Jean Iris Ross (Cockburn) (1911-1973) had gone to Berlin in 1930 to be a film actress in Weimar Republic. At this time the war ravaged Germany had become a liberal and cultural beacon for films, as they were made with less censorship and on a budget with great creativity. Although not a utopia for the masses due to inflation, there was work to be found in the music-hall cabaret bars of Berlin.

Having had a liberal education, left wing parents, and fled a Swiss finishing school to study at RADA, acting was the hope at this time in Ross’s life. However in Berlin she would share a boarding house with a young writer called Christopher Isherwood who would change the public perception of her life forever. Through Isherwood’s pen, Jean Ross metamorphosed into Sally Bowles (1937) over the course of three years Isherwood penned the novella that was to be the tinderbox to Mr Norris Changes Trains (1935) and The Berlin Diaries (1939). Although Isherwood abstracted Ross’s life and mannerisms, there were many facts in the book that were based on reality, she was a cabaret singer – though not a good one. She did come from a rich family and she did have an abortion before leaving Berlin.

A communist loyal to Stalin living in London she had a relationship with Claud Cockburn and had a daughter, Sarah Cockburn who wrote detective novels. Isherwood and Ross would remain friends and in October, Ross got Isherwood a job at Gaumont-British Studios (where Hitchcock filmed his movies). Isherwood was working under the director Berthold Viertel. Isherwood’s first experience in the film industry provided the material for Prater Violet (1945). (After this job Isherwood moved to California again to live above Viertel’s garage for two years.)

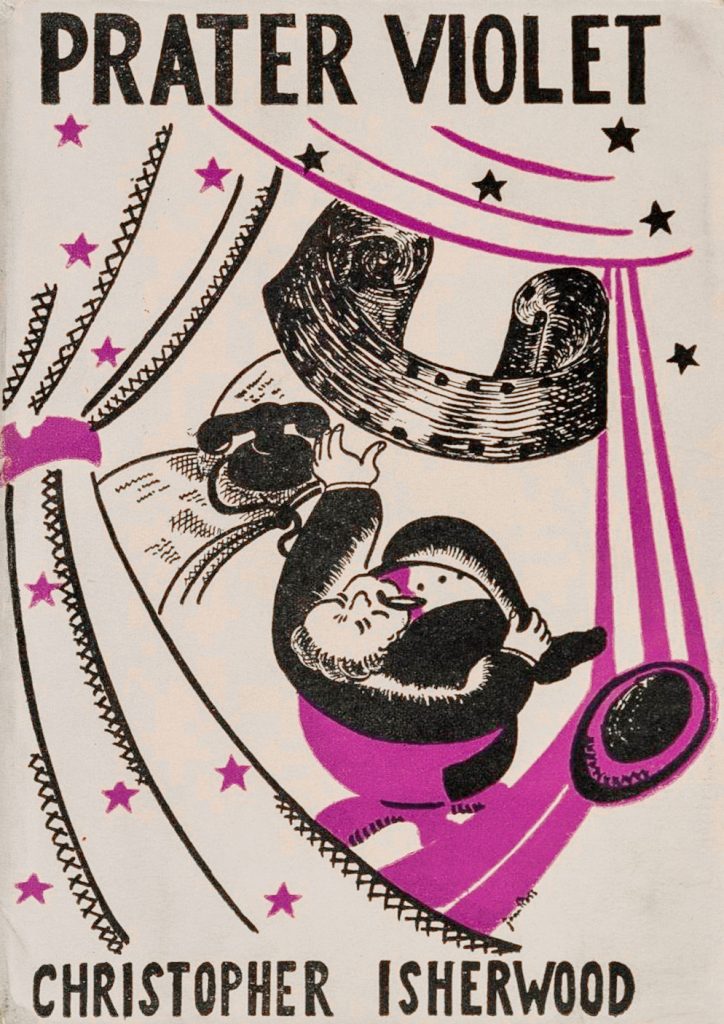

Knowing that Jean Ross and Isherwood were still in communication at this point in 1945 is important as it seems that Ross designed the dust jacket for the British edition of Prater Violet. Thought there isn’t a great deal of evidence Jean Ross became an artist in any other way, her sister Peggy was studying painting and sculpture at Liverpool School of Art around this time and so may have helped either with inspiration or advice. The dust jacket design is signed Jean Ross above the R in Isherwood.

The design also has the feel of some of the Hogarth Press dust jackets designed by Vanessa Bell for her sister’s books. Maybe because the Hogarth Press had published books by Christopher it was a conspiracy to make Prater Violet look like this? At this point it’s just conjecture but I think it can’t be denied they look similar.

It is interesting that the design of this cover isn’t noted by anyone, and that it seems to have been forgotten from history. The bulk of Ross’s life is that of a journalist and mother. Although she was tainted with the legacy of Sally Bowles, this probably wouldn’t have bothered Ross if it only stayed as a book. However when Isherwood’s works were turned into the play I Am A Camera, Sally took on a more flamboyant tone and her role was written as more self obsessed. Then when that stage play became the film Cabaret, Ross tried to disassociate herself from the caricature she had become. Ross’s strong political views clashed with Isherwood’s impassive observations of Berlin and how he wrote Sally, with Isherwood writing that Sally was self obsessed and at times flippantly anti-semitic.

Ross and writer Isherwood met a final time shortly before her death in London. In a diary entry for 24 April 1970, Isherwood recounted their final reunion:

I had lunch with Jean Ross and her daughter Sarah [Caudwell], and three of their friends at a little restaurant in Chancery Lane. Jean looks old but still rather beautiful and she is very lively and active and mentally on the spot—and as political as ever … Seeing Jean [again] made me happy; I think if I lived here I’d see a lot of her that is—if I could do so without being involved in her communism.

Christopher Isherwood – Liberation Diaries, Volume Three: 1970-1983

Ross died in 1973 in Richmond aged 61.