From Crafts Magazine Jan. 1979.

The farmhouse in which John Piper and his wife Myfanwy, the librettist, have lived since 1935 is couched in a thoroughly British landscape. This, the landscape of England and Wales, together with the art of the ‘‘French revolutionaries”’ — Braque, Picasso, Matisse, have been two main sources of inspiration in John Piper’s work, filtered through his own intensely personal, sometimes highly dramatic, romantic vision.

The involvement with craft techniques as a medium for artistic expression began early. A successful exhibition of his wood engravings in the twenties, “‘held at Heal’s of all places”? John Piper remembers, persuaded him to abandon his training as a solicitor in favour of study at the Royal College of Art and a career as an artist. In the thirties, John and Myfanwy Piper started Axis, a quarterly journal of contemporary art. This encouraged John Piper’s enduring interest in printmaking and in printing techniques. He made the rubber blocks from which to print the colour plates and, in 1938, produced his first aquatints as well as his first illustrated guidebook, The Shell Guide to Oxfordshire. Artists and designers quickly adopted his application of collage techniques to letterpress illustration.

Frequent exhibitions of abstract art in the twenties and thirties included John Piper’s paintings and the assemblages and collages in which he experimented with wood, paper, enamel and canvas materials. But abstract art before the war didn’t pay the rent. John Piper was in the same boat as Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and others, buffeted by the waves of the Establishment liner which cruised along with Frank Brangwyn and his kind at the helm. Articles and reviews supplemented the Pipers’ income and those by John Piper for Architectural Review demonstrated his ceaseless curiosity in topography and architecture and natural things; his eye for detail and structure showed itself in an appreciation of multifarious objects, which included sand-blasted pub mirrors, shop-front lettering and examples of nineteenth-century craftsmanship.

John Piper’s love of detailed observation has always been combined with a delight in colour. During conversation, his enthusiasms embraced Surrealism and eighteenth-century French enamels, Vuillard and Howard Hodgkin. When the subject of Minimal art came up, he seemed to seek solace in tangible, natural objects: sitting in the garden, he would trail his hand through pebbles on the ground, a diviner trawling in benign territory.

