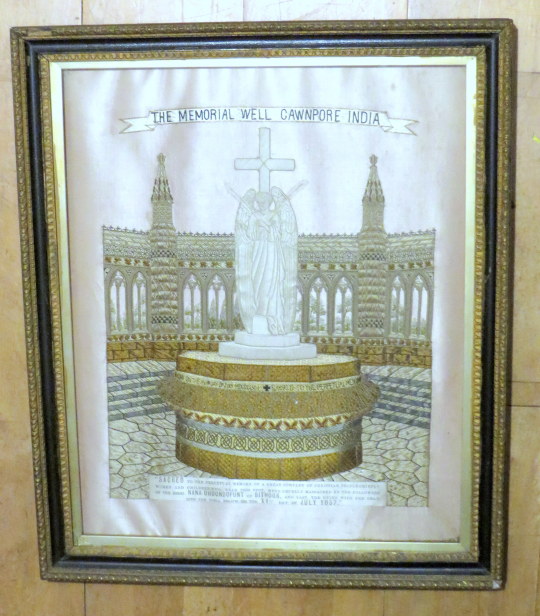

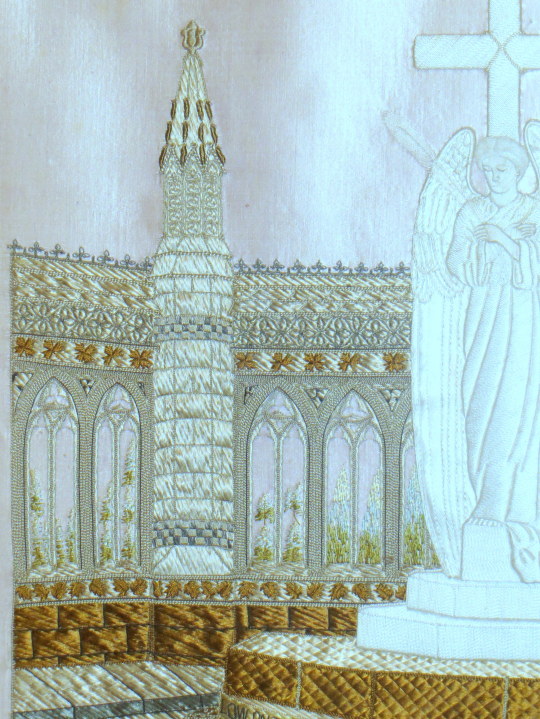

I was in an antique shop in Cambridge just before Christmas when I saw an embroidery on the wall. It was a Victorian memorial piece made from silk and the detail of it was stunning. It was done in the memory of the victims of Cawnpore. Below, in short, is the story of the Indian mutiny.

The large embroidery for the victims of Cawnpore.

Cawnpore was a major crossing point of the Ganges and Grand Trunk Canal, and an important junction where the Grand Trunk Road and the road from Jhansi to Lucknow crossed. Cawnpore was to become a vitally important garrison town for the British, straddling key communication lines.

In 1857 it was garrisoned by four regiments of native infantry and a European battery of artillery and was commanded by General Sir Hugh Wheeler. Wheeler had served in India most of his life, had an Indian wife and a gross overconfidence in the loyalty of the sepoys under his command.

Sepoys were the native, Indian soldiers who served in the army of the British East India Company. On June 27th, 1857, in Cawnpore, India, a British garrison with many women and children, under siege, were offered safe passage and sanctuary. Instead, they were betrayed and butchered. The surviving women and children were later hacked to death. The British retribution, when it came, was unrelentingly severe.

A View of Cawnpore, India, 1858) †

There was one complicating factor in the area that would come back to haunt Wheeler and the garrison. Nana Sahib was the adopted heir of the last great Mahratta king Baji Rao.

Unfortunately for Nana Sahib, the East India Company decided that Baji Rao’s pension and honours would die with him and would not be passed on to any successors. Nana Sahib lobbied hard sending an envoy, Azimullah Khan, to London to petition the Queen directly but to no avail.

This dispossessed Hindu aristocrat would play a dangerous double game before deciding who to support in the mutiny.

A Portrait of Nana Sahib, one of Victorian Britain’s most famous villains. – The Illustrated Times, 1857.

With the patronage of the Mughal Empire in New Deli the mutineers ransacked towns and cities. The Mughal Empire was to be reestablished of Hindus and Muslims, these combined forces where to evict the Christians from India forever. This turned a localised army mutiny into a more significant political challenge to the rule of the East India Company.

