When I married Salvador Dali his moustache was. no bigger than a thread of silk,’ his wife Gala explains. ‘We lived in a one-roomed fisherman’s hut overlooking Port Lligat in Spain, and while I learned to fish and prepare lobsters à l’espagnole,

Dali struggled with surrealist paintings. Every six months both of them went to Paris and tried to sell his work. Today he places commissions on a three-year waiting list, and intimidates the world with a moustache capable of anything from a heavily waxed coil to a vertical sword thrust. ‘Sometimes,’ Mrs. Dali admits, ‘I worry in case he scratches his eyes out.’

The fisherman’s hut, too, has grown. ‘Our Hamlet’ is the way Mr. Dali describes it. Apart from three cottages and a rather new-looking hotel, Port Lligat is the Dali home. One by one, neighbouring cottages and outhouses have been given an extra storey, whitewashed, and added to the home structure. The result is a nest of twelve different roof levels set between terraced hills, with a tiny bay and four rowing boats just six steps down from the front door.

‘I still go fishing.’ says Mrs. Dali, ‘but the boats are fitted with motors now, and I no longer have to prepare the meal afterwards.’

She trained a staff of three–manservant-cum-chauffeur, chambermaid, and cook-to run the ten-roamed house so that she could deal with her own work as secretary, artist‘s model (she is the dark-haired beauty in most of his paintings), and keeper of the Great Privacy. ‘I arrange for us to have no telephone and no guest room,‘ she says with obvious satisfaction. ‘Visitors either come by yacht and sleep on board; or they take our mountain road, which is not good, and sleep at the hotel.’

In fact, the last stretch of road is so bad that the Dali Cadillac has to have a house and garden of its own in nearby Cadaques. ‘We complete our journey by local taxi, which is like riding a mountain goat.’

‘Cosmic inspiration’

In spite of their inaccessibility and a wish to safeguard privacy, the Dalis are not inhospitable, and friends are always welcome-after eight o’clock in the evening. ‘For six months of the year we live in American hotels,’ Salvador Dali explains. ‘I make big appearance for public and friends. I design nightclubs, create fantastic Dali parties. Port Lligat is secret place, where I was little boy, where I work always. I bring strong cosmic forces back from America, Gala brings canvas and brushes, and I paint in studio.’

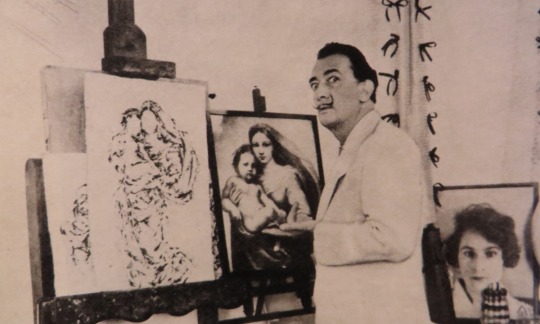

He is now working on the Greatest Dali Masterpiece, a religious canvas over twelve feet high and nine feet wide. By using pulleys and a slot in the studio floor which opens on to cellars below, he is able to adjust the canvas to any working height or whisk it out of sight altogether. He hopes he can complete the work within six months. He then has fifteen commissioned portraits to paint-at an average fee of £7,000 for each one. ‘Money itself does not interest,’ he says. ‘Only the symbol is very strong in me.’

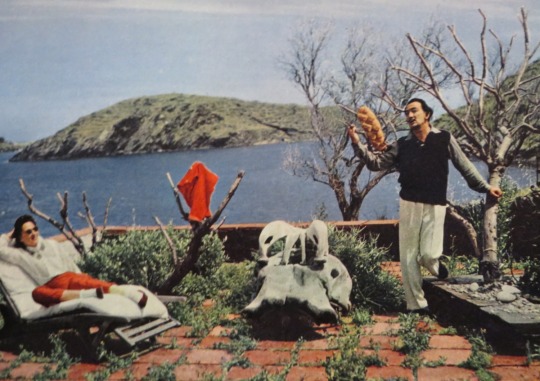

The studio, like the bedroom and the main sitting room, has a sloping, heavily beamed ceiling, and everything is distempered white. No artistic mess or muddle here, only a deliberate and persistent study in contrast. A life-size Apollo, for example, sporting a Davy Crockett hat ‘to keep the mind sparking’; a jewelled casket balanced on a tripod of French loaves.

‘Bread is obsession,’ he explains. ‘It captures many shapes for me. Like sea urchin which has cosmic inspiration, and rhinoceros for strong fear. I learn secret and use in my work.’

He has just completed a film (to be shown at the next Cannes Festival) which tells the story of his strange philosophy. It took him two years to make and he calls it The Prodigious History of the Rhinoceros and the Lawmaker.

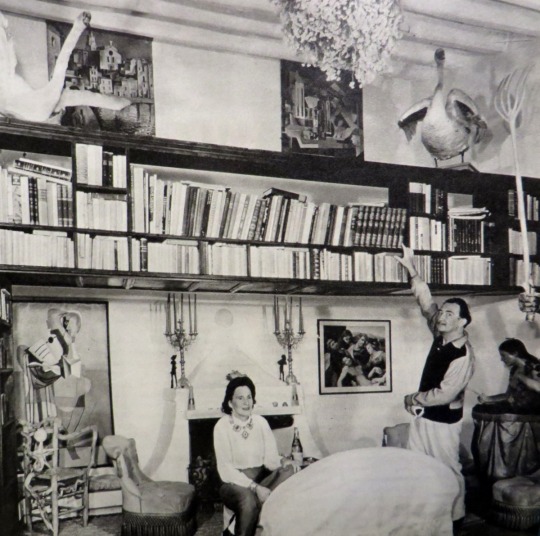

These obsessions also play a decorative and oddly formal part in the home. Each room holds at least one secret. The main lounge, predominantly white with yellow upholstery and a floor of polished bricks, has two stuffed swans perched on the ‘canopy’ of books which divides the room; the entrance hall is furnished with a life-size bear wearing elaborate chains of office, and a couch inspired by the line of Mae West’s lips.