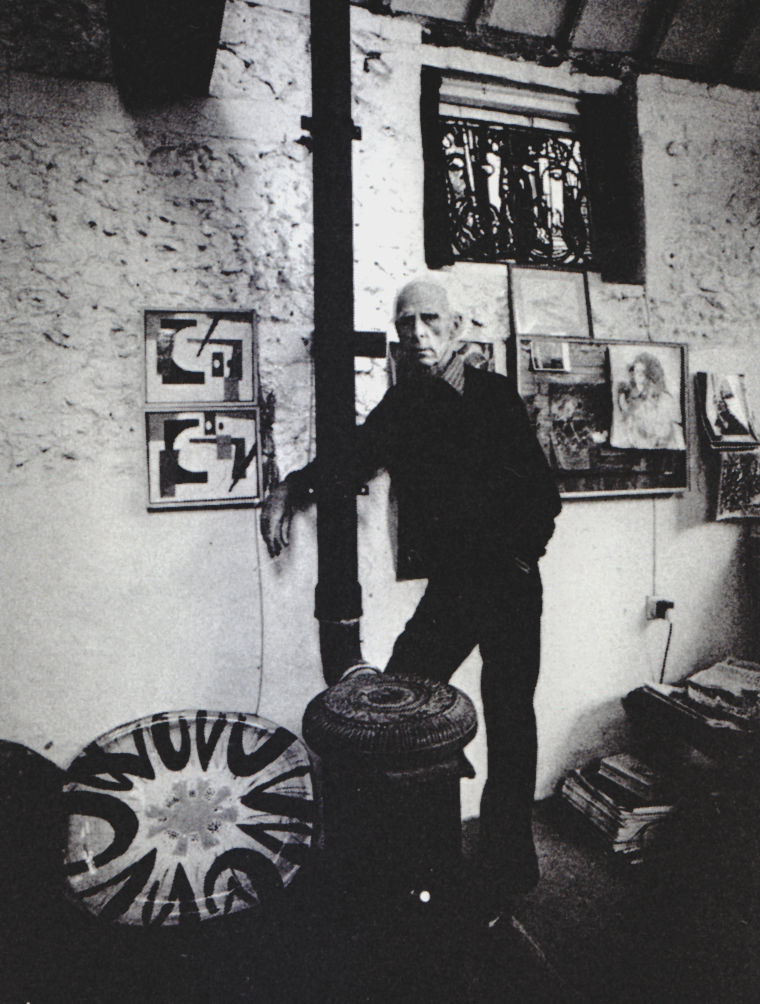

The preference for jewel-like colour and ornament, characteristic of John Piper’s semi-abstract topographical paintings, made natural his wish to design stained glass. ‘‘I wanted to do stained glass since I was fifteen’’, he said, ‘‘but the opportunity didn’t arise until I was fifty’’, John Betjeman introduced him to Patrick Reyntiens, then a twenty-three-year- old painter turned stained-glass maker, and a partnership began which continues still: Patrick Reyntiens, who also designs his own glass, has just begun the two-year task of making into stained glass John Piper’s fifty-five by thirty-six-foot cartoon for the chapel window at Robinson College, Cambridge. John Piper indicated the physical toll of designing such large-scale glass when, in a barn specially converted in the garden, the artist momentarily stood dwarfed by the huge space in which he worked ceaselessly for eighteen months to complete the 195-panel cartoon for Coventry Cathedral.

The styles of John Piper’s stained glass windows vary from the monumental Romanesque figurative style of the East windows in Oundle School chapel, his first major commission in 1954, to the abstraction of, for example, the windows in St Margaret’s, Westminster, those at Wolverhampton, or at Coventry. “The style of my work in any one medium always corresponds to the style of my painting at the time,” John Piper said. Nevertheless, a unity underlies the apparent eclecticism. As he once wrote: “Abstract painting in the hands of a sensitive painter has a classical appearance but a romantic soul.”

John Piper was reluctant to put into words what he felt about stained glass; but something of the necessary spiritual commitment to Christianity required to create the best stained glass for churches could be gathered from his remark that Picasso tried all media of artistic expression with the exception of stained glass ‘‘because he did not believe in the Church”’.

Patrick Reyntiens and John Piper are agreed on the importance of artists being involved in the creation of stained glass. John Piper’s book, Stained Glass, art or anti-art, serves as a manifesto on this theme. The gradual revival of stained glass making in Britain is due in great part to their collaboration, and John Piper welcomes the work of younger exponents, giving Brian Clark as an example. How does their collaboration work? “‘I am as the violinist is to a piece of music,” Patrick Reyntiens told me, “‘I am the interpreter, reconciling the declared emotional intent of the cartoon with the rhythm of line and the technical possibilities of stained glass.” The lead lines he inserts intuitively and he adapts the colours, which are more intense in glass than in the watercolour of the cartoon. In executing the numerous commissions over the last twenty five years, including windows in churches at Bristol, Liverpool, Swansea, Oxford and Eton College, Patrick Reyntiens has used a 6 the whole batterie de cuisine of technique. He mentions plating – leading two pieces of glass together to create a third colour, and aciding – removing the base colour to create two colours on one piece of glass which, combined with painting and staining can produce five or six colours on one piece of glass. Painting is done with glass paint, iron oxide in the form of glass dust, the technique which, Patrick Reyntiens explained, modifies the natural light and governs the sonority of the piece. Staining is done by means of a silver nitrate solution, while enamelling and transparent washes of fusible glass create further shadows and highlights. Each piece of glass is cut to within one thirty-secondth of an inch of the shapes in the freely-painted cartoon. But even technique at this virtuoso level “is subservient to vision”, Patrick Reyntiens believes.

