This is a movie that is rather hard to come by, but has made it way on to youtube. It was suggested to me by a friend and it is remarkably camp but good in my view.

Author: Robjn Cantus

Nan Youngman in Cambridge with Robjn Cantus

25th June 2025, 6.30pm – 8.30pm

Cost £10 per person (£12 with donation)

Venue Studio Space at David Parr House

Book via the David Parr House website

Join Robjn Cantus for a salon talk exploring the remarkable life and legacy of Nan Youngman, an artist, educator and key contributor to Cambridge’s mid-20th-century cultural identity.

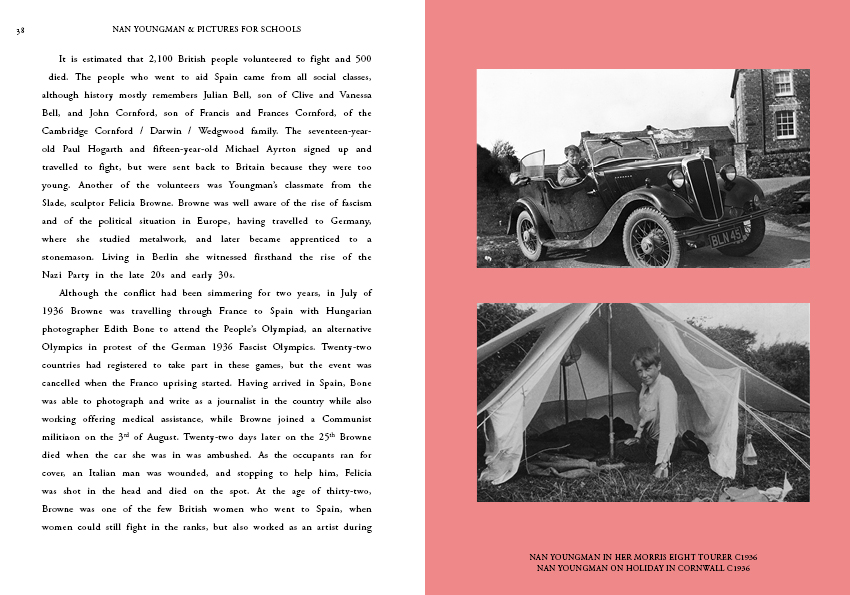

Nan Youngman was an artist who lived most of her life in Cambridge. Together with her partner, Betty Rea they had moved to Huntingdon during the war, originally living in a caravan and then later, moving to Godmanchester and then Papermills, by the Leper Chapel on Newmarket Road.

She was a bold educator who strived to change the perception of art in schools from a pastime into a necessity. She worked for Henry Morris the pioneer of the Village College and who had employed Bauhaus architect Walter Gropius and his business partner Maxwell Fry to design Impington Village College.

Nan Youngman founded Pictures for Schools, a series of exhibitions were the counties of England were invited to buy paintings by the best artists in Britain, and later on prints. These works would then be hung in schools to inspire children and worked in with other lessons on education.

In Cambridge they met and had many connections, with friends like Tirzah Garwood, Elisabeth Vellacott, Lucy Carrington Wertheim and Bryan Robertson, who ran the gallery at Heffers bookshop for a time. It was due to Robertson’s intervention that Nan and her friends set up the Cambridge Society of Painters and Sculptors.

Together with many more people, they helped make Cambridge a more artistic place in the 1950s, 60s and 70s.

Robjn Cantus is a writer, collector and researcher based on the edge of Cambridge. Robjn is known for his detailed work on 20th-century British art and artists. His published books include Nan Youngman & Pictures for Schools (forthcoming, 2025), Great Bardfield Illustrated: A Bibliographic List (2024), Looking at Life in an English Village: Edward Bawden & Great Bardfield (2022) and Before and After Great Bardfield (2021).

The talk will be followed by a Q&A, light refreshments and the chance to purchase a signed copy of Robjn’s new book at 10% discount on the night. Please note, by purchasing a copy of the book with your ticket you get a 15% discount on the book.

I should add I am doing this talk for free, so that all your donations do to the David Parr House.

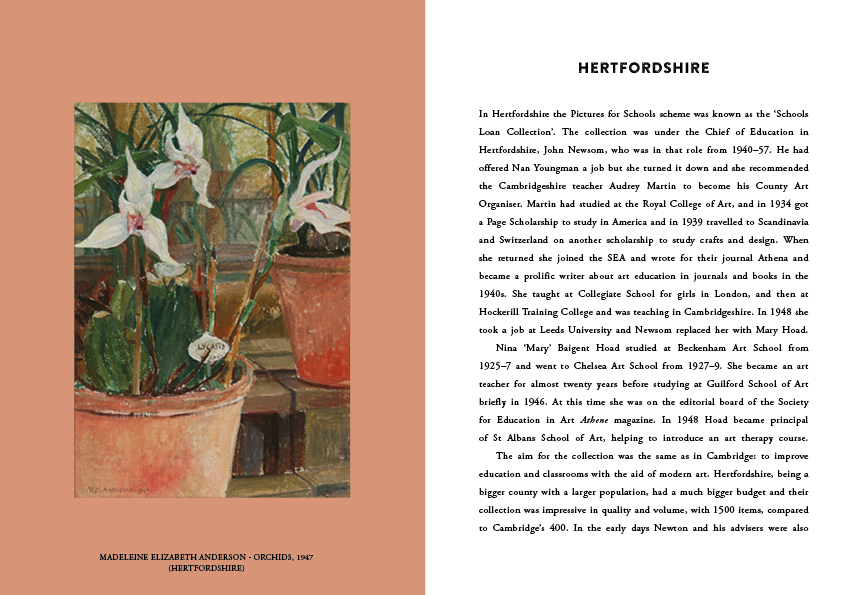

Margaret Kaye, in a professional career in glass and textiles between 1937 and 1985, executed commissions for windows in Chichester, in York, for the Boltons and Radnage, as well as for a mission in Formosa (now Taiwan). She also carried out stained-glass restorations for the National Trust during the 1930s; at Stourhead, in Wiltshire, on the late 14th-century window of the great hall at Rufford Old Hall, and at Penshurst, Aylesbury and Woburn, among other houses.

