Keith Vaughan – An Orchard by the Railway, 1945

Here is an account from Keith Vaughan’s diary of his Victory in Europe Day. As many in the cities danced and cheered in the streets Vaughan was on the fringes and knew of the news too late. From Keith Vaughan – Journals, 1939-1977:

They had no wireless in the cottage where I had supper, so I didn’t hear the nine o’clock news. Walking back to the camp afterwards, the first sign of anything unusual I noticed was a string of small triangular flags being hoisted up across the road by some workmen. The flags appeared quite suddenly out of the leaf-laden boughs of the chestnut, crossed a patch of sago-coloured sky, and disappeared in the dark foliage of another tree. They looked surprised to be there. They were not new flags. They had flapped for a jubilee and a coronation and numerous local festivals, and now they seemed to be getting a little tired of it all. They were faded and grubby and washed-out looking. They hung languidly in the bluish evening air. The workmen tapped away at the trees and thrust ladders up into the ripe foliage, bringing down showers of leaves and a snow of pink and white blossom. Further on there was a cottage with two new Union Jacks thrust out from the windowsill. They hung down stiffly to attention. Against the mellow sunbleached texture of the stone their strident colours looked ridiculous and, because they were there on purpose to disturb the familiar contours, they gave a feeling of uneasiness. From there onwards all the little cottages were sprouting flags.

There was no one about to see them, and no very clear reason how they came to be there. Menacing each other across the road with their shrill colours they were like a flock of rare and fabulous birds which had alighted suddenly and without warning, clinging to chimney pots, windowsills and door posts. They were of many different sizes and shapes and attitudes corresponding partly to the income levels and patriotic fervor of their owners and partly to a certain capriciousness which they seemed to acquire on their own. Some of them, having been unfurled, had hitched themselves up again shyly over the poles. Others had a narrow strip of wood fastened along the extreme edge, so they were forced to suffer the maximum exposure. The large houses had older flags sewn together with pieces of silk with white painted poles and sometimes a gold tassle. The cottages all had new flags; the pieces of calico dyed with raw-looking colours. And when it rained they would run.

Outside one cottage an old woman was standing in a black dress with folded arms. She stood there most evenings, and I had passed her a hundred times without either of us taking any special notice of the other. But to-night she seemed to be standing there for a special purpose, as though expecting something to happen. As I passed her she smiled broadly at me. It was an indescribable smile that lay right across the road blocking my way and demanding an answer. I acknowledged it and hurried past, feeling guilty and uncomfortable and afraid that I might suddenly be called to play some part I had not rehearsed.

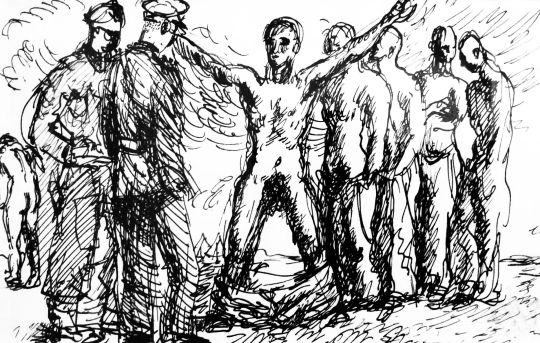

Keith Vaughan – Army Medical Inspection, 1942

On the dung-crusted door of a stable a V had been made with red, white and blue ribbon, and inside the V, hurriedly chalked as an afterthought, a red E. In the little window of the grocer’s was a newspaper cutting of the Prime Minister. It was stuck on the window with four large pieces of brown tape like a police notice. In the window that has bird seed and bottles of sauce was a gold frame with a reproduced oil-painting of two exceedingly mild and dignified lions, and in the bottom left hand corner the words ‘PEARS.’ In front there was a photograph of the Royal Family in sepia, with the word ‘CORONATION’ underneath and round circle of rust from a drawing pin. All the familiar and reliable things had suddenly disclosed a secret and unsuspected threat, though it would be impossible to say exactly what it was they threatened. But when the last house was passed and there were only fields and hedges and ditched frothing with tall white cow-parsley, there was a feeling of relief and reassurance.