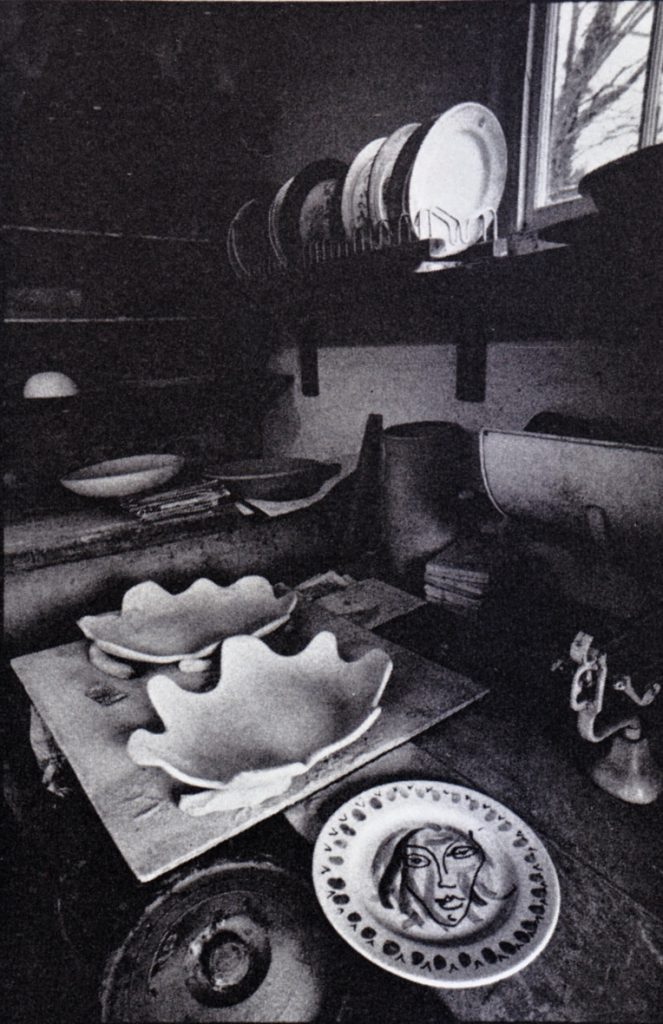

John Piper’s stained glass is painterly, like the French, where colour and light dominate and the lead lines merely hold the composition together. This is the antithesis of German design, where the colour is used to fill in a lead grid composition, typical of their graphic tradition, from Durer to Gunter Grass. This painterly approach also characterises his ceramics. Adverse critics of Picasso’s ceramics (for example Malcolm Haslam, reviewing Georges Ramié’s Picasso’s Ceramics in The Connoisseur, March 1976), let alone those by Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, would doubtless raise similar objections to the dishes, plaques and vases by John Piper, since he, too, primarily uses the ceramic form as a canvas. The composition of the decoration decides the form of the object, the antithesis of the craftsman’s approach. ‘‘Painters and sculptors make all the discoveries”’ John Piper said. “‘Craftsmen who make discoveries beyond the materials are artists’’.

