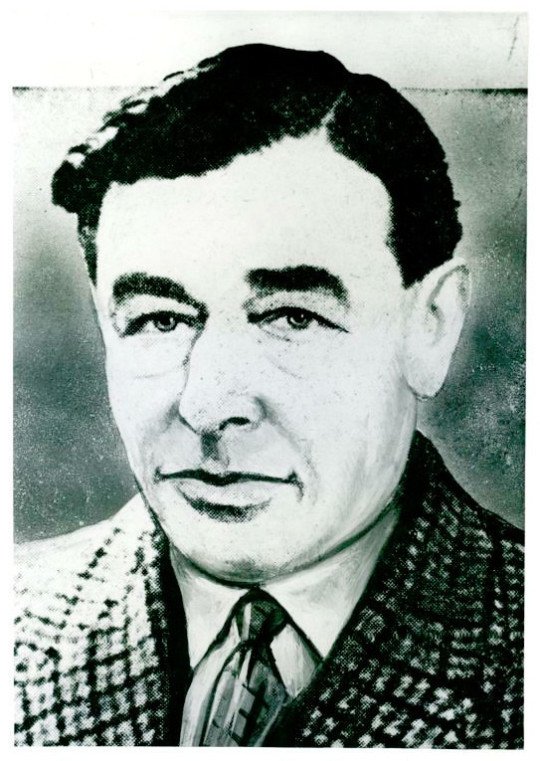

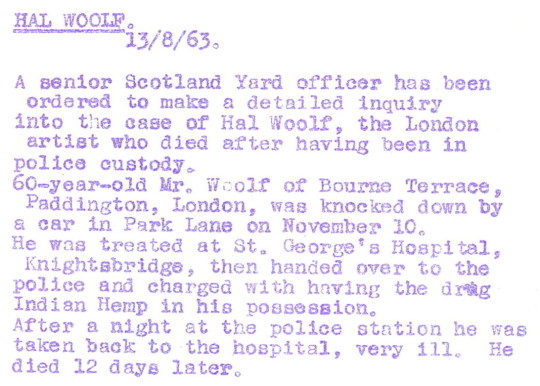

Herman ‘Hal’ Woolf (1902-1962) studied art at Chelsea Polytechnic and later in Paris at La Grande Chaumiere. He had exhibited with the Royal Academy, become a member of the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Royal Society of Portrait Painters, and was a member of the London Group, and with the National Society of Painters and Gravers. He designed posters, and twelve days after being hit by a car in Park Lane on November 10 1962, he was found dead in police custody.

Hal Woolf’s case became part of the Skelhorn Report. The case is reported in Hansard, part of a inquiry in the House of Commons.

Mr. Herman Woolf was knocked down by a car in Central London in November, 1962. He was taken to hospital and X-rayed there. A short time afterwards he was considered fit for discharge, and he was promptly arrested by the police on the allegation that he was in possession of a dangerous drug. Within 24 hours he was returned to that very same hospital, gravely ill and injured, in a comatose condition. Shortly after that he was transferred to another hospital, and 12 days later he was dead.

During this whole time—from 10th to 23rd November, 1962—the late Mr. Woolf was under police surveillance, and most of the time under police arrest. In spite of the fact that some days after this unfortunate incident and his transfer to a hospital in the suburbs more than one of his friends reported him missing at a London police station, his former wife—who was his next-of-kin—and his friends were not notified by the police of his whereabouts until after he had died.

The drug found on him was Indian Hemp, a type of Cannabis. Having had a lot of success he seems to be mostly forgotten about today. His memorial show was held at the Woodstock Gallery, London.

Hal Woolf – Salcombe – Shell Poster, 1931

One of the troubles about the whole of this tragedy in 1963 was that those equipped with authority to deal with this matter in any way did not show themselves to be over-anxious to investigate the circumstances of the case. At the inquest Mrs. Woolf objected to the haste with which it was being held, and asked to be represented, but her objection was brushed aside. Later, her legal advisers had great difficulty in getting a transcript of the evidence—such as it was—which had been given at the inquest.

Last summer when, as a result of an article in the magazine Private Eye, the national Press took up the Woolf case, and suspicions and anxieties were aroused among many people about it, an investigation was held by Scotland Yard, under Detective Superintendent Axon. It took a very short time. I know none of the details. There was a report to the Commissioner, and comfortable and complacent conclusions were issued to the Press. But the report has never been published. Neither the public nor Members of Parliament know any of its details.

Woolf Enquiry – HC Deb 15 May 1964 vol 695 cc837-53

Despite the tragic and curious end to his life Hal Woolf has a remarkable legacy in British art and it is a shame he isn’t better known. I always think an artist who Jack Beddington employed was a good bench mark.

My right hon. Friend is convinced—and I hope that the House will take this assurance in a cooperative spirit—that no useful purpose would be served in publishing the proceedings of this inquiry and that it would, in terms of the undertaking he gave in the beginning, be quite wrong to do so.