In this post I look at the artworks of events at Dunkirk in 1940. Some would have been sketched or observed on the day, others were painted with eye-witness reports and photographs. Many were finished in a studio in the weeks and months after.

On 10 May 1940, Germany invaded France and the Low Countries, pushing the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), along with French and Belgian troops, back to the French port of Dunkirk. A huge rescue, Operation ‘Dynamo’, was organised by the Royal Navy to get the troops off the beaches and back to Britain. ‡

‘Dynamo’ began on 26 May. Strong defences were established around Dunkirk, and the Royal Air Force sent all available aircraft to protect the evacuation. Over 800 naval vessels of all shapes and sizes helped to transport troops across the English Channel. The last British troops were evacuated on 3 June, with French forces covering their escape. Churchill and his advisers had expected that it would be possible to rescue only 20,000 to 30,000 men, but in all 338,000 troops, a third of them French, were rescued. Ninety thousand remained to be taken prisoner and the BEF left behind the bulk of its tanks and heavy guns. All resistance in Dunkirk ended at 9.30am on 4 June. ‡

When I saw the Richard Eurich picture below, the sea was so well painted it looked like glass. It was at an exhibition in the Queens House, Greenwich. It is a fantastic picture that viewed in a book or on the internet doesn’t comprehend. It was also used by the Navy as its Christmas card for 1940.

Richard Eurich – Withdrawal from Dunkirk, 1940

Charles Cundall – The Withdrawal from Dunkirk, 1940

John Spencer-Churchill – Dunkirk from the Bray Dunes, 1940

Below is a painting by Wilkinson who to my eye is the master of painting seascapes. He has a wonderful repertoire of boats and the lighting in this painting is a marvel. Though beautiful, it also shows the hellish chaos of the day.

Norman Wilkinson – The Little Ships at Dunkirk, 1940

The Little Ships at Dunkirk: June 1940, by Norman Wilkinson. The gently shelving beaches meant that large warships could only pick up soldiers from the town’s East Mole, a sea wall which extended into deep water, or send their boats on the beaches to collect them. To speed up the process, the British Admiralty appealed to the owners of small boats for help. These became known as the ‘little ships’. ‡

Newspaper with the small announcement under ‘War Artists’.

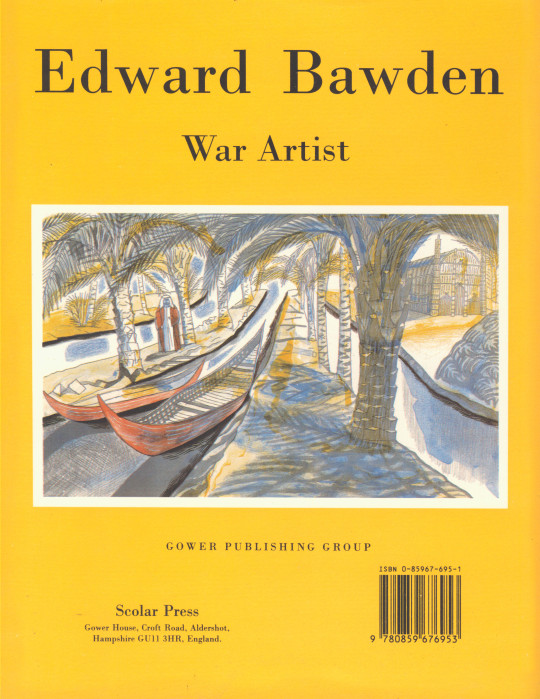

On Thursday, 7th March, 1940, three days before his 37th birthday, it was announced in the British papers that Edward Bawden and Barnett Freeman were to become Official War Artists on behalf of the British War Office.