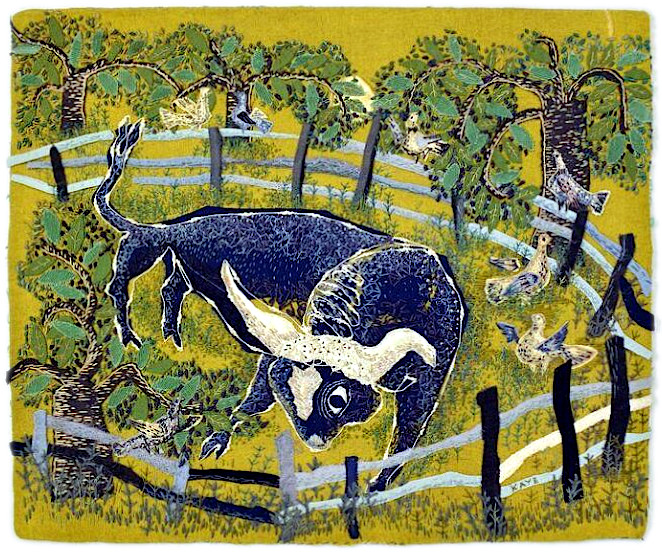

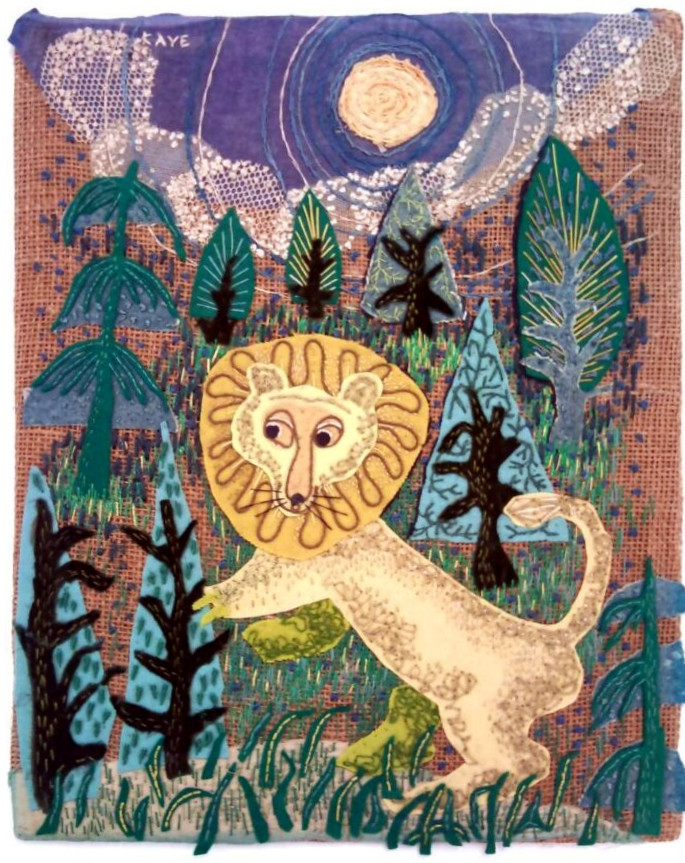

In the field of textiles, she established a highly personal and individual style in the making of hangings for domestic interiors. These were splendid in their rich colour and texture, combining appliqué, fabric collage, strands of thread, dyed lace and embroidery, in bold and inventive designs evoking the palette of artists like Georges Rouault or Antonio Clavé, who were among her favourites. The Victoria and Albert Museum have four such pieces in their collection, Lion in a Forest and Bull and Pigeons, both of 1949, and The Cat and the Owl and Pigeons, both of 1951.

For a number of churches and cathedrals, she created altar frontals and copes. She executed ecclesiastical furnishings for Marlborough College Chapel, and for Winchester, York and Chichester Cathedrals, as well as for many English churches and chapels. One of her major commissions was that for the Queen’s personal gift to the cathedral in Accra, Ghana.

Margaret Kaye was born in 1912, and was first trained at Croydon School of Art, then attended the Royal College, specialising in fabric collage and stained glass, which she was taught by the celebrated Martin Travers. Later married to Reece Pemberton, the stage designer, and always herself passionate about the theatre, she designed accessories for ballets for Marie Rambert at Sadler’s Wells.

A new development during the 1940s was her activity as a painter. In many ways, her approach to fine art was related to her textiles. For her collage pictures, which were highly abstracted but suggested landscape, she used found objects, pieces of cork, leaf and bark, bits of fabric, cardboard and torn photographs, modifying them with watercolour or gouache, always with a rich and warm colour sense, characteristically in browns, ochres, creams and reds. Her work attracted the attention of Sir Kenneth (later Lord) Clark, who introduced her to the art dealer Henry Roland, and from 1949 to 1977 she had regular solo exhibitions at Roland, Browse and Delbanco in Cork Street.

Having acquired a weekend house on the edge of Tilford Common in Surrey in 1955, she and her husband moved there from Hammersmith shortly before he died in 1977. From 1976 to 1989 Kaye had four exhibitions at the New Ashgate Gallery in Farnham. Her collages were exhibited widely in mixed shows in Britain, the US, Australia and South Africa. Her work is in many public collections including those of the Contemporary Art Society and Manchester City Art Gallery.

Kaye taught full-time for a period at Birmingham College of Art, then, in London during the 1960s and 1970s, part-time at Camberwell and St Martin’s. Her former pupils remember her as “a wonderful teacher, always on the side of the students”. Having no children of her own, she valued her association with young talented people. In her later years she gave a Travelling Prize annually in Fine Art or Textiles to students at West Surrey College of Art.

This artical on Richard Chopping was published in The Book & Magazine Collector in 2001. It gives a very interesting view into his work and features an interview with Crispin Jackson as well.

