Frans Masereel is above all a thinker. His art expresses ideas. He uses it to render thoughts and emotions which modern humanity has aroused in him. He is thus an enemy of Art for Art’s sake, of pure aesthetics. It is not only Beauty he pursues, but Truth. And he is an individualist: he hates standardization of human beings, of human thought. This attitude towards life he has admirably defended in his series of eighty-three woodcuts called: The Idea, its Birth, its Life, and its Death.

From this standpoint too, from his love of truth and justice, he attacks profiteers, industrial magnates, and warmongers, and on the other hand defends the submerged, the under-dogs, the weak, and the poor. This allies him to a certain extent with such artists as Kaethe Kollwitz and George Grosz, two other champions of the victims of our civilization.

Masereel, however, is more universal than Kaethe Kollwitz, who laments the distress of the labourer, or George Grosz, who castigates the bourgeois and militarists of Germany. Masereel deals with types of all classes and all countries, paints all the sufferings of humanity, not their social distress only. Even technically his work is distinguished from theirs: it looks, strangely enough, much more modern, although he uses quite primitive and well-known means. Kaethe Kollwitz’s art always suggests the technique of the German impressionists, especially that of Slevogt. His conception of the world resembles that of the great Walt Whitman, who, like himself, was a citizen of the world, rather than the child of his nation.

Masereel possesses two other characteristics: an astounding memory for all his experiences and impressions, and indefatigable industry. His whole, rich life is reflected in the works of this Fleming who was born in 1889 in Blankenbergh, where he spent the happy days of his youth — ‘playing much and learning little,’ as he himself says. For a short time he studied at Ghent and subsequently went to Germany, England, Tunis, and Geneva, in which latter town he remained during the war. From Geneva he protested, full of sorrow and indignation, together with his friends Romain Rolland, P. J. Jouve and René Arcos, against that indescribable massacre of mankind, publishing daily in the Genevan paper, La Feuille, satirical and anti-militaristic drawings and woodcuts.

For some years now he has been settled in Paris, high up on Montmartre, whence from his studio table he can overlook the sea of Paris houses. There he works quietly, day by day, and records with unremitting assiduity his experiences. As a result of this industry he has, apart from numerous drawings, oil-paintings and water-colours, already more than 1300 woodcuts to his credit, and he is only in his thirty-ninth year. I know no one who gives such an impression of richness and effortless spontaneity as does Masereel.

This boundless wealth of ideas surprises one, particularly in a series of sixteen cuts which he calls Memories of Home. In this series he often groups seven or eight little scenes round the principal subject, which elaborate it and strengthen the significance of the whole. In each of these pictures there are such a mass of notes, of contrasts which mutually enhance each other, that one never scans the pages of the book without discovering new details, hitherto overlooked.

This simultaneity of presentation has a dynamic force which only the cinematographic film can rival. Many of his woodcut series, especially his picture-novels, have terrific ‘speed’, which makes us turn from page to page almost breathless. This proves the great influence the cinema to which, incidentally, Masereel is passionately devoted — has had on his art. Under its influence were created his picture-novels, such as The Idea, The Passion of a Man, The Sun, My Book of Hours.

These books consist of a series of cuts without any letterpress, and are perhaps the greatest, certainly the most original, of Masereel’s creations. Superficially, these series, which he himself calls ‘Novels in Pictures’, remind us, by reason of their simple technique, of the primitive block-books of the fifteenth century and of the ‘Dance of Death’ series so popular during the sixteenth. Actually, however, they are entirely different. Instead of treating some religious theme, they describe the tearing speed of modern life and the pleasures and sufferings of modern city dwellers.