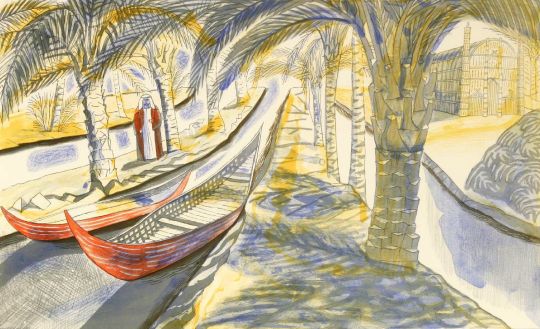

In the first days of April, Ardizzone (Edward) and Bawden took rooms for a while in the hotel Commerce in Arras, fussed over by a shared batman. They enjoyed the local wine and hospitality, before being billeted separately. Arras was dour, small and grey, It was also the GHQ for the British Army in France. †

Arras in France is just over fifty miles away on a map, from April to May the retreat to Dunkirk was rapid and not an inspiring start for a war artist. In this short time Bawden said he was passed from regiments and groups rapidly as none of them wanted the alien burden of an artist to deal with, but being on the move a lot may have prepared his sketching style ready for Dunkirk where rapid copy was needed.

On his way to Dunkirk, Bawden has rolled up his paintings in a cylindrical tin which he clutched under his arm. †

Approaching the port, he ditched all his equipment except his art materials (what would the Germans have done with them?) Marching into the town, they ran the gauntlet of ragged French soldiers jeering them. It discomforted him, as did the looters sweeping like locusts through abandoned houses. †

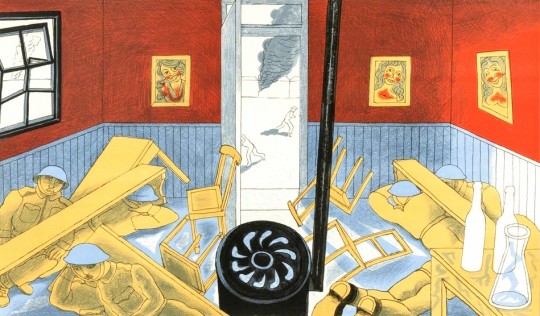

Edward Bawden – Dunkirk: Embarkation of Wounded, May 1940

Edward Bawden – Dunkirk – The New World, 1940

Edward Bawden – Boys Serving Coffee, Dunkirk, 1940.

He reached the quayside in the company of a Canadian major, and they watched with dismay the frantic self-preservation of a group of British generals on the Dunkirk quayside, the swagger sticks pointing at likely boats bound for England. He turned to the major, with a wry smile. ‘Rats always go first’ he said. †

Edward Bawden – Dunkirk – Embarkation of Wounded, 1940

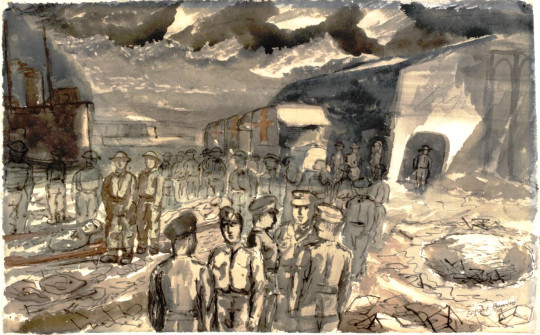

Edward Bawden – The Quay at Dunkirk, 1940.

In the watercolour above, notice the fires along the jetty. The men in the foreground descending into a air-raid shelter and the bomb craters on the ground. The air raid shelter is likely to be the same one below, but in the chaos who could tell.

Edward Bawden – The Entrance to an Air Raid Shelter, Dunkirk, 1940

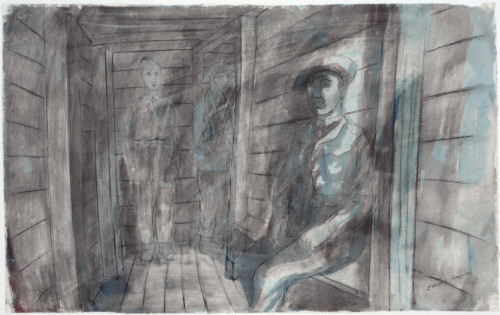

Edward Bawden – In an Air Raid Shelter, Dunkirk: Bombs are dropping, 1940

† The Sketchbook War by Richard Knott, 2013 978-0752489230

‡ Imperial War Museum – Dunkirk