The slow response by the commander of the East India Company General Anson did not help. He underestimated the size and escalation of the challenge to the company’s authority. He would not be the only one to make that mistake in 1857

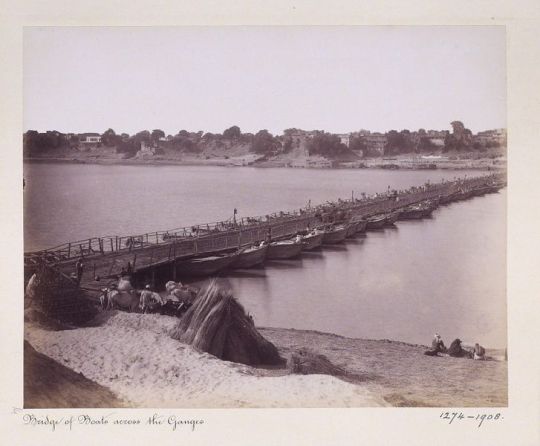

Bridge of boats across the Ganges at Cawnpore – Seeta Ram, 1814/15 – British Library

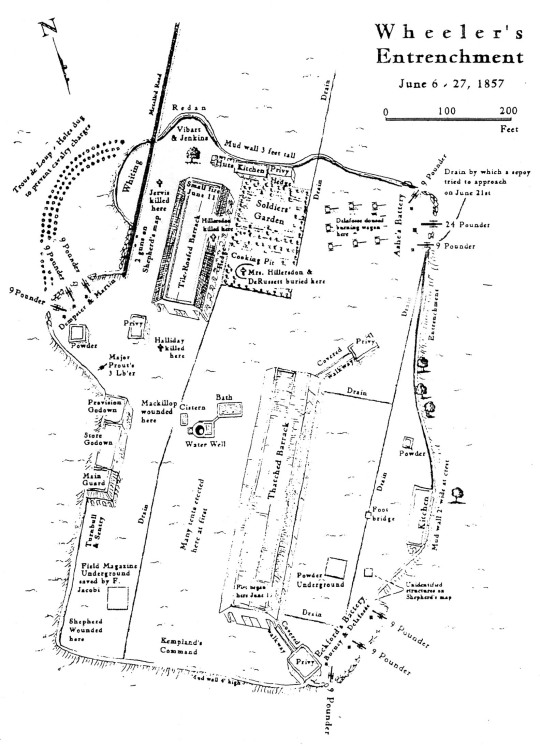

Wheeler expected reinforcements to come from the South of Cawnpore, so he made camp of defence a few miles South of the city at a small military base where barracks were being constructed. His hope was to build an entrenchment around this camp as a defence from the outside. However it was the height of the Indian hot season and digging defences was hampered by an iron backed ground. It was almost impossible to get the trenches below waist height and the surrounding area outside of the fortifications had buildings to shelter the enemy and their gunfire.

The biggest problem was the lack of decent sanitatary facilities. There was only one water well and that would be exposed to enemy fire.

The entrenchment would be fine to defend with a significant force of soldiers or for a very short period of time. As it was, there would be a thousand plus civilians with a pitifully small garrison of European soldiers who would end up having to defend for far longer than they had possibly anticipated.

Although no direct threat had yet occurred in Cawnpore, European families began to drift into the entrenchment and tried to find a space in one of the sturdier buildings available. The very sight of the Europeans withdrawing into relative safety was not unnoticed by the Indian sepoys and sowars.

To try and disperse the number of Indian soldiers away from Cawnpore, General Wheeler decided to send troops on various ‘missions’ to relieve garrisons in the region. They mutinied against the British, killing both their commanders. Oblivious to this the men making Entrenchment fortifications at the south of Cawnpore kept working.

Nana Sahib had declared his loyalty to the British and sent what volunteers he could spare to be at the disposal of Wheeler and for the defence of Cawnpore. He sent his units to camp just south of the Entrenchment, to guard the treasury. Wheeler had barely 250 forces in total and he had to defend a thousand odd civilians.

