Category: Uncategorised

When doing art history one always get Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) projected into your face, likely because it’s designed to be interactive. However, the work of this era I have always favoured and that rather blew my seventeen year old mind was God (1917) by Morton Livingston Schamberg and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. It is an example of readymade art, a term coined by Marcel Duchamp in 1915 to describe his found objects. God is a 10½ inch high cast iron sink u-bend turned upside down and mounted on a wooden mitre box.

The year is 1913 and Elsa Endell, kaleidoscopic performance artist and poet is on her way to New York’s city hall for her third marriage, this time to a German Baron named Leopold von Freytag-Loringhoven. En route, Elsa spots a rusted iron ring. To Elsa this street trash was a totem of her marriage to be, and in an act marking a new era in the definition of ‘art’ — Elsa called this found object an artwork.

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven was not credited with the shattering of artistic tradition. A year later, Elsa’s close friend Marcel Duchamp would showcase Bottle Rack — a found object he claimed as a new category of art, the ‘readymade.’

Though founded in 2001, wikipedia wasn’t the internet’s first enciclopedia. The idea was really formed with the The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy book and the iPad looking Guide with ‘Don’t Panic’ in friendly letters over the cover. Douglas Adams wanted to use the internet somehow and when the rise of the dot.com boom in the late 1990s saw companies, artists and musicians all trying to cash in on the free promotion of the internet he thought about making guide a real thing. It launched in 1999.

The website was called h2g2, and like wikipedia, it was a collaborative online encyclopedia project. Users would write and edit the content. Early on there was a focus on travel, to ape the idea of the Hitchhikers Guide.., it would have independent reviews of towns and good places to see. The early version was called the ‘Earth edition’ of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Over time people found it more useful for an encyclopedia

It describes itself as “an unconventional guide to life, the universe, and everything”, in the spirit of the fictional publication The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy from the science fiction comedy series of the same name by Douglas Adams.

The website was funded by Adams himself. Originally to get the content going he employed a small staff to make basic listings as well as the coding to make the site possible. The software used was made in PERL for the site and called DNA (Douglas Neil Adams). It would be monitised by the software sales to other companies including the BBC. When the dot come bubble popped the BBC took over the running of the H2G2 website as they wanted a digital version of Teletext/CeeFax. They would use the DNA software until 2011 when the BBC had all their websites updated.