Where the road swings sharply to the right before reaching the camp I crossed the little footbridge and sat down on the stile to smoke a cigarette. Between the layers of high lead-coloured cloud and the horizon, a narrow margin had been left in which the sun burned an enormous liquid orange disc. The air was like a thin violet fluid. In the further field was the boy who drives the tractor every morning past the camp. He was shooing some geese under a fence and into the straw-strewn yard if the cowhouse. He walked slowly forward towards the geese and at each step brought both arms up simultaneously above his head as though he were lifting something large that had suddenly lost all weight. His skin and clothes were soaked with the orange liquid from the sun. When the geese had gone he went out of sight behind the barn.

The near field was full of sheep. The full, woolly forms with sharp accents of light against the dark grass, the alternation between light-coloured sheep and dark ones, small and large, had that air of carefully-planned accident which one sometimes sees in paintings, but not often in nature. They glowed a deep gold colour like lumps of phosphorescent substance, and there were little pools of violet between their legs and in their ears. Two sheep had strayed down on to the steep bank of the ditch and were tearing ravenously at the thick, dark water-grass which met over their backs. They had pushed their way through gaps in the hedge and seemed to be expecting at any moment to be driven back. They were gulping as much as they could in the time, their eye wide with anxiety. Standing almost vertically faced downwards, they seemed to be in the most disadvantageous position both for eating and for coping with any sudden emergency that might arise.

The grass in the field was lighter in colour and had already been grazed down to a short turf like the thick pile on a carpet. Each sheep was eating with a sort of desperate concentration as though it had not seen grass for some time. They just kept their heads down and moved slowly forward, one foot at a time. But some, perhaps, because their necks had got stiff, had bent their front legs and were kneeling on their little fluffy knees with their black hoofs tucked up off the ground so as not to soil them and their backsides sticking absurdly into the air. The rams had hardly any wool and their skins had that grey, flatulent look that dead sheep have. They seemed inflated with eating and walked about painfully and awkwardly as though they were pregnant. They seemed just able to eat and transport their cumbersome genitals and excrete the little shiny damp balls of dung from time to time. That was a complete existence. The only sound was the crisp tearing of grass and an occasional low grunt and from the nearer sheep the muffled reverberations of some digestive process and blowing out of wind suddenly through the nostrils.

This, then, I thought, was the beginning of it all. This was perhaps the oldest thing on earth. Before cities and civilizations men had sat and watched sheep graze. In Canaan and Galilee and Salonica and Thrace, on the mountain slopes of Olympus and the Caucasus, on the plains of Hungary and the shores of the Black Sea, in Lombardy, Burgundy, Saxony, along all the routes where men had fought and followed, searching for a home and a pasture, sheep had grazed and men had watched them. Daphnis, Hyacinthus, Thyrsis, Corydon and the famous and anonymous shepherds of Galilee. And I tried to remember all that had gone on as an accompaniment to that watching, the immense architecture of hope that had been built up round sheep. The burnt offerings and symbols of love and innocence; the preyed-upon, the lost and the helplessly young. Sacrificed, worshipped, or just eaten, through mankind’s long adolescence sheep went on being sheep, somewhere in the background of every picture, greedy and silly and perpetually anxious. And each year the same disappointing story of promise and unfulfilment. The tiny wet thing with enormous legs first learning to kneel in the winter grass, as awkward and dangerous-looking as a child with a deck chair. The insolent butting at the udders. The entirely beautiful and unnecessary prancing of lambs, movement purely for the sake of movement, only to be forgotten in a few months in a complacent and woolly middle age.

Out of the north a flock of Fortresses came flying high. It was time for them to come and they crossed every night. The slowly-mounting noise focused the uneasiness in the air. Then I realized that tonight they would not be carrying bombs; the meaning of all the little flags suddenly became real. It was as if one had dreamt the noise: the approaching impersonal menace, the indiscriminate individual death and obliteration of cities, then at the climax of terror, walking, recognized the cause of the dream – after all, only airplanes flying. A sense of absolute security closed over every thing.

The sun has gone and over the horizon was left a stain of dried blood. The air was the colour of watery ink. At the camp the German bugler was blowing lights out. The sheep had finished eating and sat with folded feet, looking without concern on the first night of peace.