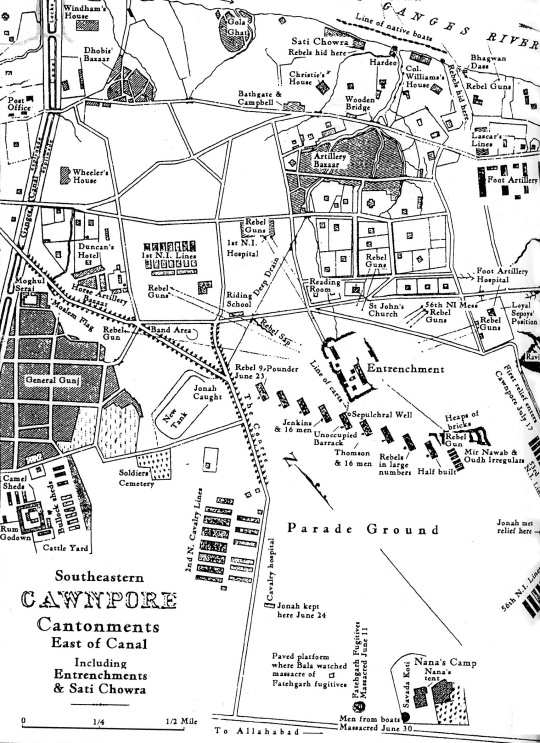

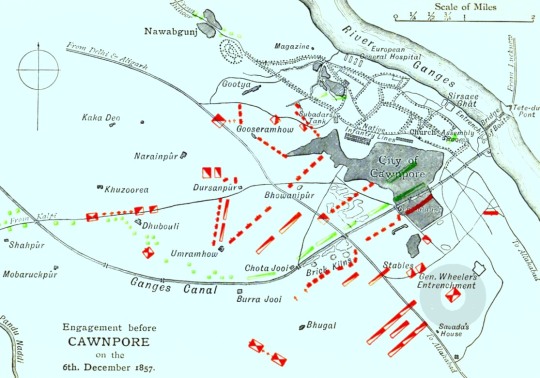

A Map of Cawnpore. The Entrenchment being centre-right.

Tensions would be raised on the night of June 2nd when a drunk Lieutenant Cox fired on his own guard. He missed, was disarmed and thrown into jail for the night. The following day the sowars were less than impressed when a hastily convened court failed to convict him of firing on his own troops. This seemed to confirm that there was one rule for the English and another for the Indians.

Rumours of mutiny and impending treachery were becoming so widespread that it was difficult to tell the truth from the rumours. There were still Native regiments based in the city. (The 1st, 53rd and 56th Native Infantry and the 2nd Bengal Cavalry).

It was to be the 2nd Bengal Cavalry that were the prime instigators of the mutiny. It seemed to them as if the English were already prepared for them to mutiny. They cited the insulting fortification of the entrenchment, artillery guns being primed and aimed at them, the fact that they had to collect their pay out of uniform and one by one so as to not all turn up in the entrenchment armed and en masse, the acquittal of Lt Cox and rumours that they were to be summonsed to a parade where they were to be blown to pieces all convinced the sowars that something was seriously amiss.

A map of Wheeler’s Entrenchment.

In the city at 1:30am on June 5th, three pistol shots signalled the start of the mutiny. At least one Rissaldar-Major Bhowani Singh refused to join his comrades and was cut down there and then.

As predicted by Wheeler the sowars began to burn buildings, loot and cause mayhem. The 53rd and 56th were groggily awoken by the panic and started to form up. The 56th began to panic and started to run off. European artillery opened up on the fleeing sepoys assuming they were mutineers too. If they hadn’t been before, they were now. Worse than that, the 53rd, Wheelers old regiment, were caught up in the cross fire. The confusion and panic had led the British defenders to fire upon what was probably the most loyal unit in the area. Soon virtually the entire native contingent had risen up or run off.

It was then that Nana Sahib’s and his men looted the treasury and set off down the Grand Trunk Road. He caught up with the bulk of the mutineers at Kalyanpur. Seeing advantage for himself, he therefore pleaded with the mutineers to about-turn and come back with him to besiege and capture the city on behalf of the Mughal Emperor, bribing the men with the British Gold.

Ominously for the British, the mutineers trundled back into town. This time, they made sure that they had expunged all the Europeans from outside of the entrenchment and systematically plundered and destroyed all European owned property. Native Christians were also singled out for gruesome fates.

Whilst all this was happening Nana Sahib took the time to write a letter to General Wheeler informing him to expect an attack the next morning at 10am!

A larger map of Cawnpore showing the Entrenchment bottom left and the Grand Trunk Road slashing top left to bottom right.

The attack started half an hour late at 10:30 on June 6th. It would actually take the form of a prolonged artillery bombardment but this offered little comfort to the defenders who realised quickly that the mutineers had more and better guns available to them and that the entrenchment offered and that they were surrounded.