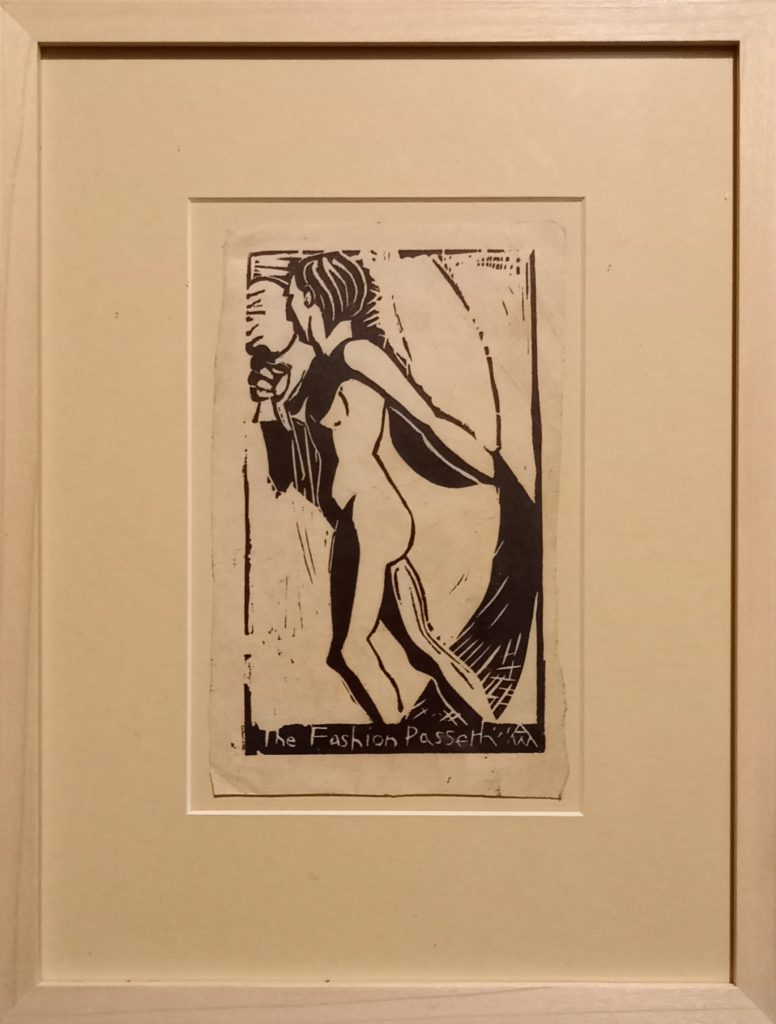

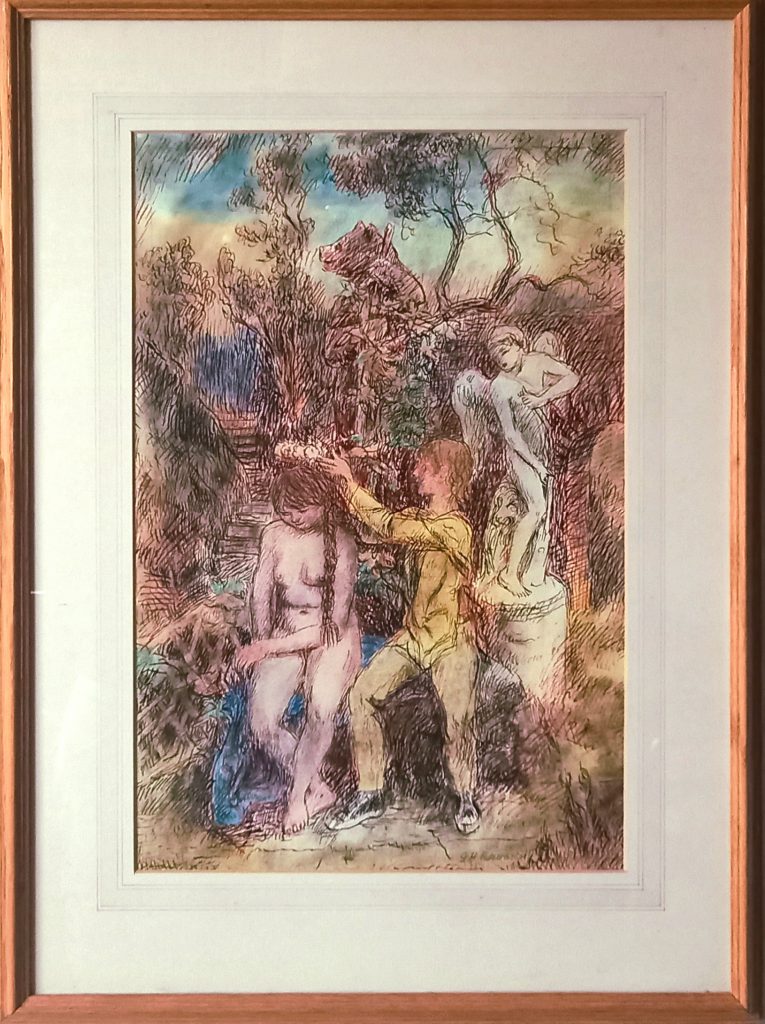

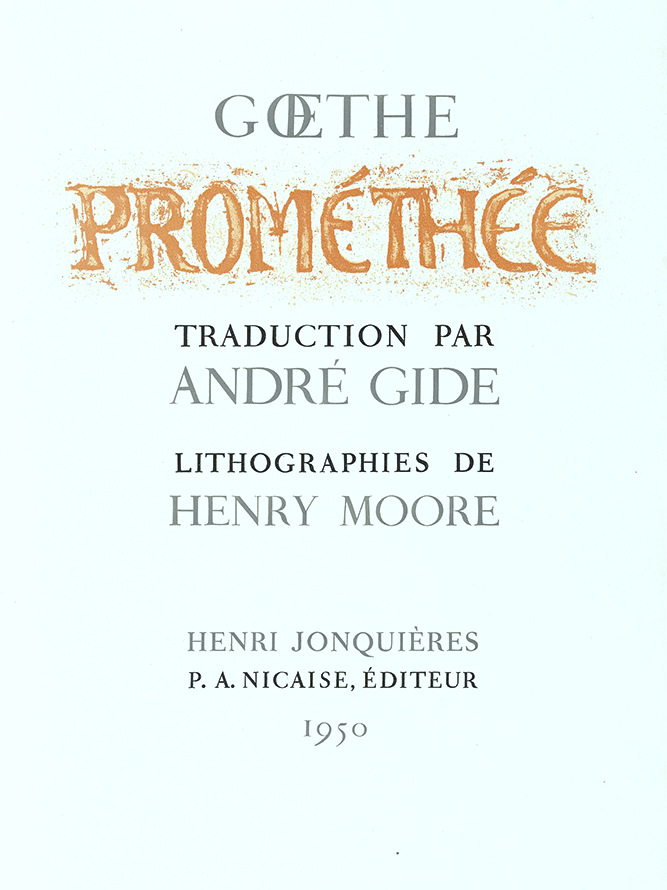

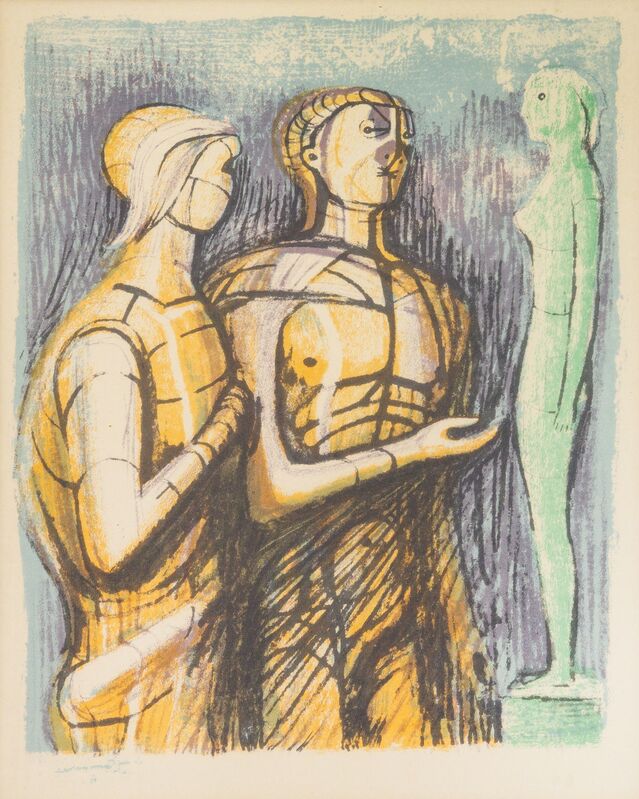

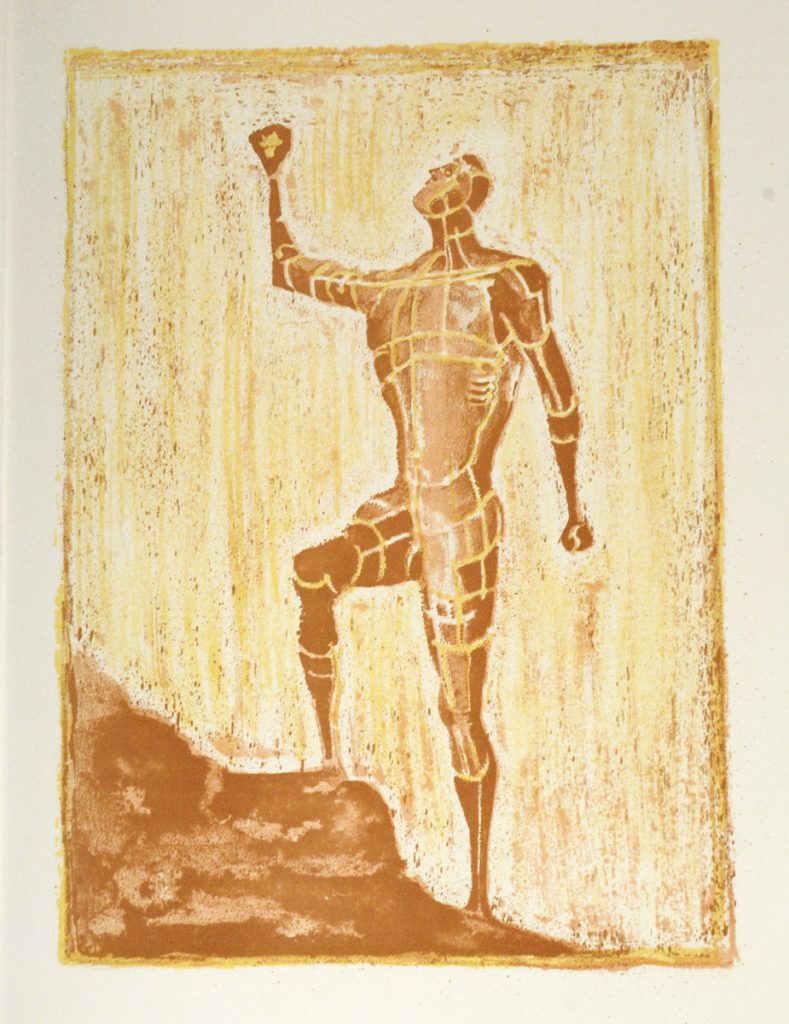

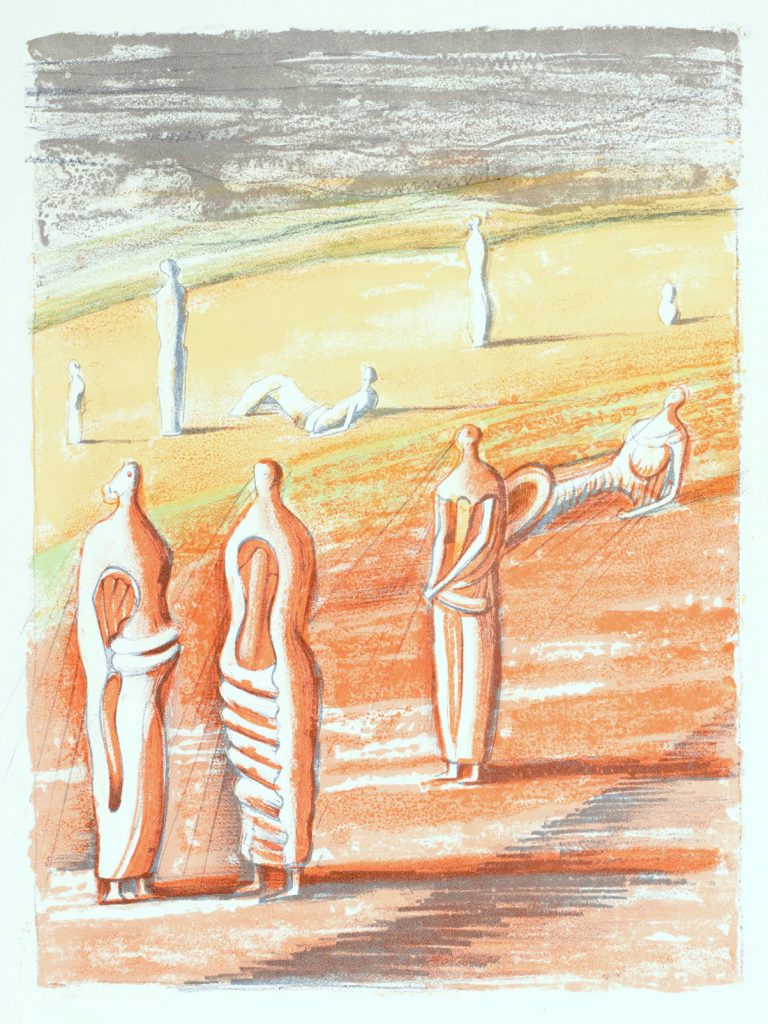

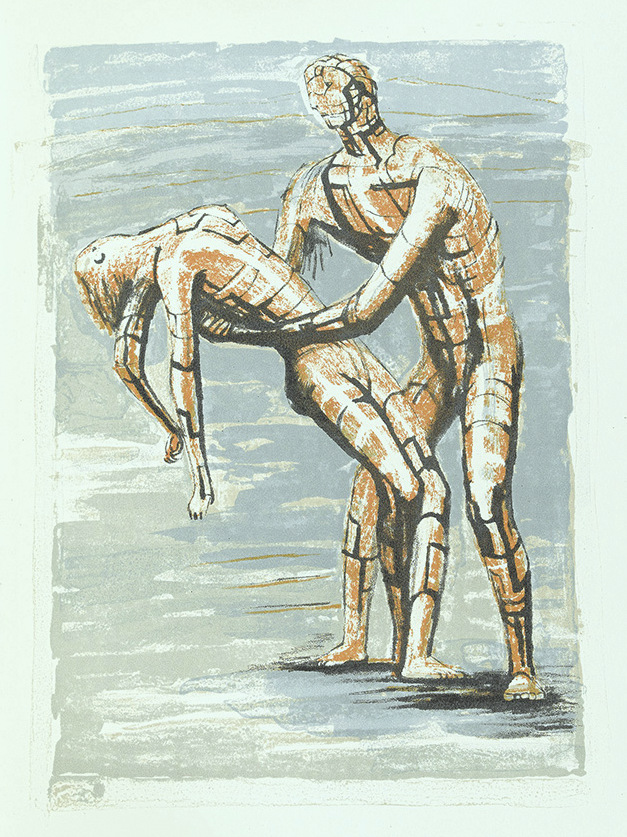

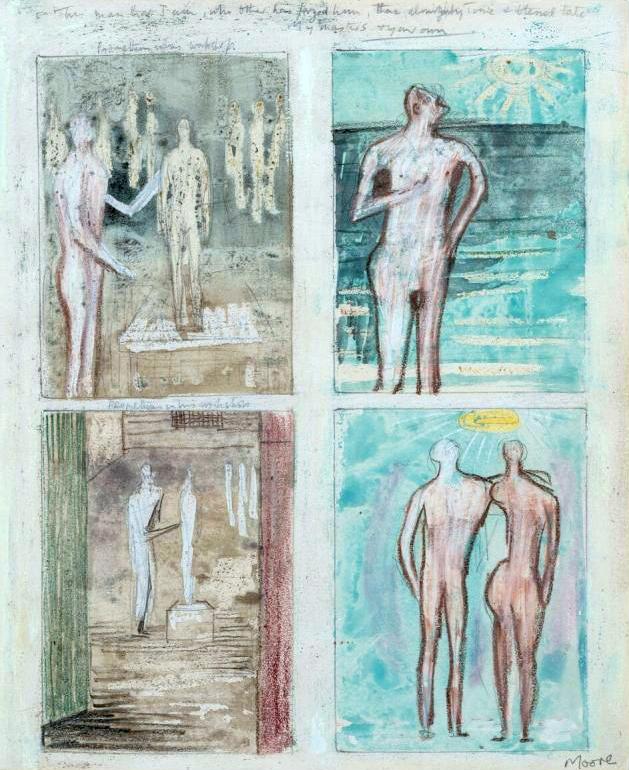

From 1948 to 1950 Henry Moore worked on illustrations for a new edition of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s poem, Prometheus, published by Henri Jonquières in 1950. It features fifteen colour lithographs and the text translated into French by André Gide.