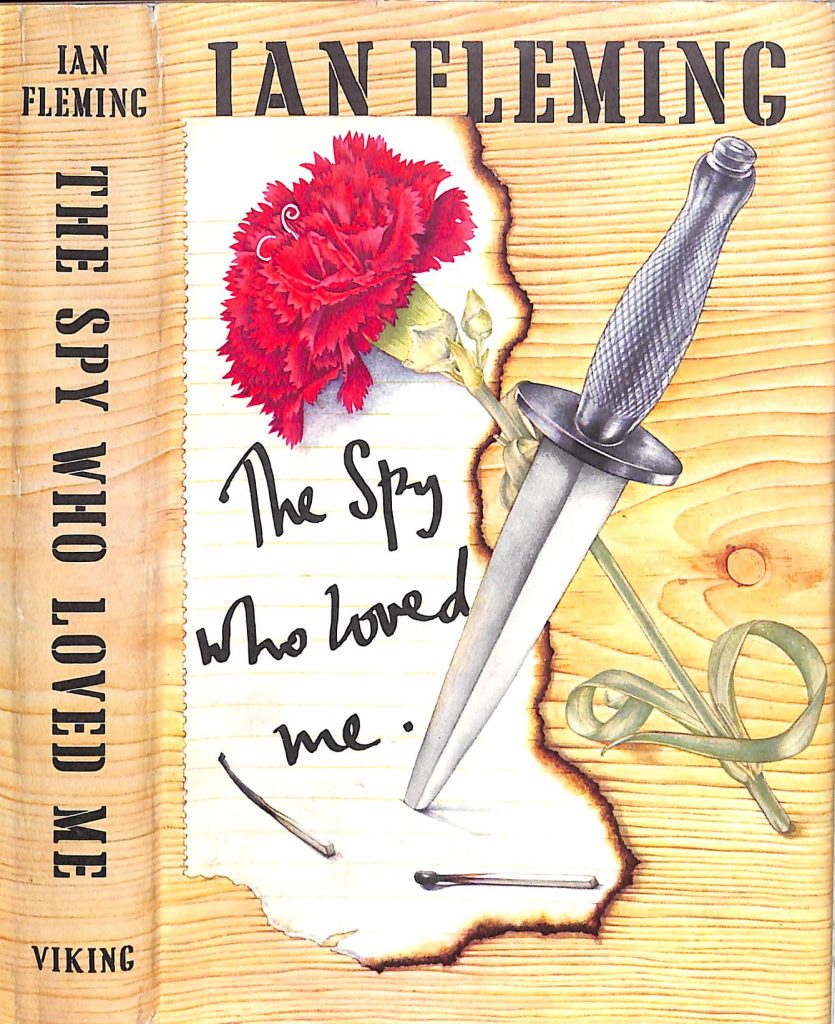

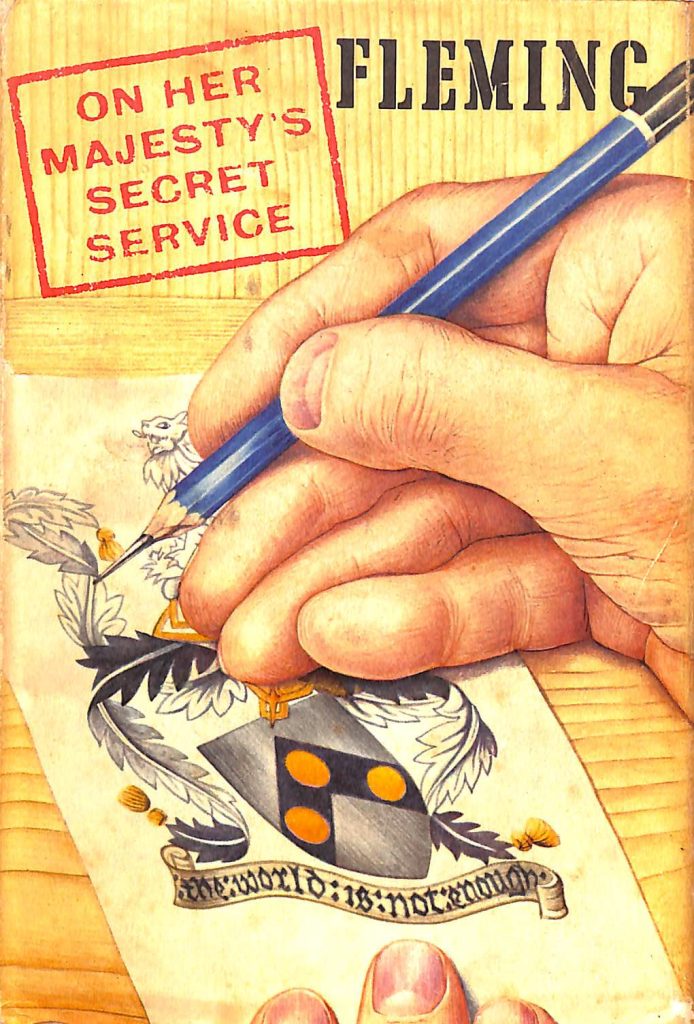

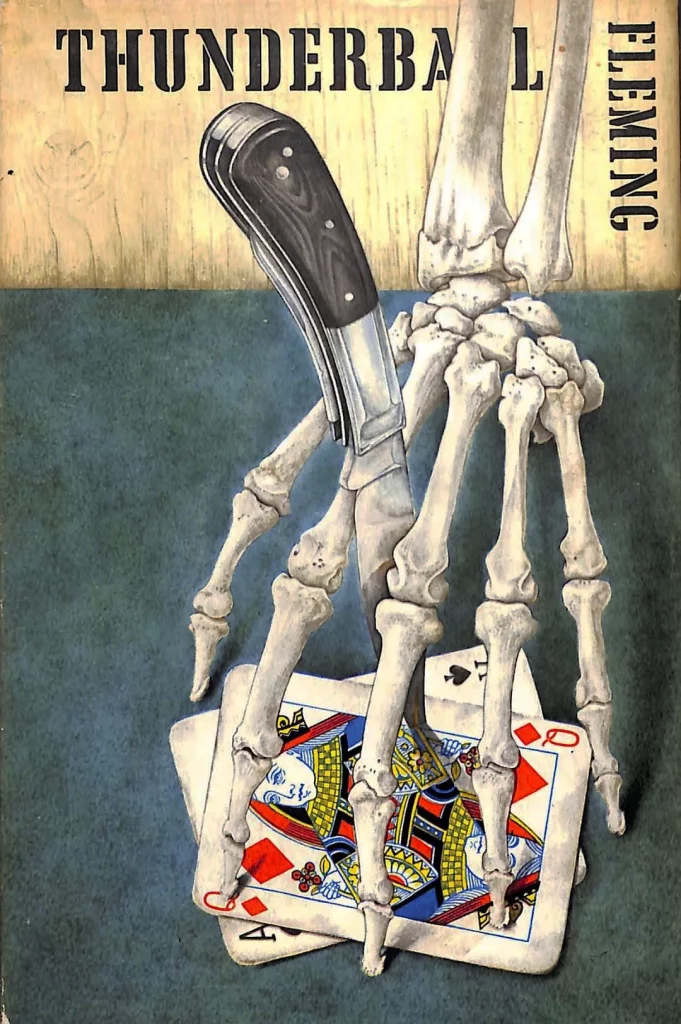

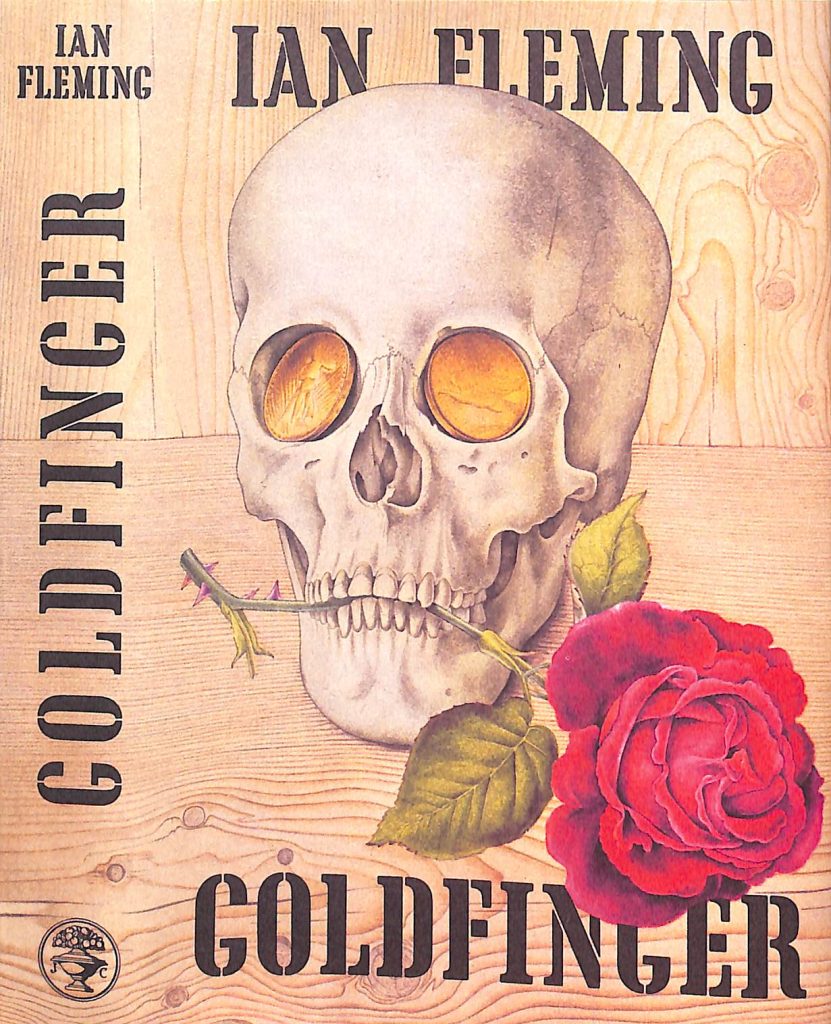

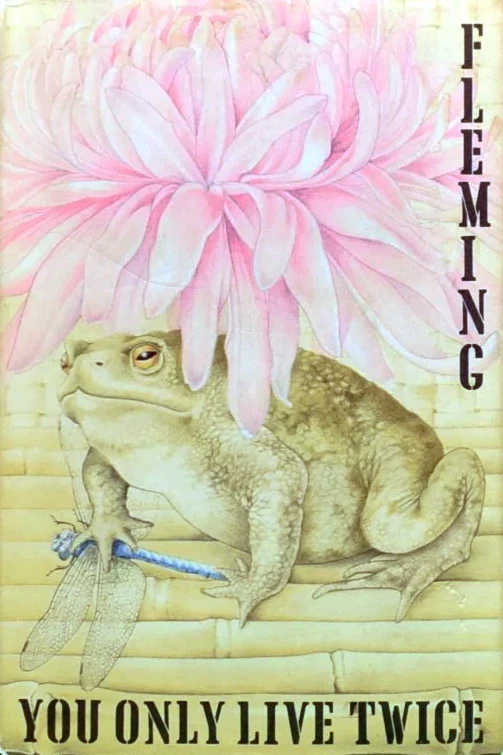

Regular readers will recall that, for the January issue, I wrote a piece on Ian Fleming’s James Bond’ books, in which I reserved particular praise for the dustjackets of Richard Chopping. “What is it that makes these jackets so unforgettable?” I asked. “Their sheer realism is certainly a contributing factor But the skill is more than technical. In his best jackets From Russia, With Love, Thunderball, You Only Live Twice, Goldfinger, The Man with the Golden Gun Chopping always incorporates contrasting images of beauty and ugliness, innocence and corruption.

His pictures are superficially appealing, but they have a chilling sub-text which also compels our attention and admiration. They are true works of art.”

Unfortunately, I went on to describe the splendid Goldfinger jacket in the following terms. “With Goldfinger, a rose is again used to offset the main image a skull with gold sovereigns in its eyes.” Days after the magazine reached the shops, I received an unexpected letter handwritten in vast black letters on paper which was crossed with thick black lines “It is nice to read your comments on my work, wrote my correspondent, “but my pleasure is tempered by the inaccuracies the article contains… Those gold coins on the cover of Goldfinger are American dollars and not sovereigns, which would have fallen inside the skull.” He went on to point out that “the flower behind the toad [on the jacket of You Only Live Twice] is a chrysanthemum and not a ‘pink lily”, as I had described it. “Either whoever wrote the article is no botanist, or I failed in my realism.” Alas, the fault was mine. The letter ended: “I expect people think I am dead. My sight is very bad” hence the special writing paper and heavy, black handwriting “but I am alive and kicking. The latter statement seemed to me to be some-thing of an understatement. I wrote back in some excitement suggesting an interview. “Yes, an interview would be fun, Chopping replied, ending with the concilia-tory note: “All is forgiven.”