Fortunately for the British, the mutineers were reluctant to test the defences in an all out assault. In fact, they had been led to believe (falsely) that the entrenchment had gunpowder filled trenches.

The following days, and indeed weeks, would only confirm what a difficult position this was to defend. The fact that it was the hottest time of the year only added to the miseries of the defenders. The one well was exposed to the enemy artillerymen and snipers who took delight in aiming at the desperately thirsty defenders. Water extraction would have to take place at night to stand any chance of success. A second dried-up well would have to serve as the make-shift burial chamber. The solid ground was too difficult to dig individual graves. Dead bodies would have to be piled up outside the buildings awaiting nightfall when they would be dragged and dumped with as much ceremony as could be summonsed given the circumstances.

The defenders were becoming increasingly desperate, their already small quantity of soldiers was being steadily whittled down by the combined attritional effects of successive bombardments, snipers, assaults, disease and poor to non-existent medical supplies. Food and water were dangerously low and the hot season was still beating down the sun unmercifully on the defenders. By the 21st of June, they had probably lost a third of their number.

With the prospect of relief seemingly as far away as ever, General Wheeler assented to Jonah Shepherd slipping out of the entrenchment in disguise to ascertain the condition of the mutineer army. Jonah was picked up pretty quickly by the mutineers although they failed to appreciate that he had been part of the defending force and merely imprisoned him as a wastrel.

Whilst this was all taking place, Nana Sahib and his advisers had come up with a plan of their own to end the deadlock. They used a female European prisoner, Rose Greenway, to approach the entrenchment with the idea of initiating negotiations. She conveyed to the defenders a note that said that Nana Sahib was willing to offer safe passage to Allahabad for all those who lay down their arms. This offer was rejected by General Wheeler ostensibly because it hadn’t been signed and that therefore no personal guarantee had been offered.

The following day, June 25th, a second note was brought, this time by a different female prisoner, a Mrs Jacobi. This letter was signed by Nana Sahib himself. Debate swirled amongst the survivors and it was clear that there were two camps forming: Those determined to hold out versus those wishing to lay their trust in Nana Sahib’s assurance. Wheeler, already in a poor state of mind, was actually in favour of holding out, but when some of his officers began to talk of the sense in escorting the surviving women and children to safety, the old general relented and offered to lay down his arms in return for safe passage.

The next 24 hours saw an immediate improvement in the condition of the defenders. No longer having to brave the bombardment just to get a bucket of water meant that the defenders could drink their fill and wash and bathe for the first time in three weeks. Additionally, as the remaining rations would no longer be required for a long siege, allowances were doubled and the defenders could eat satisfying quantities for the first time in a long time.

With a day for preparation and laying to rest any remaining fallen comrades, the morning of the 27th June was designated as the day to board the boats to take them down the Ganges to Allahabad.

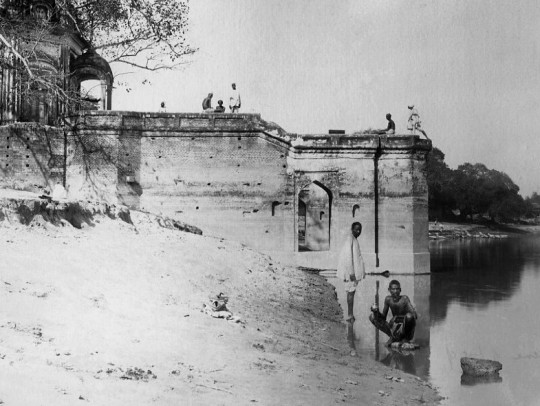

The ‘Sati Chaura Ghat’ on the bank of the River Ganges.

A large column was formed with General Wheeler leading from the front. They tried to show as much dignity as they could muster but the privations and conditions were unable to be concealed from the Indian onlookers. The respect shown to the front of the column gradually broke down as looters and pilferers tried their luck in grabbing the personal effects of those further down the column. More locals swarmed into the entrenchment hoping to find things of value left behind by the defenders.

One unanticipated problem was that the river was unusually dry and the boats were left fairly high and dry. It would take some serious dragging and effort to find the deeper parts of the Ganges. General Wheeler and his party, being the first to arrive, were the first aboard and the first to manage to set their boat adrift. It was at this point that some of the mutineers began to look nervously at the general’s boat floating downstream. It was clear that not all the boats were yet loaded and there were still a lot of Europeans waiting to board the at all.

