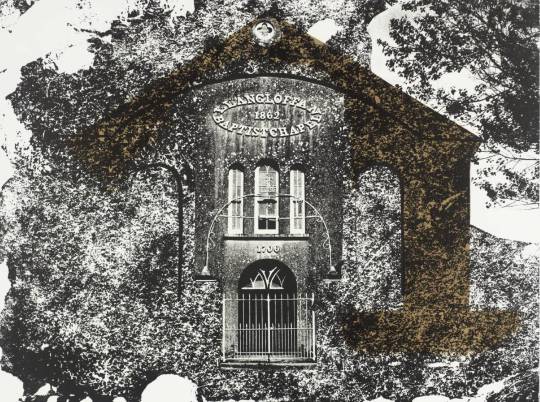

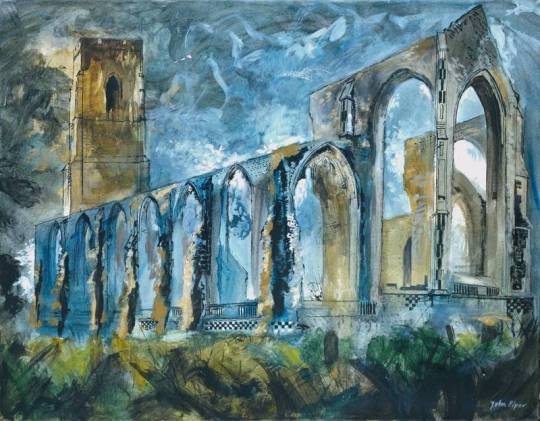

John Piper – Fawley V, 1989.

Text: Fawley I to X by David Fraser Jenkins

There is no rule to be observed that an artist’s work has to become looser as he gets older. It is easy to think of some remarkable cases where this happened, but this is because the late works of more usual careers with comparatively little change are less prominent. John Piper’s latest exhibition shows paintings of a startling freedom, but in his whole long career he has always swung between detailed and exuberant manners, whether the detail is the precise outline of an abstract painting or of a window at Windsor Castle, or whether the exuberance is of a collage of marbled papers that became one of his pre-war landscapes or of the whirls and blotches that decorate his pottery of the last twenty years. He has not been able recently to travel to his subject, and has fallen back onto something that he has saved for years, the garden of his own house.

John Piper – Fawley VII, 1989.

Piper is one of the few modern figurative artists who has never painted, or even photographed, a view of his own studio, since he has not wanted to tell people about himself, or idolise his own art. He may in effect reveal much, but only by inference. Until recently he has rarely painted even the valley and farmhouse where he lives. During the 19805 more paintings of his house and garden were exhibited, and for the summer of last year he made a whole exhibition of paintings of blossoms and of the garden. ‘Pear Tree and X/all’ from that exhibition almost overlaps with the new paintings, as the twisted tree seemed to cavort unrealistically in some black space of its own, almost dancing with liveliness.

The paintings now shown by Piper are amongst the best of his whole career, for his painterly skills are more evident as the given structures of the subject dissolve, and rarely has his work seemed so very personal and without outside occasion.

In the last few years there have been in London several gardening exhibitions, mostly historical, presumably in sympathy with the more conservative taste that has become noticeable. Gardens however are not only for retreat or withdrawal. They are also the battlefield of nature against cultivation, and the life and death not only of all plants with the seasons but between competing growths, some of which can survive by fertilisation and seeding.

John Piper – Fawley X, 1989.

