from The Guardian, May 7th 2007.

A woman of great beauty and personal magnetism, Angelica Garnett, who has died aged 93, had many gifts. She turned her hand to mosaics, painting and sculpture and transformed domestic interiors with hand-painted decorations. As a writer, she used words with great sensitivity and precision. Her speaking voice was startlingly beautiful owing to her exquisite pronunciation. Her creativity must have been partly genetic, for she was the daughter of the artists Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, a parentage that gave her a double share of Bloomsbury inheritance.

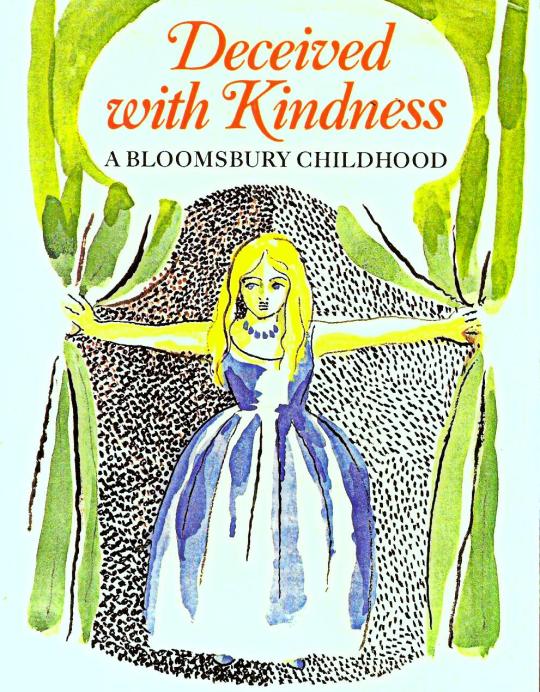

This proved to be both a blessing and a burden. During much of her life, and particularly in the essays and books that she wrote, she struggled to come to terms with the psychological complexities that she associated with her upbringing. Her difficulties and anger with her elders emerged in her memoir Deceived With Kindness (1984), which contributed a poignant coda to the history of Bloomsbury and triggered a fresh spate of antagonism towards it.

To some extent, Angelica shared this negative view, while, at the same time, remaining a principal exponent of Bloomsbury, its values and way of life. Listening to her speak in public about herself and Bloomsbury, it was distressing to witness the tension between her pride in her forebears and the pain that these memories caused.

Her mother often reminded Angelica that she had French blood in her veins, for her great-great-grandmother had been married to the Chevalier de l’Etang, a member of Marie Antoinette’s household. But it hardly needed this distant connection to stimulate the young girl’s interest in all things French, including art. In her childhood, there were long periods spent in the south, mostly in a small villa outside Cassis.

When she was 18, she was sent to live for a while with a family in Paris so that she could learn the language. In old age she observed that her life had been “loosely and pervasively mixed up with France for as long as I can remember” and that “nothing in it would be the same or have the same flavour without this connection”. The country eventually became her permanent home and her last 30 years were spent living in Forcalquier.

She had been born at Charleston, a Sussex farmhouse situated at the foot of the South Downs and at some remove from the nearby village of Firle. Nowadays visitors stream through the house, during the six months of the year that it is open to the public, but at the time of Angelica’s birth it was remote from civilisation and devoid of modern comforts. Vanessa Bell had rented it so that Grant and his friend David Garnett, both conscientious objectors, could obtain necessary employment as farm labourers. Her husband Clive Bell visited at weekends, but marital relations between them had ceased and Vanessa had fallen in love with Grant. He returned her love, despite the fact that he was predominantly homosexual.

Knowing this, Vanessa agreed that the good-looking Garnett, with whom Grant became obsessed around 1914, could become part of their wartime menage. Soon after Angelica was born, she was weighed in a shoebox on the kitchen scales. Garnett, watching the procedure, was astonished that the baby already showed signs of intelligence and independent will. He wrote presciently to Lytton Strachey: “Its beauty is the remarkable thing … I think of marrying it; when she is 20 I shall be 46 — will it be scandalous?” Angelica did indeed marry into her parents’ generation and Garnett was to be her husband.