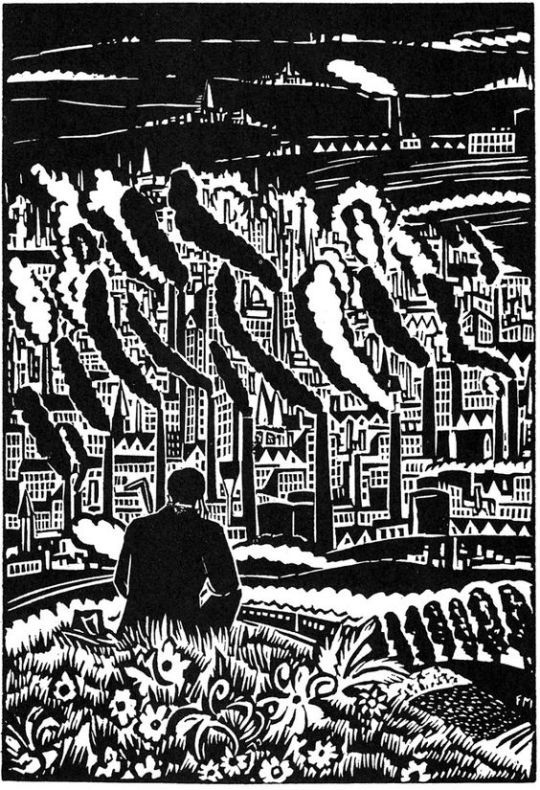

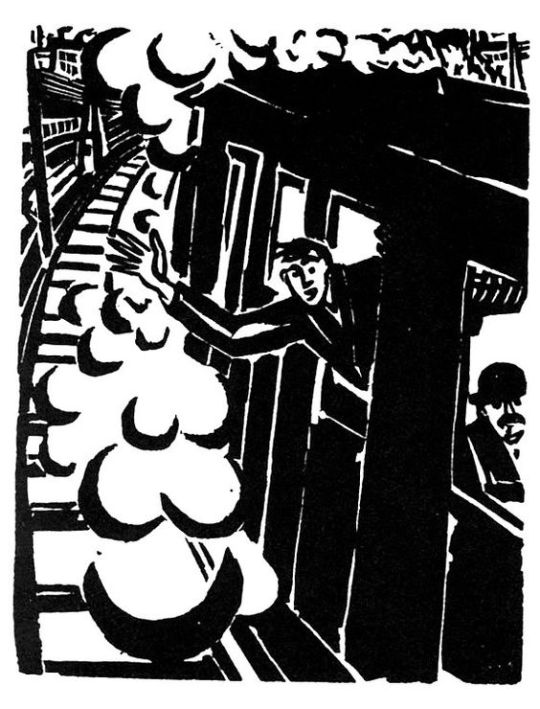

The Book of Hours is the most beautiful, the most varied, the most richly contrasted of Masereel’s works. This book was inscribed as a motto with Walt Whitman’s words: ‘Behold! I do not give lectures, or a little charity; When I give, I give myself.’ The hero of this novel, who resembles Masereel like a brother, arrives in a big modern city and finds himself thus suddenly surrounded by its roaring traffic. A stranger, he perambulates the streets with an observing eye; amazed, he looks at the motions of the machines; frightened, he sees the gaunt factory buildings and their smoking chimneys. Very touchingly expressed is the pure sensual joy of his first love adventures. His naive love, however, is derided by prostitutes, and he seeks refuge in the silence of a church. Then he leaves the city, laden with sorrow, and travels far and wide. Full of experience, he returns and would help his fellow creatures.