There was a bit of confusion as the Indian boatmen jumped overboard and made for the banks. They knocked over the cooking fires on the boats before jumping in, thus setting some of the boats ablaze. Then, all hell broke loose. Tatya Tope ordered the 2nd Bengal Cavalry unit and some artillery pieces to open fire on the hapless Europeans. The massacre was merciless. Bullets flew from all directions as the Europeans desperately attempted to scramble into the burning boats.

Women and children were inevitably caught up in the deadly fire. At the boarding point, the carnage continued. It then stopped almost as suddenly as it started when the mutineers suddenly ceased fire. Any remaining women and children were taken prisoner and escorted to Savada House. Any remaining men were cut down where they stood. Approximately 120 women and children were thus taken away.

Wheeler’s boat, floating away was pursued. Under-fire and with the low tide, the sandbanks and rocks hampered escape efforts. General Wheeler’s own family members were probably killed in the water trying to free the boat.

Lieutenant Thomson led a last gasp desperate charge out of the river into the mutineers. Unbelievably, the suicidal charge worked and in fact allowed them to capture some vital ammunition. The next morning yet another grounding resulted in another charge by Thomson and 11 volunteers. Having left the boat the mutineers captured it and the people on-board were unceremoniously escorted off the boat. The men where executed on the bank and the women and children were taken back to Savada house. The men in Thomsons charge ran, hid, attacked and were surrounded. They ran to the river, four survived including Thomson – they swam to the centre of the river. They drifted downstream as best they could – although they now had to worry about crocodiles too. They came exhaustively ashore a few hours later. Their fortunes finally turned for the better when they were discovered by Rajput matchlockmen who worked for the Raja Dirigibijah Singh who had remained loyal to the British. They were taken, or rather carried, to the Raja’s palace. With the exception of Jonah Shepherd, these were the only male survivors of the ordeal.

A photograph of the river in 1908 showing the width at a fuller tide.

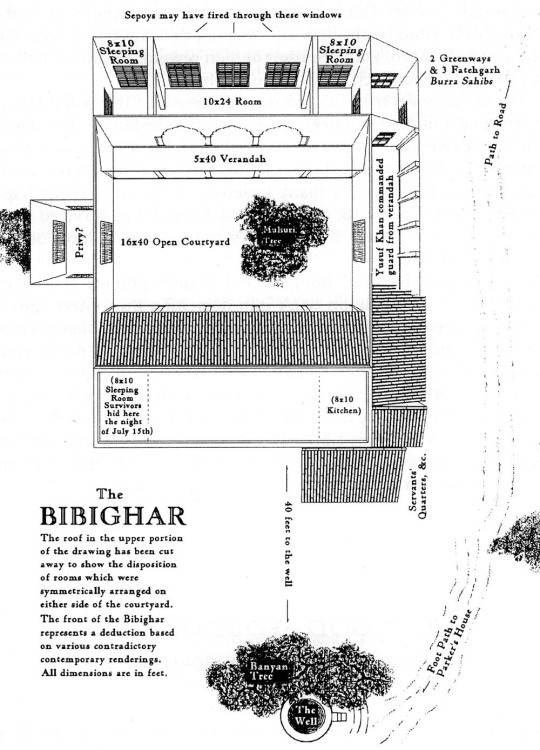

The dazed, shocked and confused women and children were moved from Savada House to the Bibighar. It was terribly cramped for the women and children. The original 120 women and children would later be joined by other women and children from Wheeler’s boat, some from a second flotilla from escaping violence in Fatehgarh. In total there were about 200 souls crammed into the house.

Nana Sahib placed the care for these survivors under one of his mistresses serving girls who would become known as the Begum. Her real name was Hussaini Khanum. She seemed particularly unmoved by the plight of her captives and did little to help them. Food was provided but little thought was given to the dignity or care of the prisoners.

Nana Sahib had decided to use these prisoners as bargaining chips to try and keep back the relieving force of Havelock and Neill. They demanded that the British retreat to Allahabad. Havelock’s force though advanced relentlessly towards Cawnpore. An army was sent by Nana Sahib to intercept the relatively small but determined flying column. They met at Fatehpur on July 12th where Havelock’s forces quickly out-manoeuvred the larger mutineer force and captured the town.

As it became clear that the British were going to enter Cawnpore, Nana Sahib, Tatya Tope and Azimullah Khan debated about what to do with their captives. As mutineers scurried out of the city, it was not clear how 200 women and children could be escorted anywhere and their use as bargaining chips had patently failed. Azimullah Khan was also worried that Nana Sahib might flee and abandon the mutiny altogether. The order was given to eliminate their prisoners.