The immediate issue at the time of her birth was her paternity. This was attributed to Clive, partly to protect the servants at Charleston from embarrassing gossip, and possibly also for financial reasons, as it was the habit of Clive’s colliery-owning father to settle allowances on his grandchildren. From what Vanessa later told Angelica, she also felt that Grant was too young to become a father (though he was by then 33). As a result, Angelica grew up believing she had the same father as her two brothers, Julian and Quentin, and that Grant was no more than an enchanting family friend. By the standards of the day, Bloomsbury was highly unconventional.

Angelica’s early life was spent in an unorthodox and slightly precious environment. As Vanessa’s youngest child and only daughter, she lived under a spotlight of concentrated attention. (She later fictionalised this experience in her short story When All the Leaves Were Green: “It was like being in a hall of mirrors, where she saw only reflections of herself.”) Her mother readily gave in to her whims.

At the age of 10 she was sent as a boarder to Langford Grove, in Essex. Its headteacher cared more for culture than the curriculum and thought nothing of interrupting the timetable in order to carry off select pupils to a London play reviewed in the newspaper that morning, or to attend a concert in Cambridge. More educative for Angelica would have been the Bloomsbury conversations at home, or over tea with her uncle and aunt Leonard and Virginia Woolf. Often Angelica went to see Virginia alone with Vanessa, and amused herself while they gossiped, ever afterwards envying the intimate relations between sisters.

In the summer of 1937, when Angelica was 18, Vanessa informed her of her true parentage. This information did not alter things greatly. Angelica was advised by Vanessa not to tell Clive, as he liked to think of her as his daughter, and for some reason she did not approach Grant with her new knowledge.

He maintained a barrier of simplicity and kindness that prevented her seeing what lay behind it. Later she asked herself if in fact there was anything further to see. “Assuredly there was, but it was too nebulous, private and self-centred to respond to the demands of a daughter. As a result our relationship, though in many ways delightful, was a mere simulacrum. We were not like father and daughter. There were no fights or struggles, no displays of authority and no moments of increased love and affection. All was gentle, equable and superficial … My dream of the perfect father — unrealised — possessed me … My marriage was but a continuation of it.”

By the time she married Garnett — “Bunny”, as he was known to friends and family — he had become a renowned editor, reviewer and novelist. The marriage took place in 1942, two years after his first wife had died of cancer. Their preceding affair had caused bad relations between Bunny and Grant and Vanessa Bell, but with the marriage came an uneasy truce.

Angelica moved into Hilton Hall, Cambridgeshire, which Bunny had acquired in 1924. A Jacobean house that had been altered in the mid-18th century in a slightly old-fashioned countrified manner, it made an often cold but romantic, commodious setting in which to bring up their four daughters, Amaryllis, Henrietta and the twins Fanny and Nerissa, and to accommodate Bunny’s two sons by his first marriage. The house was a hotbed of creativity: not only were all four daughters highly talented, but Angelica, who had earlier studied acting under Michel Saint-Denis and painting at the Euston Road School, now had her own studio. She painted and Bunny wrote.

The marriage, however, as Angelica later remarked, had been an act of rebellion and was ill-judged. After some 25 years, they parted. For Angelica, there followed a nomadic period: she set up home in Islington, north London, then moved back to Charleston after Grant’s death in 1978, there experiencing severe depression. Next she bought a house nearby, at Ringmer, before finally settling down in Forcalquier. There were further relations with men who had been associated with Grant, but she never remarried. One of her most constant admirers was her brother Quentin and her likeness appears often in his paintings and ceramic figurines.

In her own work, she picked up sudden enthusiasms, some of which she equally quickly dropped. In the 1960s she worked for a period with mosaics, also publishing a manual on this medium in 1967. She was primarily a painter, but in the 1980s revealed a flair for constructed sculpture, making witty and concise use of found objects and materials. Exhibitions of her work were held in Milan, with Deborah Gage in London, at Forcalquier and elsewhere.