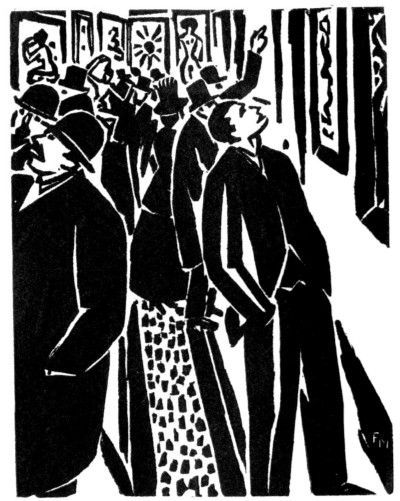

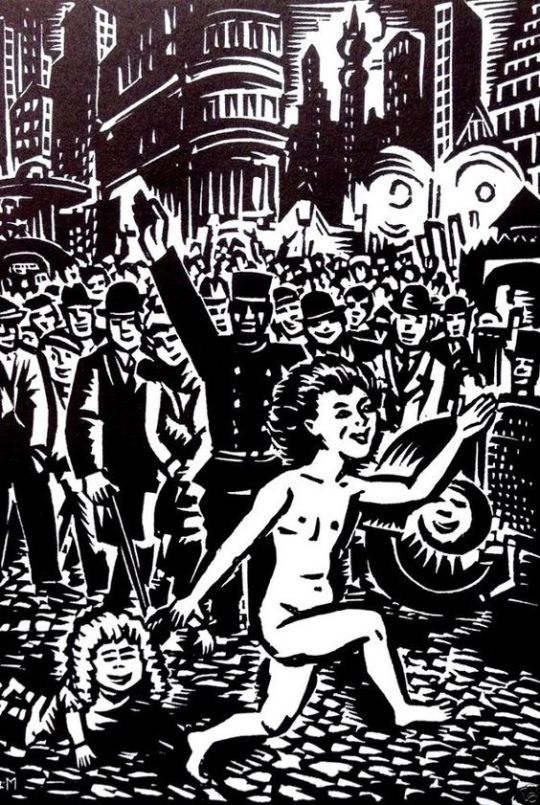

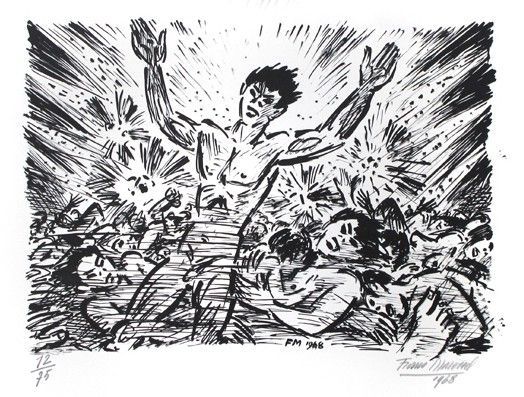

They, however, are too dull to understand him. In a true Flemish manner, Masereel describes the hero’s reaction against this dis- appointment. These cuts are full of life and movement, and powerfully suggest the Film. The hero is now seen making fun of everything, raves about, and does what he can to shock the Philistines. The end of this novel shows us Masereel in a new light; for he often loves to leave brutal reality in order to soften things in the air of poetic imagination. So here: the hero of the Book of Hour: leaves his fellows, seeks the solitude of a wood, and dies alone. Now at last freed from his body he stamps upon his all too human heart that has brought him so much sorrow, and wanders free through the limitless space of the Universe.

The woodcuts of this Book of Hours are, like most of Masereel’s, in black and white, with large spaces. This gives them a kind of monumental power. But as this style is too circumscribed in its possibilities, and inclined to clumsiness, and invites, on account of its apparent easiness, cheap effects, Masereel combines it with a discreet play of white and black lines.

He, however, never makes the mistake of producing tone by complicated cross-hatching, which confuses the lines: with Masereel each line remains clearly visible and retains its own character. The masterly manner in which he is able to render the most varied emotions in spite of his simple and primitive technique can readily be seen in the examples here reproduced.

Amongst these ‘The Lovers’ is an excellent illustration of another quality of Masereel’s genius: the originality of his inventions. How many ‘lovers’ have we not seen since the woodcut was invented! No other woodcutter, however, has treated this hackneyed theme in a manner at once so original and so true. And Masereel, too, sees his pictures from ever-varying optical viewpoints.

A few words must here be added concerning Masereel’s book- illustrations. For technical reasons his woodcuts are generally not very suitable for this purpose. It is impossible to produce an absolute harmony between Masereel’s cuts and the letterpress, since even the blackest and heaviest type-face produces a grey surface; Masereel’s woodcuts, however, are never grey in effect: there is always a self-contained harmony of black and white masses.

The best results, typographically speaking, were obtained by Masereel himself, with the illustrations for Les Pâques à New York. In this book, which was set up under the artist’s strict direction, large black type was used — the letterpress widely spaced, and the type-face of the page empanelled with a thick black rule. In this manner a balance was achieved between the letterpress and the illustrations. In his Owlglass (Ulenspiegel, published by Kurt Wolff), too, the result was satisfactory because it was printed in old German Black-letter. None of these illustrations, however, belongs to Masereel’s masterpieces, because his personality is too strong to be forced into the mould of another’s.

It took a long time before the work of this great artist received the attention it deserves. Now, however, his fame is spreading. In Germany and France enormous editions of his picture-novels are sold out; in America the circle of his admirers is steadily growing; in Russia his woodcuts are seen on the Government poster hoardings. And now his name is mentioned in the same breath with Callot’s, Daumier’s, and Van Gogh’s.

By Edmund Bucher – From Volume II — The Woodcut: An Annual by Herbert Furst.