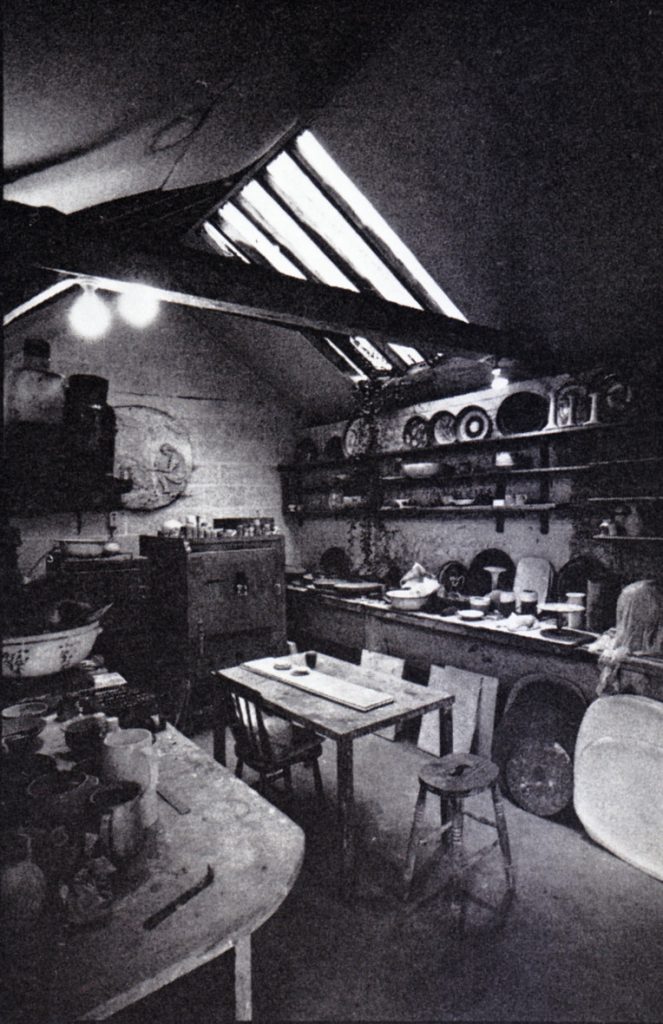

Since 1968, John Piper has learnt from the potter Geoffrey Eastop the techniques of hand-built pottery, making moulds, glazing and firing. Recently, John Piper has undertaken the whole process himself, although together they continue to refine the colours and techniques to achieve an ever more inventive painterly style. The use of the more heat-resistant T material earthenware clay is one such development. Its pallor provides a “primed canvas” without the need to use a slip, whilst its ‘‘tooth” (a roughness created by the grog mixture) provides a rougher texture, which enables John Piper to trail the glaze colour across the surface, breaking it as in brush work on canvas. The material, fired at 1150°C, is less inclined to buckle and crack, an advantage for the large-scale form of his pieces. Most of his ceramics are twice-fired, at 1040°C and then, glazed, at 1020°C, but recently, the technique of burning out wax has allowed for a more complex painted background and a third firing at 500°C.

The notable feature of John Piper’s ceramics is the depth of colour, not normally associated with earthenware. The problems of achieving this have inhibited many potters from working in earthenware. Often with underglaze decoration and majolica earthenware colour is not well integrated with form. John Piper achieves both textural depth and rich colour by applying colour and technique at several stages, starting with decorating in the dry state, then in biscuit, then adding glazes, then using wax resist methods to allow for further painting on top of the glazes and oxides. The resultant variety of texture and colour makes his imagery startlingly vivid, be it themes from nature, from mythology or from Poussin and allegorical figurative scenes. The excitement of strong painterly colour and composition is equally evident in John Piper’s tapestries, particularly in the High Altar reredos which hangs in Chichester Cathedral, woven by Pinton Freres near Aubusson. It exudes “‘the rocketing amongst the stars and comets” of a Miro and John Piper continues to be interested in the transposition of colour and curve of his paper cut-out and gouache cartoons into tapestry. (The same painterliness has led him to design vestments, and murals, mosaics and set designs, notably for Britten’s Death in Venice in 1972.) Archie Brennan’s Edinburgh Tapestry Company have recently completed John Piper’s tapestry for Sussex University chapel, and, in Namibia, local weavers are completing tapestries of the Tree in Eden, Zion and Heaven, which the artist hopes will find a home in Hereford Cathedral. ‘‘I have always accepted any commission I thought I could do,” John Piper said, although he has once or twice refused a commission for tapestry or stained glass where the building aroused in him strong antipathetic feelings.

For the future John Piper said: ‘“There is no new medium I want to try.”? When I admired his friend Alexander Calder’s mobile in the garden, nodding like a skeletal prehistoric bird, and asked about working in three dimensions, Mr Piper said that he wouldn’t do sculpture, just as he wouldn’t do jewellery, or, one surmised, anything to do with the primacy of form and plasticity.

But it is also because he is more concerned to show through his art his interpretation of what he experiences and sees in life than to show skill.

“Art has taught me everything I know’’, John Piper said, and this has influenced his attitude to crafts: “‘If crafts are to be any good, they must show that they have absorbed the teachings of the art of the time’’. This applies as much to a piece of thirteenth century glass, he says, as to work by Bernard Leach, which John Piper admires along with “‘some Lucie Rie and some Hans Coper’’, and which he feels certainly does reflect the art of his time, especially that of Ben Nicholson.

If artists can affect the way people see the world, perhaps John Piper’s particular interest in working also in craft media is not only because he loves experiment but because of the desire to share his discoveries with a wider audience.