For various reasons, the interview had to be postponed for some months, but I finally got to speak to Richard Chopping early in the autumn, and the highlights of our fascinating conversation are presented below. However, I feel that I must offer a few introductory paragraphs about Richard Chopping’s career, simply because there is so much more to it than just the “Bond jackets, lovely as they are. Indeed, in the course of his 83 years, Chopping has collaborated with Allen Lane (“a Napoleon character”) and John Hadfield, and has been friends with Frances Partridge, Angus Wilson, Francis Bacon, Kathleen Hale, John Minton, and many other well-known authors and artists.

His bibliography includes children’s stories, natural history studies and two extraordinary Ortonesque novels. Indeed, if you collect ‘Bond’, Penguins, children’s books, The Saturday Book, Sixties fiction or just beautiful artwork, then you cannot afford to ignore Chopping.

Richard Chopping was born in Colchester, Essex, on 14th April 1917. His family produced ‘the whitest flour in Essex, and the Chopping mill can be seen from his house on the banks of the River Colne. Chapping’s first book was this survey of Butterflies in Britain. The cover designed and executed by Denis Wirth-Miller.

In a signed copy of You Only Live Twice, Chopping wrote on the end papers of the book:

Fleming had very little to do with this cover. I chose the objects and displayed them as I wanted them. He used to tell me what he wanted but I got fed up with that and said “I must read the book first.”

He said “Oh you don’t want to do that, it’s all rubbish.” However I did and decided what I would do although I agreed with him. The Chrysanthemum was difficult, but I had a dragonfly. But the toad did represent difficulties. Eventually I found one by asking around. It came from a friends daughter who taught [in a] school in London…

PS Fleming was rather mean. When I asked him if I could have a Royalty on the books instead of him buying my pictures outright for pea-nuts… before I had finished my sentence “No my company wouldn’t wear it”. So I upped my fee thereafter, but they were still cheap.

James Bond was born January 3. 1952, at Goldeneye, the Jamaican retreat of 43-year-old journalist and former intelligence officer lan Fleming “Horrified by the prospect of marriage and to anesthetize my nerves,” wrote the author, “I sat down, rolled a piece of paper into my battered portable and began.” After seven weeks of relaxed, though steady, writing (a process Fleming described as “roughly the equivalent of digging a very large bole in the garden for the sake of exercise”), Casino Royale finished. Still, the author was cautious: “When I got back to Low nothing with the manuscript. I was too ashamed of it. No publisher wanted it and, if one did, I would not have the face to see it in print”. Fleming’s self-deprecation was partly the studied nonchalance or a gentleman dilettante living the upper-class ideal of effortless accomplishment. But it also revealed real anxiety. With Casino Royale, Fleming had broken a lifetime of literary repression and written the book he had long promised, the “spy story to end all spy stories.”

Fleming modestly, but quite deliberately, let a friend in publishing know he had written a book. Within months the book was accepted for publication and Fleming’s caution and self-deprecation vanished. He ordered a gold-plated typewriter and threw himself into promoting his book. Until his death in 1964, Fleming returned each January to Golden-eye, where, writing at the leisurely pace of fifteen hundred words a day and never looking back at what he had written the day before, he would produce another James Bond adventure.

Famously, the name James Bond came from the author of Field Guide of Birds of the West Indies (1947).

