burglar, and breaking in. But he and the burglar were both so drunk, and made so much noise, that they roused the artist. He came down, and found Simeon Soloman with the dining room silver dropping out of his pockets. He contented himself with kicking the once famous artist down the steps. For a time Solomon sold matches in the gutter at Whitechapel, but no more successful at that than as a pavement artist.

The decline and fall of a sensitive spirit is usually pitiful, but Soloman needs no pity. In his outcaste state he was quite happy, and seemed to enjoy the shabby freedom of rags and irresponsibility.

A friend of mine, one of the few living men who met him, told me of his first sight of him in the closing years. My friend, then a young man, saw a drawing in a Regent Street print shop, and was struck by it and bought it for three guineas. He had never heard of the artists, and asked the dealer who was this Simeon Solomon. The dealer said “If you look through the door you’ll see him.” My friend looked out to Regent Street, but could see no artist. He saw a ragged, decrepit old waif of the streets looking in the window, but nobody like an artist. He said “I don’t see anybody.” The dealer said “There – at the window. That’s Simeon Solomon, friend of Burne-Jones and Rossetti and Swinburne. He’s waiting till you’ve gone to come in and touch me for five bob on account.”

Somehow or other he supported this submerged and vagrant life for thirty years. He lingered on in drink and degradation till he was 64; til all those who had known him had forgotten him or presumed him dead. Then, one night in 1905, he was found unconscious on the pavement in Holborn, and was carried to his old home, St Giles Workhouse, and in its infirmary he died.

Tributes, to the genius which he threw away, are many. Even the respectable Oscar Browning, a reputed social snob, could say of this ruined outcast “He was a genius both in art and writing, and his name deserves to be remembered… I am proud to acknowledge that he was one of my friends.”