This is an interesting era for Henry Moore, having been recognised in the 30s as a tallent, his shelter drawings had been popular with the public and had been printed in journals and newspapers giving him access to a newer audience. Though this book as a signed and limited edition, it continues

Cover thy sky, Zeus, With haze of clouds!

And practice, like boys,

who decapitate thistles, on oaks and mountains!

But I must leave my earth and my hut, which you did not build,

and my hearth, whose glow you envy me.

I know nothing poorer under the sun than you, gods.

You feed meagerly on sacrificial taxes and the breath of prayer,

Your Majesty, and starved, were not children and beggars or of hopeful fools.

Since I was a child, not knowing where to go,

my lost eyes turned to the sun,

as if there were an ear above it, to hear my lament,

a heart like mine, to take pity on the oppressed.

Who helped me against the arrogance of the Titans?

Who saved me from death, From slavery?

Haven’t you done it all yourself, Holy glowing heart?

And you glowed, young and good,

deceived, thank you for the salvation of the sleeping one over there?

Did not forge me into a man?

Almighty time and eternal destiny,

my lords and yours?

Did you think I should hate life, Flee in deserts,

Because not all boy-morning blossom dreams ripened?

Here I sit, forming people in my image,

A generation that is like me,

To suffer, to cry, to enjoy and to be happy,

And to ignore you, as I do!

The Liberty of Doubt by Ai Weiwei at Kettles Yard. Make of it all what you will. Some powerful stuff in show and Kettles Yard appears to have gone to war with Cheffins and their oriental department, spikey stuff.

It will take you no longer than 30 minutes unless you are deeply pretentious and it is much better than many of the deeply dubious shows they have been hoasting. It wasnt busy, though you have to book a ticket for the day, but not the time. Ive tried to be abstract about what I’ve shown so not to ruin it, but its not a retrospective and not full of work as the hype before buzzed on and the duration of the show. But you will walk away feeling that you’ve witnessed thoughtful activism.