At first the guarding Sepoys refused to obey the order. They had executed the remaining men without much thought, but murdering women and children was another matter. It was only when Tatya Tope threatened to have the sepoys themselves executed for dereliction of duty that they agree to try and remove the women and children from the courtyard for their execution.

The women had already realised what was going on with the execution of the remaining menfolk. They barricaded themselves in as best they could by tying the door handles with clothing. Some twenty soldiers opened fire into the cramped compound. A second squad that was to fire the second volley was so disturbed by what they saw that they discharged their shots into the air and staggered away. The sepoys now adamantly refused to finish the job off.

The Begum was so irate at what she called the cowardice of the sepoys that she had to get recruit her lover Sarvur Khan to finish the job off. He went into town and hired butchers with cleavers to finish off the nasty business. They were hacked to death. The following day, orders were given by Nana Sahib to clean up the scene of the massacre. They were surprised to come across the half dozen or so women and children who were still alive. The women actually threw themselves down the well rather than be murdered on the spot. The children, who were only five and six years of age, tried to evade the scavengers and mutineers until exhausted. They were then chased around the corner into waiting executioners who decapitated them. Eventually, all the bodies were looted of whatever pitiful possessions that they still had on their bodies and were then dragged to the nearby well and thrown down it.

The horror was indescribable. There was so much blood that they could not clean the walls and floors despite their attempts at scrubbing.

On the 16th of July, a group of British officers and soldiers were directed by fearful local Indians to the Bibighar. They were horrified by the smell and sight that greeted them. They had assumed that they were arriving to rescue the women and children. Any feelings of elation at the victories and relief quickly turned to feelings of despair and then through to vengeance.

A plan of the Bibighar, where the slaughter took place.

It was beyond comprehension for Victorian soldiers to believe that innocent women and children could be butchered in such a manner. Most pitiful were the tiny hand and footprints of the children who had been slaughtered.

A photo of the well from 1858.

Discipline had all but collapsed amongst the British who were in utter despair at the massacre. The slaughterhouse Bibighar became a place of pilgrimage for the British soldiers who then turned their indignation on any local Indians who happened to be in the way. They wondered how any of the locals could have let this massacre occur and do nothing to intervene and stop it. Neutrals became hostiles in the minds of the British soldiers. Looting, burning of houses and murder became acceptable as old testament-style vengeance was meted out indiscriminately. Looted alcohol fuelled the despair and destruction.

The worst vengeance was applied to any mutineer captured. No mercy was shown to them at all. A set of nooses was set up next to the well at the Bibighar, so that they could die within sight of the massacre. Colonel Neill decided that the crime was so serious, that all captured mutineers would be expected to clean up the scene of the massacre literally with their tongues. They were beaten and clubbed into licking the floor of the Bibighar compound. They would then be forced to eat Beef if Hindu or Pork if Muslim and then hanged at the gallows adjacent. Sweepers were employed to execute high-caste Brahmins. Some Muslims were sown into pig skins before being hung. The idea was to ritually humiliate and defile the victims to preclude any reward they might have expected to find in the afterlife.

The memorial at Cawnpore, 1860

Memorial at Cawnpore (present-day Kanpur), devised by Charlotte, Countess Canning (1817-61) and her sister Marchioness of Waterford (1818-91), with the figure of an angel executed by Baron Carlo Marochetti (1805-67) and a screen by Colonel Sir Henry Yule (1820-89). C. B. Thornhill, Commissioner of Allahabad and superintending architect.

Count and Countess Canning paid for the sculpture, the large park surrounding it was paid for by a levy on the citizens of Cawnpore, as a sort of punishment.

Regardless of the savage history of the tapestry, I requested it as a Christmas gift. My mother and the antique dealer then both acted in a masquerade of it being sold until I was delighted on Christmas day with it. The detail of it is amazing. The work of the windows and brickwork, not to say the angel. All hand stitched.

† The History of the Indian Mutiny Giving a Detailed Account of the Sepoy Insurrection in India and a Concise History of the Great Military Events Which Have Tended to Consolidate British Empire in Hindostan – The London Printing and Publishing Company, London, 1858

The Body of text for this post and the maps were sourced from this website:

http://www.britishempire.co.uk/forces/armycampaigns/indiancampaigns/mutiny/cawnpore.htm