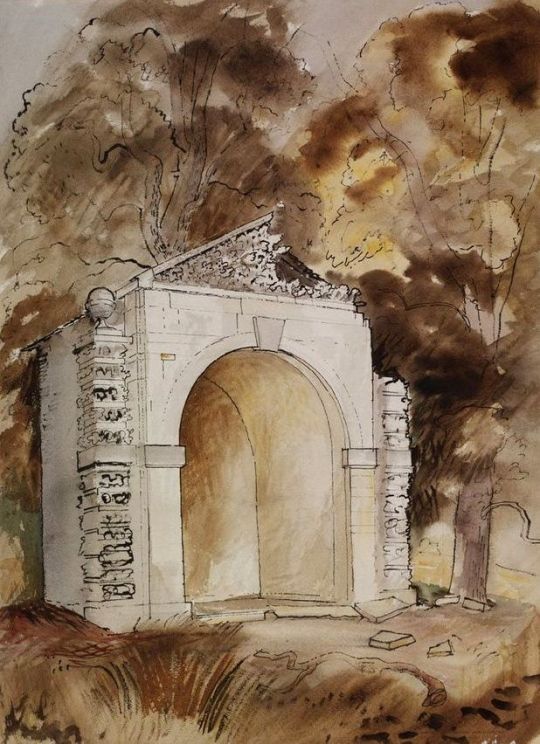

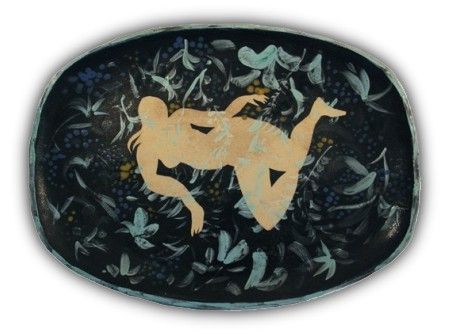

Piper has always avoided inventing figures in his work. The splendid Kings of Oundle College windows are translations of romanesque carvings and not his own figure studies. The figures in his photographs are obscured, either by fragmentation or by covering with foliage like a ’Wild Man’. He has admired the ’foliate heads’ of English gothic sculpture, and has two such heads in his studio, where he often places alongside them the gigantic drooping heads of‘sunflowers.