Maharaja Duleep Singh

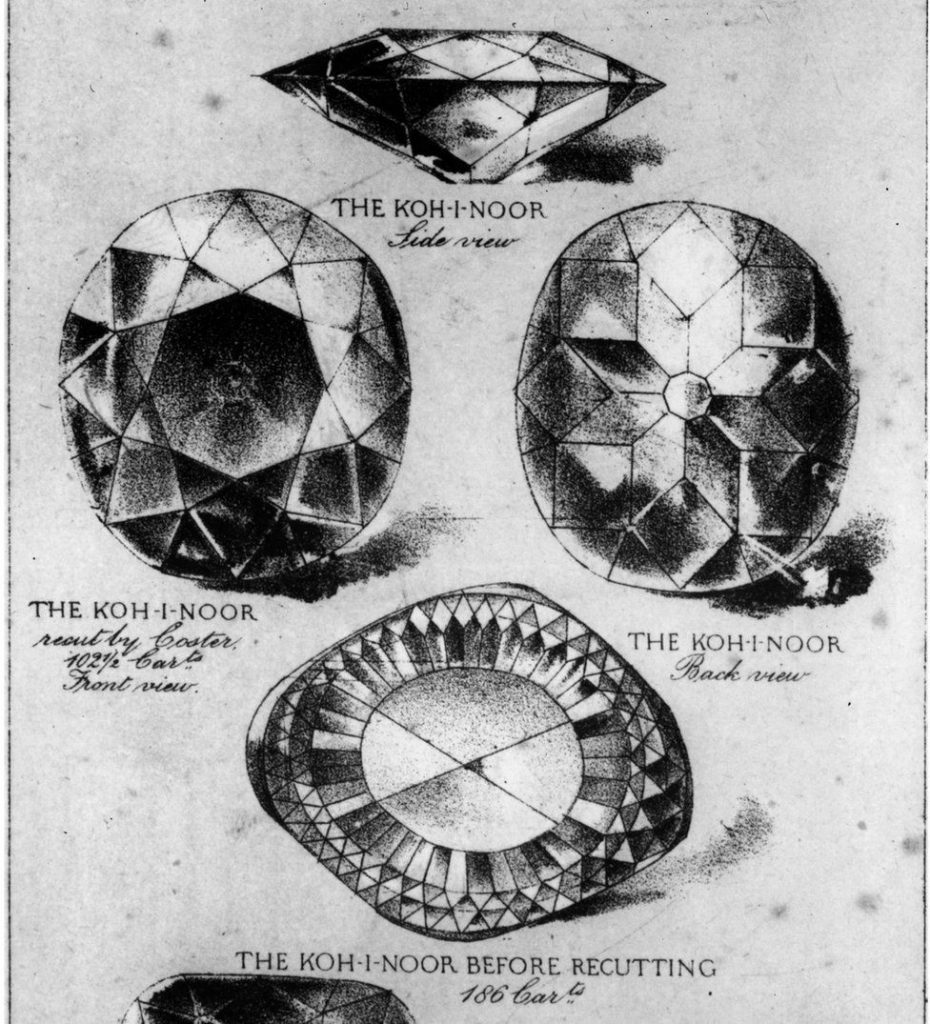

Maharaja Duleep Singh, the last true ruler of the Sikh Empire, and then owned the Koh-i-Noor diamond, was exiled to Britain, having been removed from his kingdom by the British East India Company. He was the last of his line to have been born in India.

As a child his mother was regent of the Punjab and after the Anglo-Punjab war with the East India company claiming the territory for the British, Sir John Spencer Login was appointed his guardian and set to anglicising this ten year old child by schooling him with other officers children. When he was eleven the young Duleeep Singh was forced to sign over the Koh-i-Noor to the East India Company, who gave it as spoils of war, to Queen Victoria.

Duleep Singh arrived in England in late 1854 and was introduced to the British court. Queen Victoria showered affection upon the turbaned Maharaja, as did the Prince Consort. Duleep Singh was initially lodged at Claridge’s Hotel in London before the East India Company took over a house in Wimbledon and then eventually another house in Roehampton which became his home for three years. He was also invited by the Queen to stay with the Royal Family at Osborne, where she sketched him playing with her children and Prince Albert photographed him.

After being welcomed into society, the sixteen year old, Duleep Singh was given a pension of around two and a half million pounds a year. He was an educated man and was a member of the Photographic Society from 1855.

He had many homes in Britain. First being bought a house by the East India Company in Wimbledon and then Roehampton, then he was moved out of the way of London to Scotland: to Castle Menzies, then in 1860, Grandtully Castle as well as Auchlyne House, and in 1861 when he became Maharaja he acquired Elveden Hall, Suffolk, with it’s 17,000 acres.