The bookcase has two stuffed swans looking down on the room.

The rooms themselves vary in size and shape, and they are all built on different levels. Most impressive is the hundred and-fourteen feet long, three-tiered bedroom, consisting of lower Sitting room with yellow pin-cushion settees, curio landing seven stairs up, decorated with elaborate jars of sugared almonds, and the bedroom proper seven steps above that. This has a red and blue canopy for the two divans, and a large fireplace with a walled-in sitting recess inspired by one of Dali’s sketches.

All the fireplaces at Port Lligat are based on designs by Salvador Dali, but Gala is the one who chooses the furniture and decides on the decor. Her approach is simple and effective. ‘A house must be warm,’ she says, ‘it must also be nourishing for the mind.’ She guards against the strong mountain wind (Lligat is on the East Coast some forty miles south of the French border) with central heating. She keeps the house ‘alive’ with hundreds of well-thumbed books, and a retinue of comfortable animals: she has white canaries in her bedroom, cats downstairs, and pigeons in a vast pagoda-style dovecote outside.

Although she is Russian by birth and international by upbringing, Mrs. Dali’s choice of furniture is mainly local. For the dining room she has fifteenth-century refectory~style pieces from a nearby monastery; she bought, and dismantled, a vintage black and gold Catalan bedstead to make headboards for the divans.

‘Silk and brocade is right for town,’ she says. ‘Here we need crisp white linen curtains. On the floor I have rush matting used for covering the local ox wagons.’ A samovar is her one concession to the past, but even this comes in useful on chilly evenings.

By mutual consent, Time, in the shape of a mad rococo clock, is firmly relegated to a decorative comer of the rock garden outside. They nevertheless follow a routine of work, breakfast, work-swim, work-siesta, and work which is governed in detail by the light, and Salvador Dali himself-self-acclaimed genius. ‘I am. fifty three,’ he says, ‘but even as a boy I paint With originality. Two times they expel me from college,

I am so good.’ He had a tempestuous school career at Figueras, twenty miles from Lligat, and his parents weathered his ‘Stone Period‘ with desperate patience. ‘I painted stones and tied them to‘ canvas,’ he says. Unfortunately, they were rarely secure, and his father would explain the noise to startled visitors: ‘It‘s nothing, just another stone that’s dropped from our child’s sky.’ Later he went to art school in Madrid, and on to Paris where he found the centre of surrealism and a fascinating but meagre living.

Pagoda-style dovecote decorated with pitchfork perches – is home to a hundred pigeons, and also an extension to the Dali game larder.

During one of his many return visits to Spain, he met Gala on holiday, courted her in French, and proposed with ninety red roses which he could ill afford. Encouraged by his wife, he clinched his reputation in Paris with some of his most brilliant work. and in 1935 decided to take a one-man show to America. The Dalis arrived in New York with thirty pieces of luggage, and the world’s biggest loaf for dramatic effect.

The loaf was ignored, but the paintings, were a fabulous success, particularly his portrait of Gala balancing a pair of chops on her shoulders. Questioned about significance, he replied: ‘I like Gala, also chops.’

At home he has always been quietly spoken and unexpectedly modest. Dark-haired and dark-skinned, he is an expert showman who delights in dressing up. He has an extensive ‘Spanish’ wardrobe, although most of his fancy Catalan shirts are in fact cowboy ones, bought from drugstores in America, and modified at home. ‘

“During the day I wear knee-length trousers; in the evening I always have them full length. She has dozens of pairs, mostly skin tight and all couturier-made.

The Dalis have one luxury bathroom with an excellent supply of hot and cold rain water, but mineral water is Gala’s great personal extravagance. ‘We buy it in bottles for cooking, but I use it for washing as well.’

The menu at Port Lligat is governed by Mr. Dali’s standards, ‘Food must have well-defined shape, so intelligence can grasp it,’ he says. ‘Shell fish and chop is good. Spinach bad.’ A weekly delivery of food supplies from Figueras is augmented by local fish, rabbits, and the famous Dali pigeons.

The kitchen, decorated with exhibition posters and presentation plaques, has an electric ’fridge (run off their own power plant) and an Open range for cooking, because the staff prefers to use charcoal. Life with Salvador is remote from local custom, but he does create fiestas of his own. He will organize a firework display for the fishermen and their children to celebrate the completion of a new work.

The bear in the hallway holds a lamp-stand and a basket for gloves.

He recently bought a barn in Cadaques which he plans to convert into a private cinema for Chaplin films and Dali premieres. He spends most of his evenings writing at home (he is working on his third book), but occasionally the local choir is invited for ‘champagne and songs’. In return, they bring gifts of fragrant herbs for the house. ‘They love Dali,’ his wife comments, ‘and understand him a little.’ Certainly they would have appreciated the way Freud described him after their one and only meeting: ‘I have never seen a more complete example of a Spaniard. What a fanatic!’