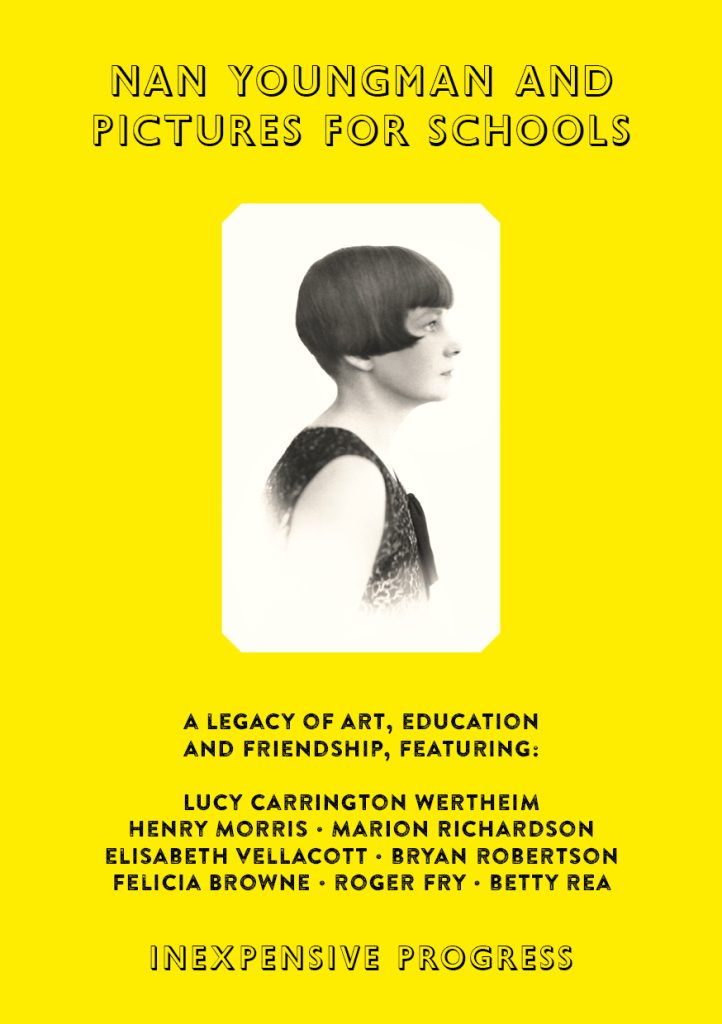

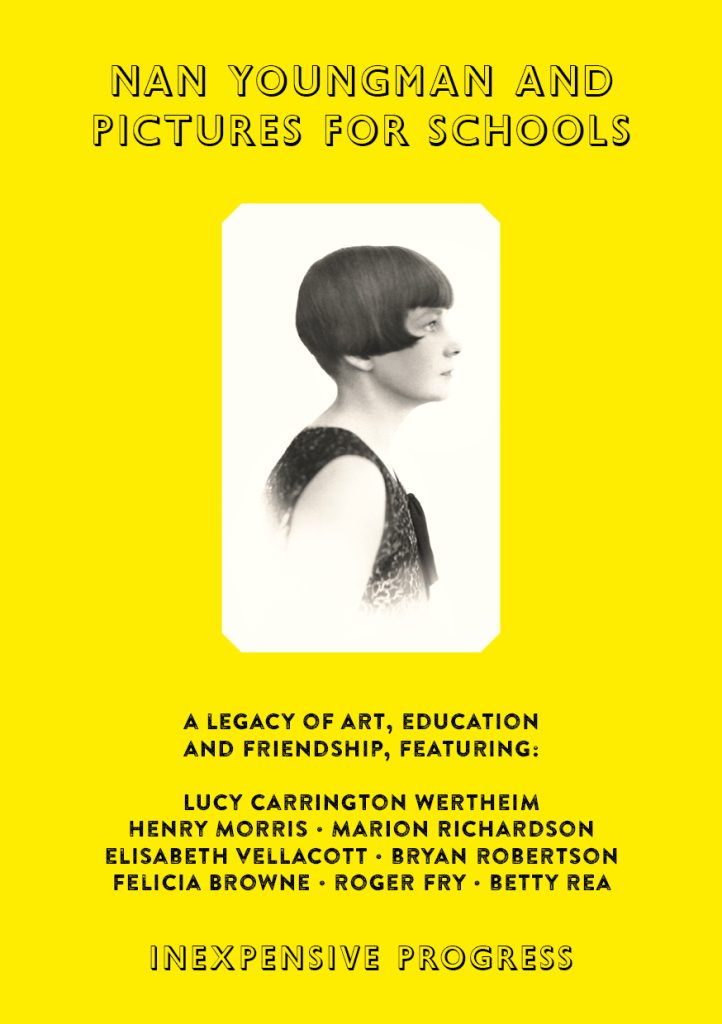

Nan Youngman & Pictures for Schools

220 page Paperback, click the link below to order direct to your door

Buy here – First Edition (£25+£3P&P)

Nan Youngman & Pictures for Schools by Robjn Cantus

Not sold on Amazon

Nan Youngman’s life was guided by the friends she made and each of these people affected her future in different ways: from her family, her time at the Slade School of Art and then teacher training under Marion Richardson; to meeting Betty Rea, her partner.

In the 1940s Nan was working as the Education Art Advisor under Henry Morris for Cambridge County Council where she was able to trial a plan to bring paintings into schools with the purchase of a L.S. Lowry painting; aiming for something more ambitious than the Schools Prints lithographs.

These modern paintings were used in schools to develop the creative mind, as teaching aids and social education. To make it a national scheme Nan organised annual art exhibitions from 1947-1969 so the Councils of England, and later Wales, could buy the best of contemporary British Art.

In this volume you can discover the rise and fall of some of the Councils’ collections, as well as the biography of Nan her personal life and the people she knew, such as: Roger Fry, Henry Tonks, Bryan Robertson, and Lucy Carrington Wertheim.

This volume is released as a limited of 50 numbered copies and then a standard first edition with the typical yellow Inexpensive Progress cover.

Recently I have been working on a duel biography of Nan Youngman and her role in Pictures for Schools. It is the story of her life through the people she knew and how it ended with each person gifting areas of knowledge and confidence for her to form the Pictures for Schools exhibitions – an annual event where councils from across England (and later Wales) could buy art to hang in schools to inspire children. This idea was quite radical for the post war era – to put real paintings in front of children and to banish reproduction prints of famous artworks.

Youngman was working for Cambridgeshire Council at the time as the Art Adviser under Henry Morris in the department for education in the council. Cambridgeshire invested in a Lowry in 1945 to get the experiment started and over the next few years with the help of the Society for Education through Art the exhibitions were formed in 1947 running until 1969.

After 1969, the momentum for many of the council’s collections started to slow down and by the millennium many of the collections of works into storage.

Cambridgeshire, the founder of the scheme was the first to sell of their collection of works due to a strange situation of the city – it was one of the few towns in the country not to have their own art gallery. Many of the museums in the city were owned by the University, including Fitzwilliam Museum. So with a collection of valuable mid-century art and nowhere to display them, they were sold off at auction. Soon Hertfordshire did the same after a large public consultation and then Nottingham sold off part of their collection via the Fry Art Gallery in Saffron Walden. Derbyshire took some effort to re-home their more famous works to institutions around the country but the rest of the works were auctioned off under the stealth guise of them being the collection of Barbara Winstanley, the art advisor who helped found the collection.

All this is very much in my mind but it comes at a drastic contrast to schools and education today. There is a new scheme to put art into schools, and as good as this sounds it also has a depressing reality. These artworks are not to be real paintings, or even prints, but photographs of famous works of art displayed on a TV screen that is located in key points of a school.

This scheme is run by the charity Art In Schools and is a resource to help children see art. They offer works by Picasso to George Stubbs, and even Andy Warhol. The key failing of this nice idea is that real Warhol prints are larger than you would expect – they are quite powerful works in dimension and also the texture of how they are printed. In the same way as they don’t really translate well in a book, a TV screen can never do them justice. In order to promote the idea the charity asked Damien Hirst, Bridget Riley, Cornelia Parker and Antony Gormley to suggest their favourite works of art to be on show.

The brochure for the Charity highlights they are: Closing the Art Gap that has happened in the underfunding of schools, how they are helping disadvantaged areas by bringing art into the classroom and they encourage children to think about art as a career and help with the national syllabus. They also add that seeing art supports mental health in children and promotes equality and diversity. These are more or less the original ideas of Youngman’s scheme in 1945. But in short there is no way the texture; scale or tonality of a painting can be judged from a digital screen.

Underfunding in the arts is a problem and cutting these services are seen as an easy way for cash strapped councils to save money as the true impact of the ideas are harder to grade. The problem has got so bad that Sotheby’s Auction house has been approaching councils in England to Value their most valuable objects as a free service, in the hopes they will auction them off. This is a gateway drug into councillors looking at the short term gains of making money against the benefits to the culture of their towns.

When Simon Wallis, the director of the council backed Hepworth Wakefield gallery was asked about Sotheby’s scheme he said:

“If works are sold to attempt to mitigate financial shortfalls for local authorities, the public permanently loses a major valued resource, generations in the making, and the underlying structural problems of local government funding will remain fundamentally unchanged.”