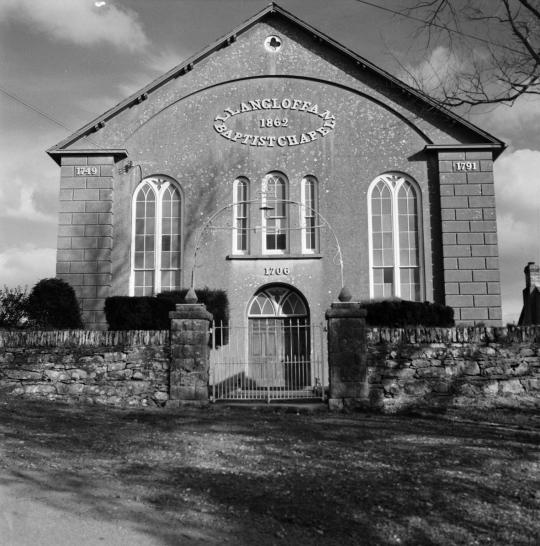

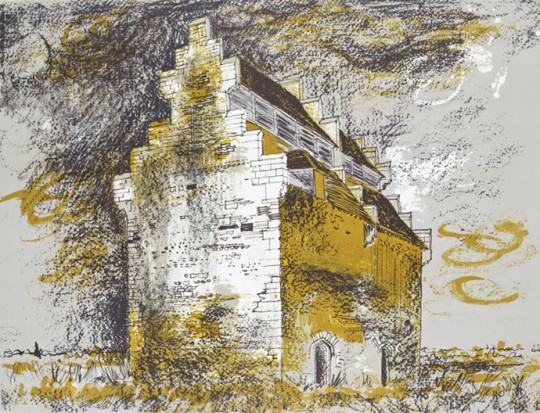

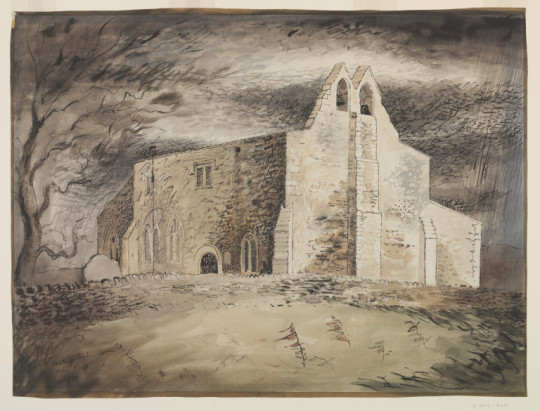

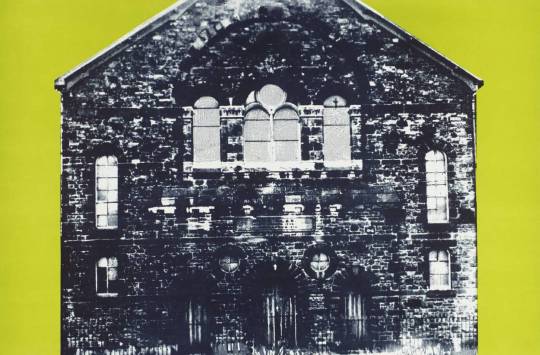

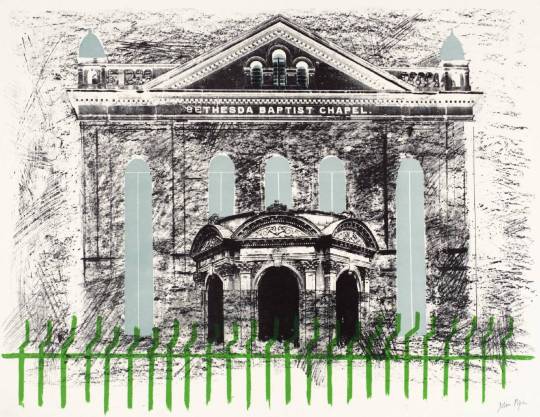

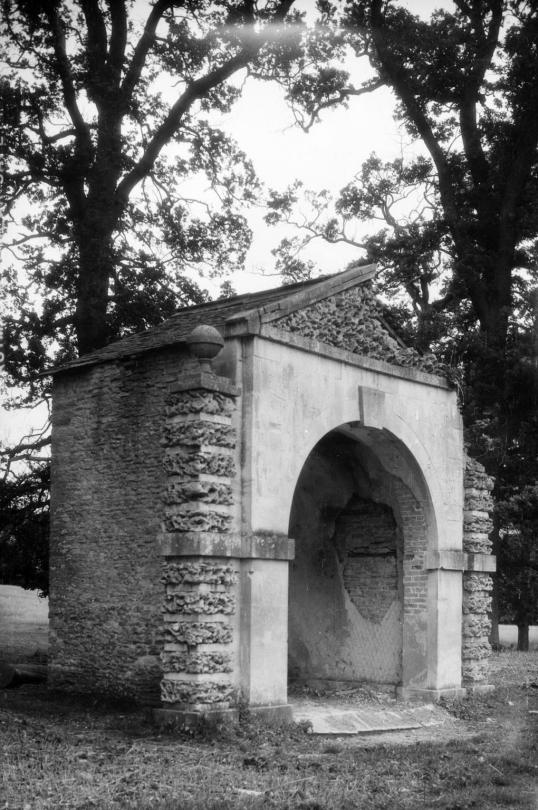

A favourite of his photographs is the ’lived Figure’ of Wotton, his title turning the name of the plant into a verb. It is only an extension of this where these new paintings are themselves ivied, or convolvolussed, herbascioussed and chrysanthemums. If the garden could be pruned, the statues, walls and paths would appear; but Piper has always fought against tidying up. This is an attitude of mind that opposed the clearing of buddleia from abbey walls by the Ministry of Works, and is also part of the sheer generosity of character that made those copious screenprints of well known and out of the way buildings, in extremes of light.

It is difficult to be certain in these new paintings whether the plants have covered the foreground or have somehow taken over the whole vision of the artist, leaving only a few spots of clear light. The overhanging eyebrows which looked so spooky in Phil Starling’s photograph of Piper on the cover of The Independent Magazine (10 December 1988) might have forced the vision back into the mind. These paintings were all begun with a wide brushed coating of white, mixed with sand to give a rough surface.

John Piper – Fawley VIII, 1989.

The prominent blacks almost obscure the light, left shining through in places like the opening of a cave. The flowers and leaves are in front of this blackness, things not quite known that are alive in this darkest part of the garden. Piper’s ordering of the colours still follows the discipline of his abstract paintings, which were themselves partly the result of his study of medieval stained glass painting.

The intense reds and blues of such windows, used sparingly but decisively within the design of heavy black outlines and borders, were models for his abstraction and have remained so most clearly whenever his painting has become less realistic. This harmony of colour is noticeable now more than ever, a harmony like Venetian and French painting that is a kind of eloquence based on patterns of contrast, and which gives the paintings a feeling of large scale.

John Piper – Fawley III, 1989.

John Piper’s studio with flower paintings on the easel.