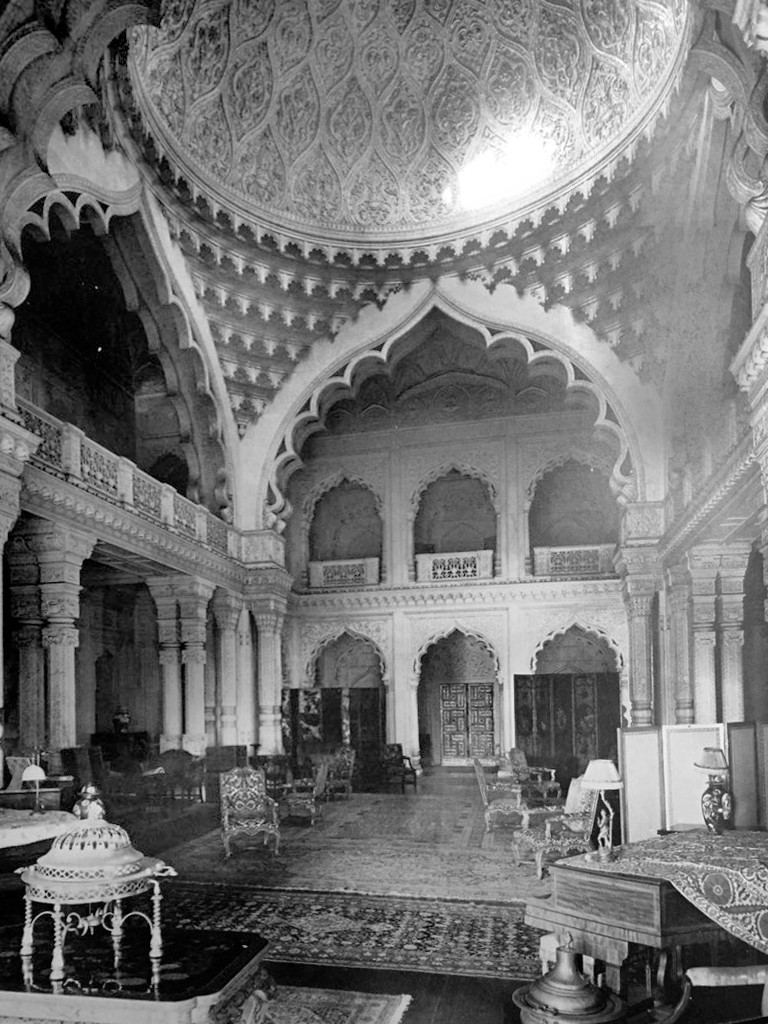

The original Elveden Hall was a Georgian building which the Maharaja Duleep Singh had enlarged in 1863-1870 by his architect John Norton in an Italianate style for the exterior and Indian style for the interiors, to resemble the Mughal palaces that he had been accustomed to in his childhood. He also augmented the building with an aviary where exotic birds such as golden pheasant, Icelandic gyrfalcons, parrots, peafowl and buzzards were kept.

Now the area is known for being the Thetford Centre Parks resort, being built on part of the estates lands.

After seasons of poor farming in the 1870s, vast over spending and political tensions in government, the Maharajah left Elveden and England in 1886 for India. He was however arrested in Aden, Yemen and forced back to Britain on fear he would be a political menis.

After the Maharajah’s death in Paris in 1893, the estate was sold off and bought by members of the Guinness family. They too fell on hard times and had abandoned the expense of living in the hall, and were living elsewhere on the estate. Its entire contents, including elaborate items owned by the Maharajah, were auctioned at Christie’s in May 1984.

During the Second World War the house and grounds were used by the American Air Force. Above is the large ornamental lake (that has been filled in) next to the water tower.

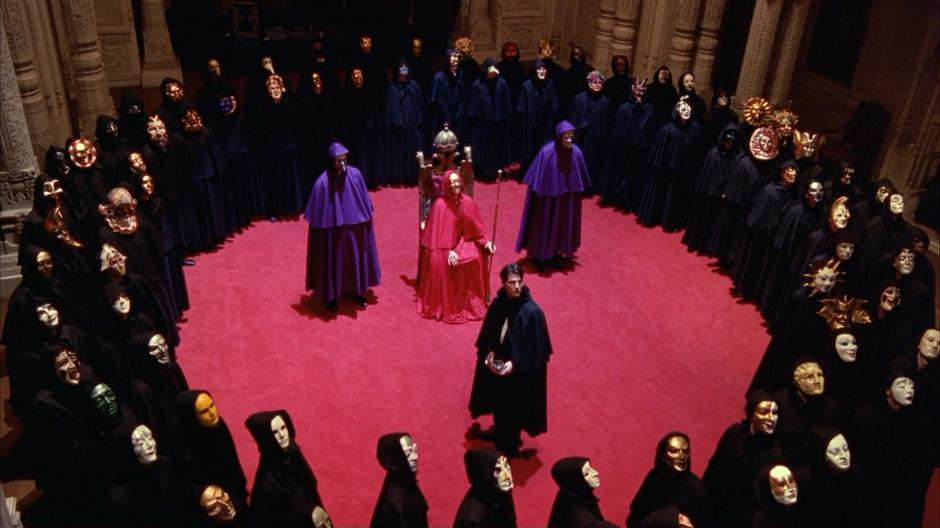

Since then, the Guinness family have rented the hall out for filming. Movies shot there include:

The Living Daylights (1987)

Gulliver’s Travels (1996)

The Moonstone (1997)

Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001)

Stardust (2007)

Dean Spanley (2008)

All the Money in the World (2017)

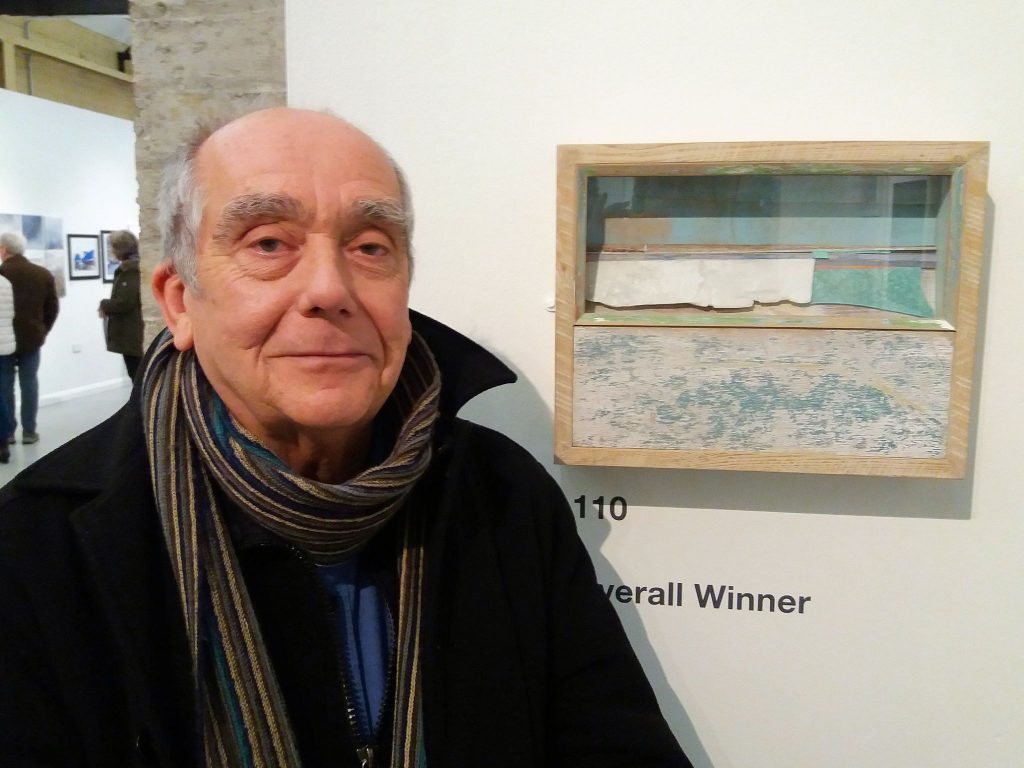

Born in Leytonstone, London he studied sculpture and art history at the South East Essex School of Art & Design. For over thirty years he divided his time between teaching in schools and colleges, working on art and design curriculum development and making sculpture, before retiring as a local education authority art adviser and inspector for art and design in 1997 to concentrate on making full time, when he had an exhibition at the Gordon Hepworth Fine Art (London and Exeter).

Gordon Hepworth exhibited a wide range of (mostly) Cornish based artists from Breon O’Casey, Clifford Fishwick, Peter Joyce and Graham Rich.

Geoff Bradford’s constructions in boxes are beautifully crafted – created using ‘objets trouve’ – they are made up of fragments of materials which have a beautifully eroded quality. They are small works which invite you to look into them closely and discover the echoes of memory and atmosphere which are trapped within.

BBC Visual Art

Geoffrey has also exhibited with his wife Sarah. Though these days he has moved into photography.

Geoffrey has also exhibited at the Open Eye Gallery (Edinburgh), New Millennium Gallery (St Ives) amongst others and has had several solo shows including The Newport Museum and Art Gallery, the Lund Gallery (Yorkshire) and Brecon Museum and is currently represented by a number of galleries in the North East and Scotland. He was a regular finalist in The National Eisteddfod and a 1994 prize-winner at the Tabernacle (MOMA) in Wales.

Here are some photos from instagram I taken recently taken on walks around.