It’s a hard scheme to judge because at the moment standards are so low that anything is better than nothing. But it feels like the ambitions of councils and the opinion of the wider public towards the arts have been set too low.

Councils approached by Sotheby’s include Derby City Council, which has a collection of paintings by 18th century artist Joseph Wright that were valued by the auction house for insurance purposes at £64m in 2012. In 2024 Suffolk council cut the arts budget to the county by £500,000 but after a public backlash they cancelled this plan and tried to promote the cut not happening that the council had gained £500,000 for the arts.

It is all a trend in the wrong direction while looking to be progressive.

- Nan Youngman & Pictures for Schools will be out in May 2025.

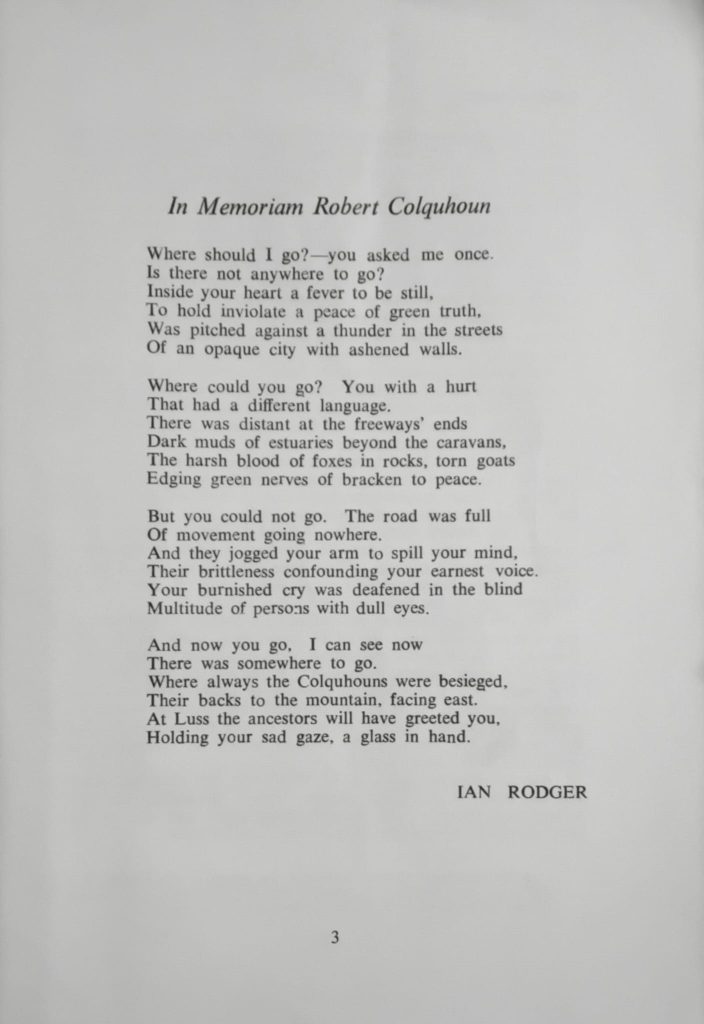

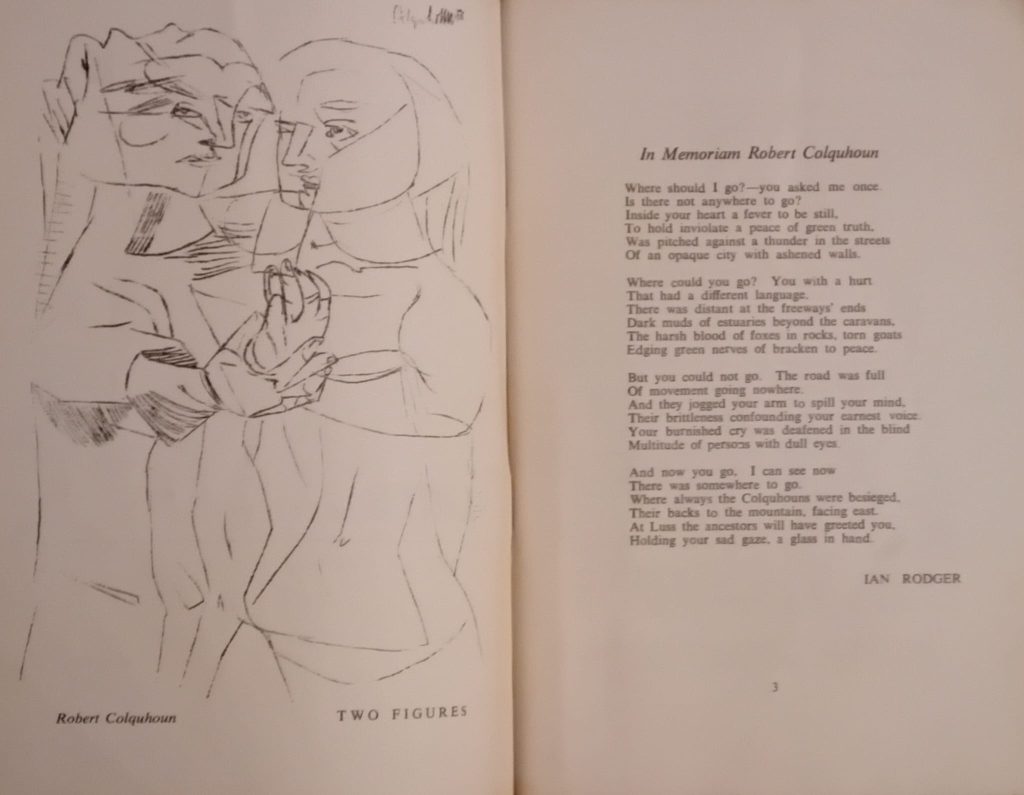

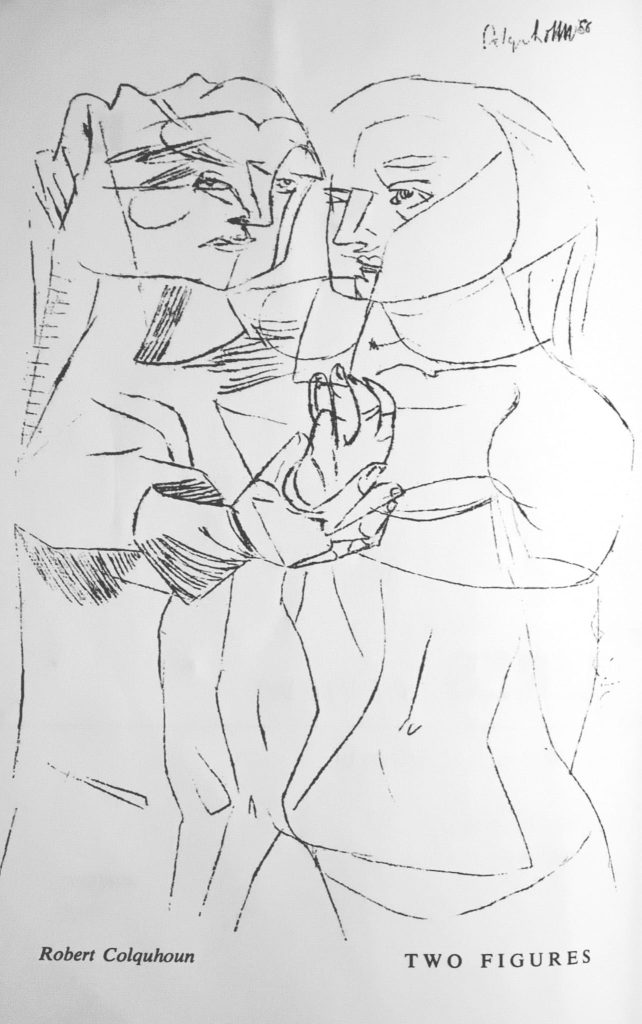

A memorial poem to Robert Colquhoun by Ian Rodger, from the Scottish Lines Review #19 in 1962 with a drawing of Two Figures.

In Memoriam Robert Colquhoun

Where should I go? you asked me once.

Is there not anywhere to go?

Inside your heart a fever to be still.

To hold inviolate a peace of green truth.

Was pitched against a thunder in the streets

Of an opaque city with ashened walls.

Where could you go? You with a hurt

That had a different language.

There was distant at the freeways’ ends

Dark muds of estuaries beyond the caravans,

The harsh blood of foxes in rocks, torn goats

Edging green nerves of bracken to peace.

But you could not go. The road was full

Of movement going nowhere.

And they jogged your arm to spill your mind,

Their brittleness confounding your earnest voice.

Your burnished cry was deafened in the blind

Multitude of persons with dull eyes.

And now you go. I can see now

There was somewhere to go.

Where always the Colquhouns were besieged,

Their backs to the mountain, facing east.

At Luss the ancestors will have greeted you,

Holding your sad gaze, a glass in hand.

IAN RODGER

A look at the various wood-engravings and the watercolours that followed after Eric Ravilious’s commission to make designs for London Transport’s Green Line.

Lucy Marguerite Frobisher was born in Leeds in 1890. She studied at the Bushey School of Painting and in 1920 was appointed secretary of the school, founded by artist Lucy Kemp-Welch who became her lover. They worked together and unusually, are buried in the same grave.

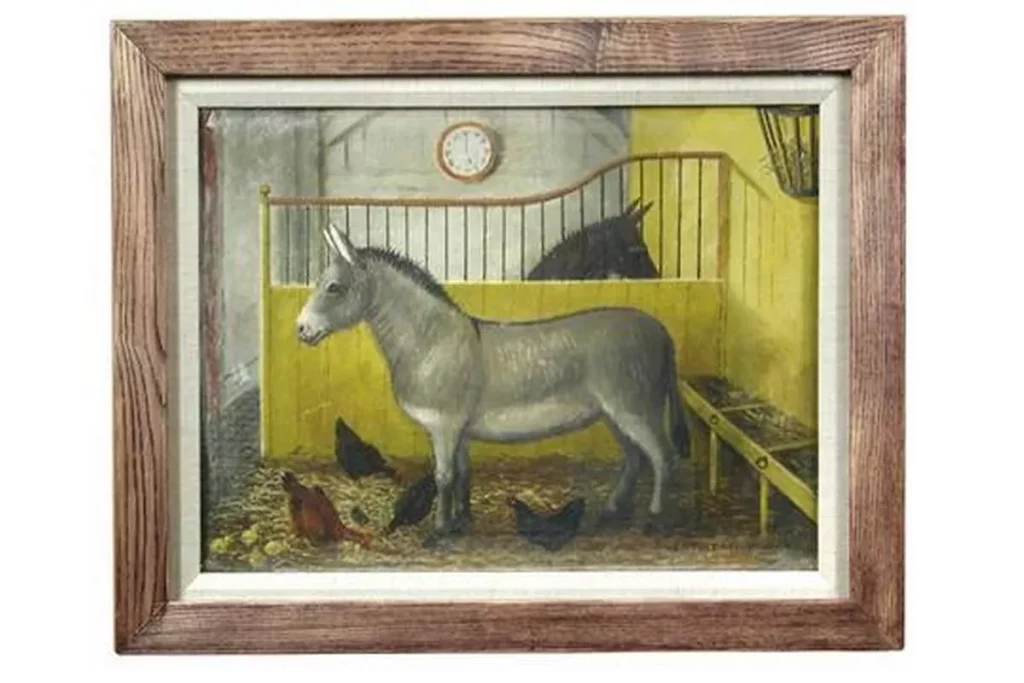

Kemp-Welch had been taught by Hubert von Herkomer, and in 1905 took over the running of his art school, renaming it the Bushey School of Painting. In 1928 Frobisher took over and renamed it once again, as the Frobisher School of Painting. The school focused on Landscape and Animal painting.

Over time Kemp-Welch has become famous for her paintings of animals, but it is curious that Frobisher took such a back seat in her artistic life.

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Recently Lucy and Lucy’s grave was restored by locals.

This is just a short blog about something that appears in two works and shows off Edward Bawden’s eccentric lavish life with his Rococo easel. In the painting below, by Eric Ravilious of Edward painting in his studio, it looks unlike most young artists rooms today, with a lavish mirror, Victorian bust and a dress mannequin. At the time this was painted, Bawden was five years out of art school.